US President Donald Trump may be a champion of making America great. When it comes to other countries, however, the proudly America Firster is interested in how they trade with the US, stopping conflicts, and having their leaders publicly back his flagship initiatives.

He has been emphatically uninterested in committing American resources to improving the governance and humanitarian record of foreign countries.

“We are getting out of the nation‑building business, and instead focusing on creating stability in the world,” Trump said in a major foreign policy address during his 2016 campaign, marking a shift from predecessors who tried to export American values to developing states. “Our foreign policy will always put the interests of the American people, and American security, above all else.”

He returned to the theme in May during a visit to the Middle East, long a crucible of American adventures in state-building. Presenting his vision for the region in Riyadh, Trump said that “great transformation” of prosperous Gulf countries “has not come from Western interventionists… giving you lectures on how to live or how to govern your own affairs. No, the gleaming marvels of Riyadh and Abu Dhabi were not created by the so-called ‘nation-builders,’ ‘neo-cons,’ or ‘liberal non-profits,’ like those who spent trillions failing to develop Kabul and Baghdad, so many other cities.”

“In the end, the so-called ‘nation-builders’ wrecked far more nations than they built — and the interventionists were intervening in complex societies that they did not even understand themselves,” he thundered.

In one place, however, Trump seems to be the one heartily intervening. He is committing American treasure to a project in Gaza that increasingly looks like the very thing the US president has so vociferously opposed.

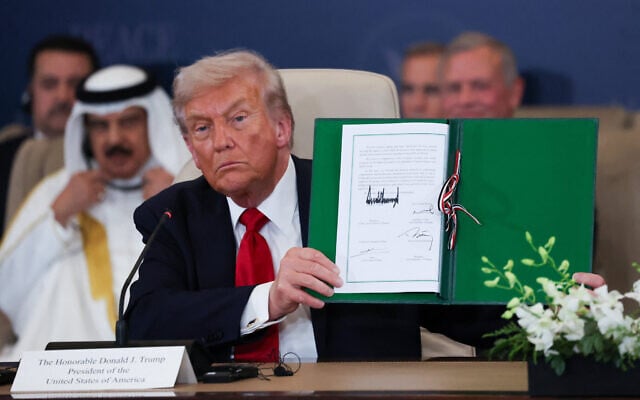

US President Donald Trump poses with a signed agreement at a world leaders’ summit on ending the Gaza war, in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt, October 13, 2025. (Suzanne Plunkett, Pool Photo via AP)

Trump cajoled, pushed, threatened and enticed pro-Western leaders in the Middle East and beyond to back his 20-point vision for a ceasefire in Gaza and rebuilding of the Strip after two years of war between Israel and Hamas.

With the first phase of that plan nearing completion, the US and its allies are now shifting their focus to the next phase, the creation of a prosperous, demilitarized Gaza free of Hamas rule.

But to make that vision a reality, Trump looks to be following a path with pertinent similarities to those taken by the US in Iraq and Afghanistan. In both of those cases, American missions to foster the trappings of modern, competent statehood, from security and citizen services to US-friendly free-market economics, ultimately fell apart, now remembered as resource-wasting quagmires.

LISTEN to the Lazar Focus:

In recent weeks, reports and leaks out of the White House have signaled that the US is willing to at least consider taking an active role in building Gaza back up. Trump and other officials have hinted at the prospect of more intense US involvement in the project than previously speculated.

“Maybe this is going to be the greatest deal of them all,” Trump said while wrapping up a speech to world leaders last month at a summit in Sharm El-Sheikh to rally support for the Gaza plan. “Not just nation-building.”

Things fall apart

On the debate stage during his 2000 run for the White House, George W. Bush said that he “would be very careful about using our troops as nation builders.”

Bush was making his pitch after a decade that saw American military interventions in Haiti and the Balkans in which US troops were used to impose order and promote international efforts to create new governing structures.

The September 11, 2001, attacks on New York and Washington changed his approach entirely.

Bush ordered the invasion of Taliban-held Afghanistan, followed by Saddam Hussein’s Iraq. Those short and successful conventional military campaigns quickly gave way to far more ambitious programs to bring democracy to the newly liberated countries.

The effort became the focus of US military and foreign policy. The Department of Defense in 2005 made stability operations one of the US military’s “core missions.” The State Department stood up the new Office of the Coordinator for Stabilization and Reconstruction, while the UN created the Peacebuilding Commission to oversee such missions.

In this January 28, 2012, file photo, US soldiers, part of the NATO-led International Security Assistance Force (ISAF), patrol west of Kabul, Afghanistan. (AP/Hoshang Hashimi, File)

The US spent over $140 billion in reconstruction in Afghanistan, seeking to build a centralized democratic government in a country dominated by tribal alliances and weak central governance. The effort eventually morphed into a series of NATO missions, with some 51 contributing countries helping prop up Afghan forces. NATO Provincial Reconstruction Teams secured rebuilding efforts and helped locals “establish good governance and the rule of law, as well as…promote human rights.”

