Researchers in Germany have recently unveiled ultra-resistant materials designed to withstand the extreme conditions inside future fusion reactors and protect the inner surface that directly faces the superheated plasma.

Led by a team of scientists at the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT) and their colleagues from the laser-fusion company Focused Energy, the project, known as DINERWA, focused on designing a more durable version of fusion reactors’ so-called first wall.

The first wall is the innermost solid surface of a fusion reactor’s vacuum chamber, which directly faces the plasma. It acts as a critical barrier and protects the rest of the reactor’s structure from the extreme conditions of the plasma.

“One of the greatest technological challenges for future power plants is the ‘first wall’,” Carsten Bonnekoh, PhD, a researcher at KIT’s Institute of Applied Materials (IAM), pointed out.

Built for extreme heat

The idea of igniting a star on Earth is fundamental to fusion energy, which is a field widely seen as one of the most promising paths toward clean and virtually inexhaustible power.

Nevertheless, reaching that goal requires every part of a fusion reactor to endure conditions far beyond those found in conventional power plants and to maintain that resilience for long periods of time.

Bonnekoh emphasized that the first wall should be able to protect the reactor’s interior from temperatures hotter than the sun. “It shields the hot plasma and must withstand enormous temperatures and neutron radiation,” he added.

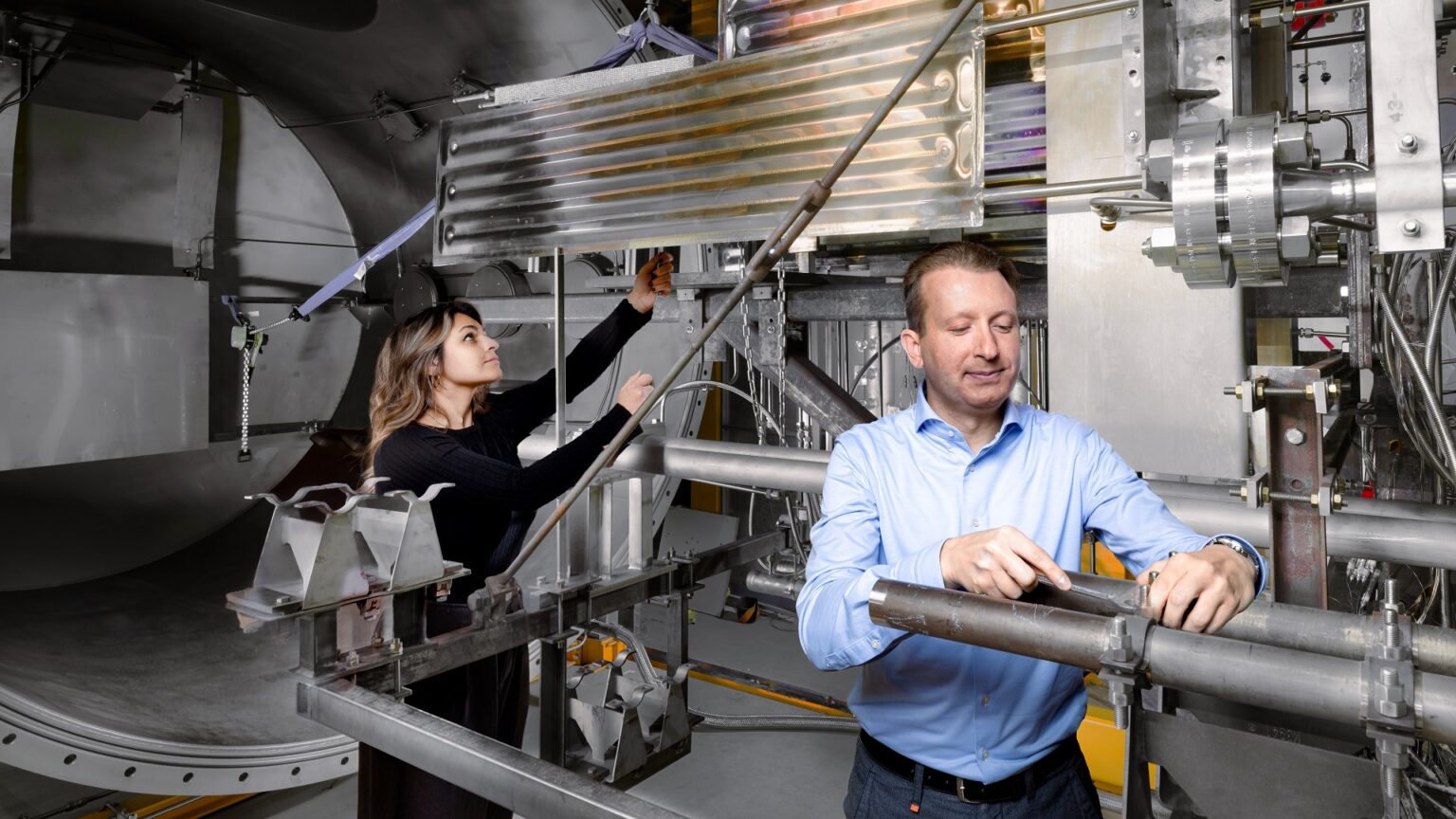

Components for fusion power plants are tested at KIT using the HELOKA research infrastructure (Helium Loop Karlsruhe).

Components for fusion power plants are tested at KIT using the HELOKA research infrastructure (Helium Loop Karlsruhe).

Credit: Amadeus Bramsiepe, KIT

To tackle the challenge, the KIT team came up with a new generation of structural and functional materials, which they claim are capable of resisting thermal loads, radiation damage and mechanical stress above the limits of conventional metals.

These included oxide-dispersion-strengthened (ODS) steels and copper alloys, nanostructured tungsten and emerging high-entropy alloys. Each material was created at the microscopic level to remain stable even when exposed to extreme heat and intense neutron flux.

“We aim to significantly extend the first wall’s lifespan, ensure its industrial manufacturability, and take an important step toward making industrial fusion power plants economically viable,” Wolfgang Theobald, PhD, a lead scientist at Focused Energy and DINERWA project manager, revealed.

Protecting reactor walls

The project, however, is not limited to new materials. The team is also developing advanced manufacturing and joining methods needed to assemble the materials into complex reactor-scale modules.

“We want to demonstrate that the materials not only perform well in the lab but also remain stable under real operational loads,” Bonnekoh concluded in a press release. “This will lay the foundation for using today’s experimental materials in actual power plant components in the future.”

According to the researchers, much of the development is taking place at KIT’s HELOKA (Helium Loop Karlsruhe) facility, one of the world’s leading test stands for high-heat-flux conditions.

At the facility, the scientists expose prototype components made from the newly engineered materials to heat loads as well as mechanical stresses similar to those expected inside future fusion reactors.

These tests should help the team understand not only how the materials behave under pressure, but also how long they can survive before requiring maintenance or replacement.

The initiative was backed by Germany’s Federal Ministry of Research, Technology and Space (BMFTR), which provided USD 12.7 million (EUR 11 million) in funding to accelerate progress toward usable reactor components.