A year of protests hits a symbolic high with marches and peaceful demonstrations on the tragedy’s anniversary, but with the despised government more entrenched in power than ever.

Dijana Hrka walks down Boulevard Oslobodjenje (Liberation Boulevard) in Novi Sad, heading to the railway station. It is 1 November, one year since the railway station’s newly built canopy collapsed, killing her 27-year-old son, Stefan, and 15 others. In that year she has become one of the most recognizable faces in a movement demanding not only justice for the victims, but action against high-level corruption, as well.

Other marchers come up for a hug or condolences. She’s surrounded by her personal guard of military veterans. “I don’t feel safe. I was repeatedly threatened, portrayed as a public enemy by media that insulted me and my child’s memory. How would you react?” she says.

Radicalization

Student-led protests demanding the arrest of those deemed responsible, and the release of jailed protesters, began within days of the Novi Sad disaster just over a year ago. The first phase of the protest movement peaked on 15 March, with students at the forefront of perhaps the largest protest ever seen in Serbia: over 300,000 people gathered in Belgrade. Many hoped for a concession from President Aleksandar Vucic, or even his resignation, to make amends for what students saw as slow or stalled progress in investigating the canopy collapse.

But then, the entire complexion of the protest movement began to change. Why?

Vucic’s response to the March demonstration was harsher than ever. In April, he declared, “if the students want to remove me, they will have to kill me.” Then he radically shifted his narrative. No longer dismissing the students as idealists manipulated by the opposition, he and his allies now portrayed them as “foreign agents” fomenting a “color revolution” like Ukraine’s Maidan uprising in 2014.

The intensity and the frequency of the violence rose. Starting from March, the command of the police was replaced by figures affiliated with the ruling Serbian Progressive Party (SNS). Violence erupted in Belgrade on the night of the 28 June Vidovdan holiday: after a peaceful sit-in that drew about 150,000 people, some students clashed with the police.

That’s how radikalizacija (radicalization) started: to better withstand police violence, the movement got tougher. The army veterans, the only ones trained to confront a strong force, became essential. They earned gratitude, but also opened the door to some nationalistic and conservative stances. Banners of Orthodox groups who had lost trust in Vucic started to appear, as did symbols denouncing Kosovo. Still, this “noisy minority” never challenged the students’ demands, and it, too, started to push for early parliamentary elections.

On Vidovdan, many speeches exalted the national spirit of the Serbs that resisted the Ottoman Turks in the Middle Ages. Some praised the role of army veterans. The latter mostly provided “muscle”: unlike Vucic’s supporters, they never attacked journalists or tried to lead the movement. Vidovdan marked a turning point: the students remained at the heart of the protest, but burnout among many undergraduates opened a space for a wider spectrum of citizens.

During the summer of 2025, police aggression against students and journalists increased. Law student Aleksandra Nikolic, a participant in the March protest, was attacked by police in August in front of her faculty. “I’m not just a victim, I’m an activist: that episode doesn’t define me,” Nikolic told me.

The government’s steps to suppress the protest movement began to resemble hybrid war. Vesna Brajer, a professor of philosophy from Belgrade’s university, was a victim. “We were targeted by Informer,” the hardest-hitting pro-government tabloid. “Me, my husband, even my daughter, who is a student at the law faculty. No one was spared. My husband, as part of the NGO Rotary,was labeled a foreign agent.”

By September, however, the tension had started to fade. The students dropped the radikalizacija strategy and agreed to leave university buildings they had begun occupying on 15 November 2024, after SNS supporters attacked protesting students from Belgrade’s Drama Faculty. In 2025, at least 80 university departments were occupied. The end of the occupations helped professors recover part of the pay lost when the government tied their salaries to lessons taught. Some rallies occurred, but nothing comparable to March.

March to Novi Sad

“Mi nismo umorni” (we are not tired) reads a badge sold near Belgrade’s drama school. Around 8,000 people gathered outside the school on the morning of 30 October: students surrounded by ordinary folks cheering for them.