However, corruption was rampant, and billions of dollars of aid went into the pockets of warlords and corrupt ministers. With Afghan security forces largely ineffective and the public losing faith in the US-backed government, a Taliban insurgency spread, leading to a troop surge that peaked in 2011 with 100,000 US soldiers in the country.

When those troops began to leave, the Taliban steadily asserted its control over greater swathes of the country.

Taliban fighters atop Humvees prepare before parading along a road to celebrate after the US pulled all its troops out of Afghanistan, in Kandahar on September 1, 2021, following the Taliban’s military takeover of the country. (Javed Tanveer/AFP)

Everything fell apart in 2021. With US forces scheduled to leave, the Taliban took over rural areas, then provincial capitals, and finally entered Kabul in August 2021.

Today, the Taliban governs the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, and ranks at the bottom of The Economist’s Democracy Index, two spots below North Korea.

In Iraq, Bush said that his goal was a country that is “peaceful, united, stable and secure, well integrated into the international community, and a full partner in the global war on terrorism.”

US Army 1st Battalion, 24th Infantry Regiment Lt. Col. Erik Kurilla, right, and his soldiers pursue an insurgent sniper after two soldiers were shot and wounded, one in the hand and one in the leg, in Mosul, Iraq, Feb. 10, 2005 (AP Photo/Jim MacMillan, File)

But a failure to understand the scale of the challenges facing the US doomed efforts in the years after the fall of Saddam’s regime. “The US occupation of Iraq was marked by a series of unanticipated challenges and hastily improvised responses,” wrote the authors of a Rand study.

Initially focused on military gains, the US eventually shifted to winning Iraqis hearts and minds while trying to keep insurgents in check, all of which came at a significant cost.

In this Oct. 11, 2007 file photo, then-U.S. Commander in Iraq, Gen. David Petraeus, left, talks with Iraqi Assal Jassim during his visit to the village of Jadihah northeast of Baghdad, Iraq. (AP Photo/Khalid Mohammed, File)

In the first decade of the war, the US spent around $53 billion on reconstruction alone. By the time US soldiers pulled out in 2011, 4,500 Americans and hundreds of thousands of Iraqis had been killed.

Despite the massive investment, America’s nation-building campaign in Iraq could not overcome Iranian support for Shia insurgents and political parties, a lack of democratic tradition, a political culture marked by authoritarian rule and legitimized violence, and a weak middle class.

Iraq’s Prime Minister Mohammed Shia al-Sudani (C) delivers a speech during a campaign rally for the Reconstruction and Development Coalition ahead of the country’s parliamentary elections in Baghdad on November 7, 2025. (AHMAD AL-RUBAYE / AFP)

Nonetheless, the country has managed to maintain elements of constitutional governance that make it one of the more democratic countries in the Arab world.

“Iraq holds regular, competitive elections, and the country’s various partisan, religious and ethnic groups generally enjoy representation in the political system,” Freedom House wrote last year. “However, democratic governance is impeded in practice by corruption, militias operating outside the bounds of the law and the weakness of formal institutions.”

During the brief interregnum that preceded the US sending troops back to Iraq following the rise of the Islamic State, the Rand Corporation labeled the war and its outcome “at best a tenuous, qualified success,” which was still more than could be said for Afghanistan.

“Iraq is not in open conflict with its neighbors, but terrorism and limited insurgency continue across the country,” read the 2013 study. “Iraq is united under a constitutional government for now.”

Stabilization or civic seeds?

There are certainly key differences between US efforts in the Middle East after 9/11 and Trump’s fledgling multi-national initiative to transform the Gaza Strip.

While Washington emphasized fostering democratic values and creating public institutions in Iraq and Afghanistan, this has not been mentioned thus far as a central feature of US plans in Gaza.

A Taliban fighter stands guard as women wait to receive food rations distributed by a humanitarian aid group in Kabul, Afghanistan, May 23, 2023. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi)

Palestinian statehood is mentioned as an eventual goal of Trump’s plan for Gaza, but the scheme’s more concrete facets, such as transferring governing power to technocrats and training police, are aimed at stability rather than civic participation.

“This isn’t nation building, which I really think people use on my end to discredit the work that has to be done,” said John Spencer, chair of Urban Warfare Studies at the Modern War Institute in the prestigious US military academy West Point.

“I actually don’t think you’ll see one governance in Gaza anytime soon,” he predicted. “You’ll see the stable zones with governance, local governance, while other people take on this massive challenge of Palestinian Authority reform and all of the future of that.”

“Nobody’s building a nation in Gaza,” Spencer maintained. “They’re building bubbles of stable zones.”

