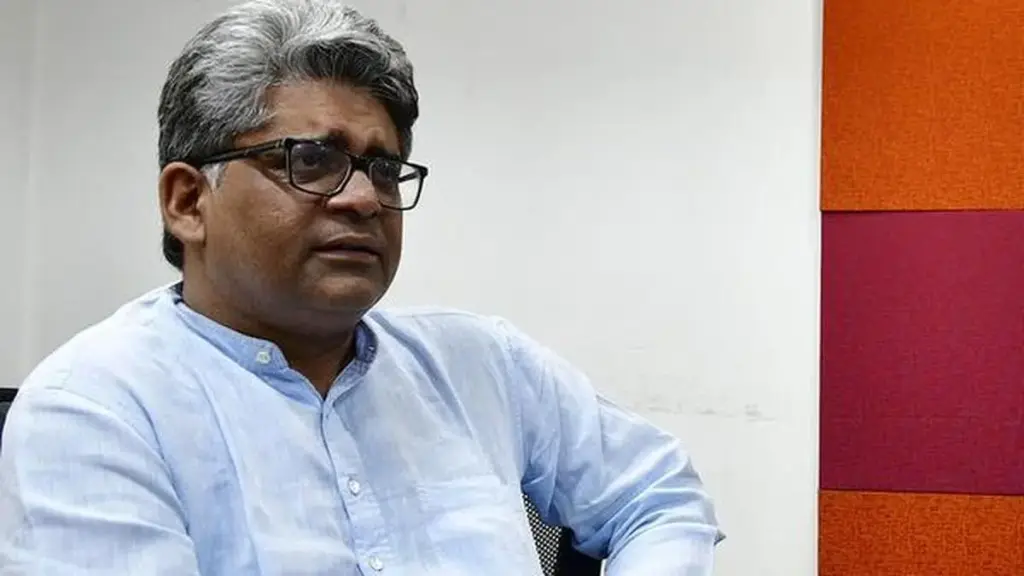

Economist Rathin Roy argues that India’s climate transition is constrained by a consumer-heavy state, a rent-seeking private sector, and an international finance regime stacked against the Global South.

| Photo Credit: THE HINDU

On November 22, 2025, COP30 came to a close in Belém, Brazil, with no fanfare. A much-touted “implementation COP” was derailed by a push—primarily by the European Union—for a fossil fuel phaseout that lacked consensus among many developing countries due to reasons such as a lack of clarity, finance, and equity. Governments from Arab countries opposed phaseout language, as they often do, citing impacts on their economies. Negotiations on a just transition and adaptation finance resulted in a weak outcome as well.

Frontline spoke to economist Rathin Roy about why climate negotiations on finance continue to stall, low-productivity coal and clean energy manufacturing in India, unsustainable consumption and the Brundtland Commission and more.

Excerpts below:

COP30 has ended, and much like earlier COPs, negotiations on climate finance did not see much progress. What is your assessment of developing countries’ needs for climate finance and rich countries’ reluctance to meet these demands?

There are different demands for climate finance from developing countries. Once you abandon the principle of common but differentiated responsibility, there is no question of climate finance being owed by developed countries to developing countries. Then it becomes a question of climate finance moving from rich countries to poor countries in the mutual interest of the rich and the poor. This was best captured by Mia Mottley’s [the Prime Minister of Barbados] Bridgetown Initiative, which posits three kinds of climate finance. One is humanitarian, which is that the loss and damage caused by climate change to vulnerable countries such as the Caribbean or Pacific island nations will be devastating enough to qualify as humanitarian disasters. And this is where we should focus on grant finance. Because the appetite for the world to provide grant finance is limited. And I oppose this deification of climate finance outside of loss and damage.

The second kind is concessional loan finance for low-income countries [such as those in Africa] to adapt or mitigate climate change. With countries such as India, Brazil, or Turkey, we have not sought grant or concessional finance because we understand that it will never happen due to the asymmetric balance of power, which defeats economic logic. It is true of climate finance as with any finance. Most old people in the world live in rich countries. They don’t contribute in terms of income, but they make a lot of money from accumulated historical wealth. The young people, on the other hand, live in poor countries. Logically, you should take young people to where the wealth is because this would create prosperity for the old and young. But rich countries don’t like people who live in poor countries.

They don’t want people who are ethnically and culturally different to come and work in geographies where the wealth is. Then the option is that you take wealth and put it into geographies where poor people are, so they can work on it. Logically, capital should flow from rich to poor geographies, including private finance. But rich countries are not able to do this due to the existence of a risk premium. A country’s risk rating defines the risk premium. I call this, “Don’t like your face premium”.

Per capita GDP is a key factor in assessing a country’s sovereign credit rating. So, we have lost the risk game already. There are also other problems, such as real institutional risk. If there is any negotiating to be done by large developing countries such as India and Brazil on an international stage, and if the world believes that climate investments are indeed necessary, then we have to find a way to give alternative risk ratings to investments that are globally necessary, such as climate investments. The ask is a fairer rating that recognises climate investments as a global public good and makes finance for such investments available at scale and affordable rates.

Coming to domestic sources of climate finance, what do you think are the best uses of public finance, and where do you see private finance playing a role?