The march moves quickly from the school to the Novi Beograd district, and then the Zemun area. There we meet 19-year-old university freshman Lazar. “I came with my friends directly from Novi Sad to Belgrade. We’re now walking back home. I know it sounds weird, but it is what it is,” he says, smiling. Young students like him have taken a visible part in the protests since the disaster.

“In a few days, I’ll start lessons at the sports faculty in Novi Sad,” Lazar says. In early September, his university witnessed what some described as an unprecedented show of force. “They [the police] entered the faculty of literature to end the occupation, called by our rector. We had to hide in another building, in the dark, hunted by the police,” Natalija Petrovic, a reporter for the student media Blokada.info, told me back then. “They used such a massive amount of tear gas … it was insane.”

A mix of symbols appears as the marchers set out for Novi Sad on 30 October: crosses, pins saying “F*** SNS,” flags labeled “Kosovo is the heart of Serbia.” These are signs of a post-ideological movement, with ideologies juxtaposed rather than mixed. “We don’t know if this movement will be progressive,” Brajer says. “We don’t fight just for ourselves. The far right is advancing across Italy, Czechia, and the U.S. Our student’s fight encompasses a broader fight against authoritarianism, like 1968 in France.”

When the march heads out of Zemun, we say goodbye to Lazar, promising to keep in touch. The students peacefully enter Novi Sad on the night of the 31st as people from all across Serbia meet on Oslobodjenje Boulevard, in the town center.