Nonetheless, elements of the emerging Gaza project echo the US experience in Iraq and Afghanistan.

In a 2006 address, Bush laid out the three main elements of his Iraq strategy: “On the political side, we are helping Iraqis build a strong democracy, so that old resentments will be eased, and the insurgency marginalized. On the economic side, we are continuing reconstruction efforts and helping Iraqis build a modern economy that will give all its citizens a stake in a free and peaceful Iraq. And on the security side, we are striking terrorist targets and training the Iraqi security forces.”

US Vice President JD Vance speaks to the media as US Special Envoy to the Middle East Steve Witkoff and White House adviser Jared Kushner stand next to him, at the Civil-Military Coordination Center in Kiryat Gat, Israel, October 21, 2025. (AP Photo/Francisco Seco)

Economic development and building local security forces are very much a part of the US vision in Gaza.

Trump’s 20-point plan places a significant emphasis on the economic development of the Strip: “A Trump economic development plan to rebuild and energize Gaza will be created by convening a panel of experts who have helped birth some of the thriving modern miracle cities in the Middle East.”

“Many thoughtful investment proposals and exciting development ideas have been crafted by well-meaning international groups,” Trump’s plan continues, “and will be considered to synthesize the security and governance frameworks to attract and facilitate these investments that will create jobs, opportunity, and hope for the future of Gaza.”

On the security side, according to the plan, a temporary International Stabilization Force — not to be confused with the International Security Assistance Force in Afghanistan — “will train and provide support to vetted Palestinian police forces in Gaza, and will consult with Jordan and Egypt, who have extensive experience in this field. This force will be the long-term internal security solution.”

A photograph shows a displacement camp in Gaza City on November 14, 2025. (Omar AL-QATTAA / AFP)

There are also signs that the US could be involved in building Gaza’s governing bodies. According to Israel Hayom, one of the teams at the Civil-Military Coordination Center (CMCC) in Kiryat Gat is “thinking through how to build Gaza’s civilian institutions so that the next generation of Gazans will be peaceful.”

During a visit to the CMCC on Wednesday, The Times of Israel observed a meeting by the Civil Governance team with dozens of participants.

Officials involved with the CMCC told The New York Times that “scenes of American soldiers tossing around ideas for how to rebuild the devastated Gaza Strip evoke uncomfortable memories of other US-led attempts at reconstruction in Iraq and Afghanistan.”

The US investment in those initiatives could be limited if international partners agree to shoulder much of the burden.

But the American involvement could well be far larger than anticipated. In both Iraq and Afghanistan, the US had dozens of partners, but was still the main contributor.

A PowerPoint presentation at an October symposium at the CMCC “detail[ed] plans for significant US involvement in Gaza even beyond security matters, including overseeing economic reconstruction,” Politico reported recently.

Visiting US Secretary of State Marco Rubio meets with US troops at the Civil-Military Coordination Center in Kiryat Gat on October 24, 2025 (Marco Rubio via X)

Palestinian security forces will need “long-term US and international support,” according to another document from the symposium. “Security and police forces may need outside funding and advising for decades.”

Lessons from past experiments

The US is already devoting significant resources and attention to the future of Gaza, including during the recent federal shutdown period when Washington’s own government stopped functioning.

Aside from the air train of top administration officials visiting Israel since the ceasefire, including Trump and his Vice President JD Vance, there has also been a steady influx of Pentagon brass with the establishment of the CMCC.

US Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Gen. Dan Caine was in Israel to fly over Gaza and visit the CMCC, as was CENTCOM commander Adm. Brad Cooper. Lt. Gen. Patrick Frank, commander of US Army Central and the US pointman at the CMCC, is living in Kiryat Gat, as are other American generals.

Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu visits the Civil-Military Coordination Center in Kiryat Gat on October 29, 2025, meeting IDF Maj. Gen. Yaki Dolf (left) and US Lt. Gen. Patrick Frank (right). (Maayan Toaf/GPO)

Some of the people Trump has brought in to implement his outline were deeply involved in the past US nation-building efforts in the Middle East. Chief among them is former British prime minister Tony Blair, who took the United Kingdom into the US-led invasion and reconstruction of Iraq, and now has taken on a leading role in overseeing the postwar administration and reconstruction of the Strip.

Even if Trump stops short of a full nation-building program in Gaza, there are still relevant lessons that emerge from the costly US experiments in Iraq and Afghanistan.

An ostensibly time-bound and limited initial investment can balloon into a long and expensive commitment. Competent local security forces are notoriously difficult to create, especially when foreign peacekeepers head home. Rival countries will be trying to undermine what the US is doing.

“Britain and France both tried it,” warned historian and former envoy to Washington Michael Oren of Middle East nation-building efforts. “They lost their nerve and they ran away. America is liable to do the same thing.”