There are two points here. First, there isn’t enough public finance for climate in India. The revenue deficit of the Central government is the lowest in 30 years as a percentage of total deficit. It is 40 per cent of total net borrowing, which means that for every one rupee we borrow, we spend 40 paisa on consumption. Only 60 per cent is spent on investments. So, the government of India is a consumer spending entity. And I don’t think it can provide public finance at scale. We should use public finance to leverage private finance. One example is green bonds, which provide a benchmark for private green investment.

Second, the private sector will invest in climate on commercial terms. And the business case for going green is quite strong because they are high-productivity investments and they realign resources into more efficient sectors.

But the problem is that the private sector’s appetite for long-term investments is low, and this is a cultural feature of the Indian private sector. It is not going to change just for climate finance. The Indian private sector prefers rent-seeking to long-term profits. What the government can do is front-load investments in areas where there are commercial benefits, like clean air and biodiversity. Clean air improves productivity. And biodiversity would mean less investment in disaster management and soil management because of land degradation. I come from Maharashtra. We never fished during the monsoon [breeding season]. This kind of sensitivity to biodiversity makes the production process more efficient. But it is not apparent to a trawler going to catch shrimp. So, the government may need to intervene.

Also Read | Why India’s forests are not storing enough carbon

Coal is a low-productivity sector in India. Do you see an opportunity to improve productivity by moving away from coal?

India is a low-productivity economy. Making climate improvements and other improvements on pollution and biodiversity involves converting this economy into a second-rate productivity economy, if not first-rate. Coal is a prime example of this. I am not against coal. I am against the way we mine, wash, transport, and use coal. All four of these stages involve high productivity losses, and they transfer social costs onto private individuals. If we are able to reduce these costs and coal is still competitive with other forms of energy, then I am all for it. But I don’t see how. And this is why I do not like coal. The workers who mine coal in Jharkhand, the way coal and fly ash are transported all over the country, and the way coal is utilised not just in power plants but also as cooking fuel create health costs for the nation. The costs of this resource far exceed the benefits. So, as an economic proposition, I am against coal.

There are arguments that, since mitigation action, such as using renewable energy, is increasingly cost-competitive, and fossil fuels also entail uncertainties in cases such as import dependency on oil and gas, climate action will become a simple rational decision. Do you agree? Do you think investing in renewable energy is a good strategy for industrial competitiveness in developing countries?

For renewable energy, as for any technology, I need to know whether we can do it or not. As far as I know, we can’t. We don’t have a renewable energy ecosystem in India that can compete on costs with China. Am I right?

If we’re talking about manufacturing capacity, then yes.

Yes. I am not talking about clean energy as a tamasha performance. Like we buy automobile parts from abroad, assemble them here and call it “Made in India”.

I have been hearing for 40 years that we will make jet engines. We still don’t. I am tired of “will make” future-tense propositions. I don’t see solar manufacturing [large-scale, fully self-manufactured panels and cost-competitive] in India happening before 2030. This is the outer limit of my time frame. So, let’s talk about today, not tomorrow. Then it becomes about importing fossil fuels versus importing solar panels. I think importing solar panels is better, and we can get some form of technological assistance from countries that, geopolitically speaking, do not want to see any particular country have a monopoly over the manufacture of solar panels and batteries. And we can make common cause with these countries. If we can do this, oil becomes less competitive, and it will sunset over time. But we also have vested interests in oil. We are one of the largest exporters of refined oil. We might have to consult the two A’s if we want to go out with an aggressive solar strategy. This is beyond my pay grade.

Also Read | The solution to climate anxiety is climate action: Jagadish Shukla

You once talked about the need for developing countries to bring the Brundtland Commission back into the conversation. This was in the context of inequitable patterns of consumption and environmental degradation. Could you elaborate?

We started this conversation about environmental sustainability when I was 15 years old. We were talking about how there is enough food in the world, but people still go hungry. There is enough water, but people still go thirsty. There is enough of everything, but people are still poor. So, the point is not about how much we are producing, which was the focus of the Industrial Revolution, but what we are consuming. The Brundtland report underpinned that patterns of consumption are unsustainable. Today, we focus on how outputs are produced. We ignore consumption. Hence, I say, much to the disappointment of my Western climate friends, that the singular focus on net-zero is a scam.

Climate change has thrown this conversation out the window. Now it does not matter how a unit of energy is used as long as it is produced using solar. Whether we light up Kochi airport or that same electricity is used to provide light for children [in rural India] to read is not a question that is asked. We advertise that Kochi airport is 100 per cent solar.

There was a proposal for a carbon tax on shipping recently. I am all for punitive tax, except I want it imposed on every ship that has burned coal or oil since the late 19th century. Lloyds of London [an insurance and reinsurance market] has this data. If we impose such a tax, Europe will be paying the rest of the world for the rest of my lifetime. If I say this to Europeans, I get a peculiar expression on their face. It is part anger, puzzlement and fear. This is what developing countries should aim for. Climate change is best used as a weapon of the weak. Global warming is not a summary result of all the unsustainability the world faces. It is one part. Addressing just that without addressing the root of the problem is unjust.

In India, we have bipartisan support for such ideas and I see it as a good thing. India has, so far, resisted narrow framings of climate. Prime Minister Narendra Modi can be faulted for many things but on one thing he is absolutely right about and has led from the front: Mission LiFE [Lifestyle for Environment]. Because LiFE has, at its core, the question of consumption and not just what we produce and how we produce. It’s not just a slogan as the Western public relations machinery makes it out to be. It is core to our position on climate and sustainability questions.

Rishika Pardikar is an environment reporter based in Bengaluru who covers science, law, and policy.