The Anniversary

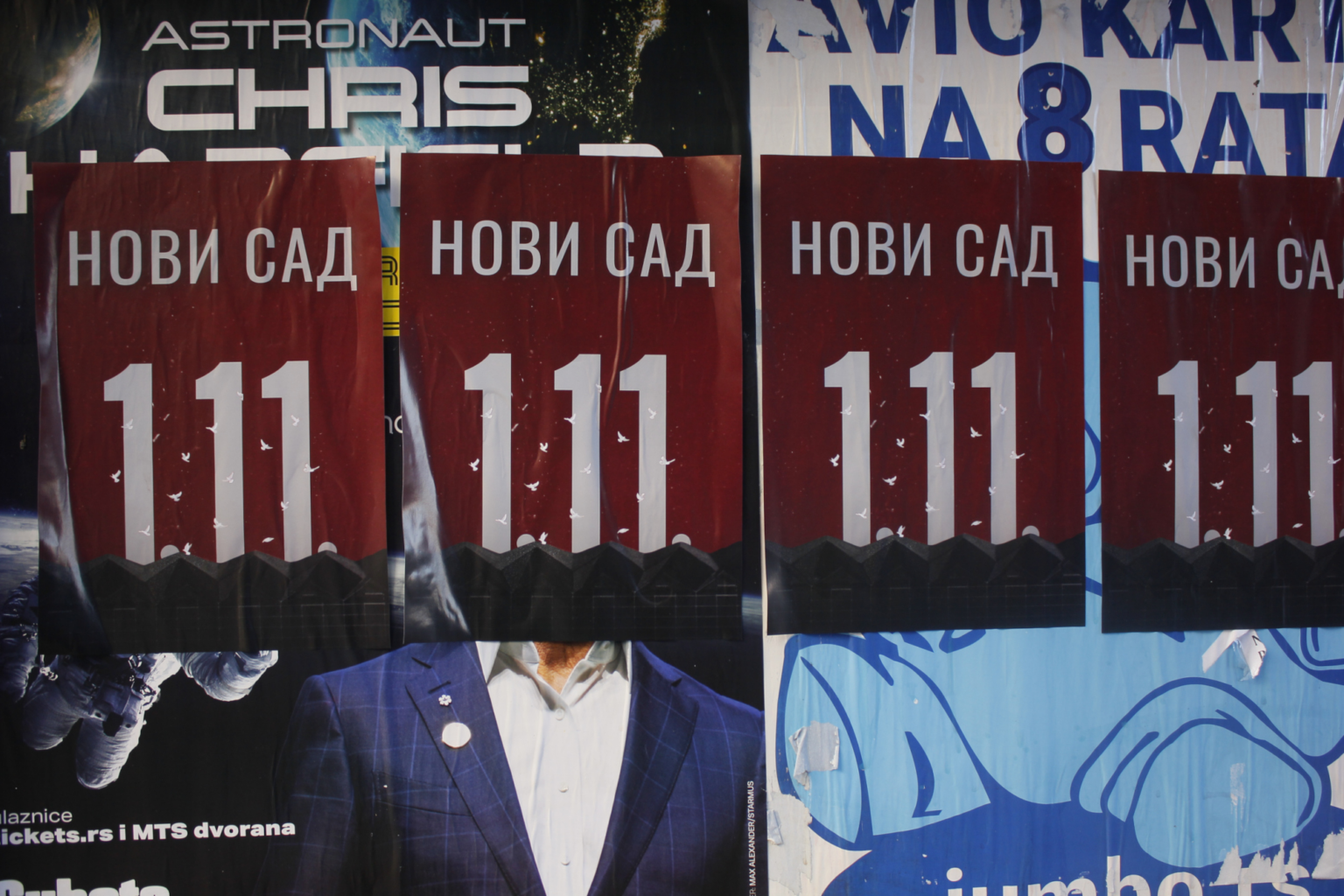

Demonstrators on the morning of 1 November fanned out to 16 gathering spots – one for each victim. High school students bring wreaths in their memory and an altar is set up below the statue of Svetozar Miletic, the journalist and lawyer who served as mayor of Novi Sad in the 1860s.

At 11:52 a.m., the exact time of the collapse, it’s the moment of the blokada, the traffic block: around 140,000 people stand in silence for 16 minutes, one for each victim. This crowd is not joyful or angry, but absorbed in sober reflection.

Many things have changed since 2024. The station in Novi Sad didn’t: the collapsed canopy remains unreplaced. “Citizens are bitter – the authorities are avoiding determining what exactly happened and why. But this can happen again in schools, post offices, kindergartens,” Ivan Miladinovic and Mirna Radin Sabados, co-leaders of the Zeleno-Levi Front (Green-Left Front, a Green political party) in Novi Sad, wrote in a joint email. Trains cannot use the station until repair work is completed. “Without a station, life and work haven’t been the same. We don’t even know what will happen to the building,” they added.

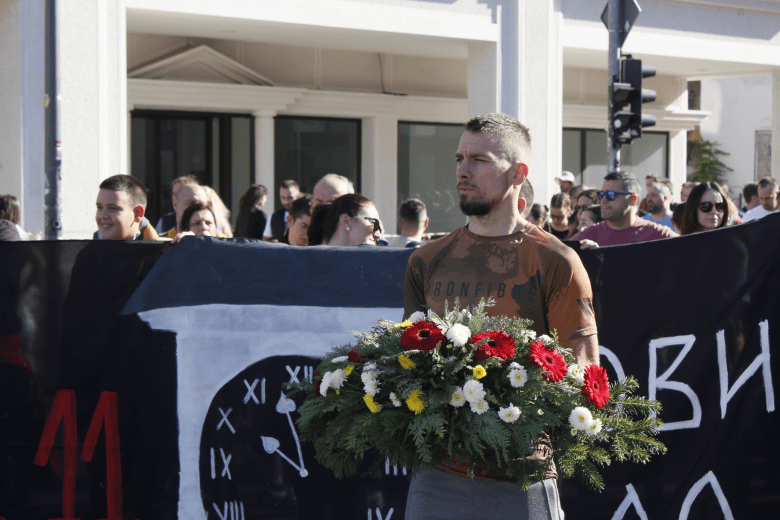

In Novi Sad, all eyes are on Dijana Hrka. Many people ask for a selfie, her guard of veterans escort her and chooses who can and cannot get too close, for her own safety.

Once on the stage, her grief turns into strength. “Thanks to the students and all the citizens who kept me alive. Today is the saddest day for all of us: Novi Sad is crying,” she says. “But I’m fighting to avoid any mother, sister, or anyone among us having to cry [again]. I have a message for Aleksandar Vucic: call new elections. I’ll fight for that alone, by going on hunger strike in front of the parliament. I need to know who killed my child – someone must be responsible.”

Surrounded by her security detail, Dijana Hrka (in white) greets a journalist during the commemorative march for the victims of the Novi Sad disaster.

Surrounded by her security detail, Dijana Hrka (in white) greets a journalist during the commemorative march for the victims of the Novi Sad disaster.

Hrka’s speech is the most intense moment of the day. The afternoon demonstration passes without further speeches or any police violence, creating a rare moment of sincere, shared grief. Even Vucic says that “this should be a moment that unites us, not one of division” and that he regretted some of his angry comments about the students.

Welcome Back, Violence

The main obstacle to Hrka’s brave project is “Cacilend,” a pro-government camp in Belgrade, set up last March by “students who want to study,” demanding an end to the student occupations of university buildings. The universities are teaching again, but the camp is still there. There have been numerous clashes in these months, with countless incidents of violence and intimidation. Most of the “campers” are middle-aged.

On the night of the 2nd, when Hrka starts her hunger strike, the Caci push her back. So, she camps on one side of Nikola Pasic Square, just in front of the fence around Cacilend. Around 2,000 students and other supporters join her.

Many ambiguous people are in the crowd. One, calling himself Branko, notices my press vest. Speaking perfect Italian, he asks who I report for and my opinion about Vucic. A government agent, I assume. A Serbian journalist who wished to remain unnamed says, “The Caci are just normal citizens, we cannot recognize them by their physical appearance. We cannot know who we can trust and who we can’t. This is Vucic’s main victory.”

Large numbers of police and Caci flood the square. The tension is palpable. Each side shouts insults at the other; many fireworks fly from Cacilend, a few are thrown back. That night, 37 people are arrested and Vucic opines that the students are getting nervous because the protests are failing. Dijana Hrka’s tent is unscathed. But the strain is reminiscent of last summer.

Looking Ahead

The following days, the clashes continue. The academic year officially began, but the peace of the first of November is gone. The main question is: what now?

The protest movement surely wants to get rid of Vucic by political means. But as Mirka, a mother and active protester, tells me, “We cannot just remove him, we need to dismantle his system. We didn’t do it in 2000 with Slobodan Milosevic, and this brought us Vucic.”

Elections may be called anytime between autumn 2026 and spring 2027. Will a student party run? Students announced the launch of their own electoral list from a stage during the Vidovdan celebrations/protests in Belgrade. Support remains uncertain: polls vary from 9% to as high as 45%. The candidates – who will not be students – and their program, worked out in undergraduate assemblies, will be revealed once the elections are announced. Vucic has already designated Vladan Djokic, the rector of Belgrade University, as the main opponent of his SNS.

But what to do with the current opposition? Vesna Brajer is trenchant: “They had 13 years to defeat Vucic, but they preferred to have agreements with him. Nobody trusts them anymore, only the students can beat SNS.” Law student Luka Markovic shared Brajer’s opinion in an interview with the daily Danas: the opposition must step aside to let the students win. He didn’t even contemplate the possibility of losing.

Three young demonstrators in the square fronting the parliament building on the night of 2 November.

Three young demonstrators in the square fronting the parliament building on the night of 2 November.

Miladinovic and Sabados don’t agree. Their own party emerged from a protest movement and so they support the students, they said. “But we believe that coordination between students, citizens, activists, and the opposition is vital. We should agree on the next steps to get fair elections and to immediately stop the violence against citizens.”

Nobody can foresee how things will look on the second anniversary of the Novi Sad disaster. The situation is still in flux. Dijana Hrka ended her hunger strike on 17 November. Whether the protest movement can transition from symbolic shows of dissent to real political action is anybody’s guess.

Camillo Cantarano is a journalist from Rome. He has written for several prominent Italian news outlets on the Balkan region, migration policies, the Palestinian-Israel war, and organized crime and civil rights in Italy.

Photos by Camillo Cantarano.