Italian Dardo IFVs are approaching the end of their service life. This naturally brings up the issue of a possible transfer to Ukraine—specifically, how feasible such a move would be, when it might occur, and whether it would make practical sense at all.

The discussion intensified after the first Lynx IFV arrived in Italy. The Lynx is intended to replace older armored platforms. So far, only 21 vehicles have been ordered, although long-term plans call for the acquisition of up to 1,050 units.

Lynx IFV replacing the Dardo in Italy and also offered to Ukraine / Photo credit: Rheinmetall

Lynx IFV replacing the Dardo in Italy and also offered to Ukraine / Photo credit: Rheinmetall

While Italian politicians often appear in public discourse to be hesitant or even skeptical about providing military aid to Ukraine, the reality is more nuanced. Italy has already transferred a significant number of 155 mm M109L self-propelled howitzers, VCC-1/2 armored personnel carriers, Puma armored vehicles, and C1 Centauro wheeled tank destroyers.

These deliveries are usually carried out discreetly. Information typically emerges through analysts, insiders, or visual evidence during transportation, or only after the equipment has entered service with the Ukrainian military. Occasionally, such transfers are acknowledged more openly as part of specific aid packages, as has been the case with the SAMP/T air defense system.

Italian VCC-2 armored personnel carrier in service with a rifle battalion of the Donetsk regional police

Italian VCC-2 armored personnel carrier in service with a rifle battalion of the Donetsk regional police

This establishes a precedent for the quiet transfer of military equipment to Ukraine, whether from storage bases, as with APCs, or from platforms scheduled for retirement, such as the Centauro. In theory, a similar decision could be made regarding tracked IFVs.

At present, Italy operates only 200 Dardo IFVs across three regiments.

These vehicles are armed with a 25 mm autocannon and two TOW anti-tank

guided missiles. Their protection level includes resistance to 25 mm

rounds in the frontal arc and 14.5 mm rounds on the sides. Despite their

respectable capabilities, the limited fleet size significantly

constrains the potential scale of any transfer and could create

challenges in terms of maintenance and the replacement of combat losses.

Italian Dardo infantry fighting vehicles / Open-source illustrative photo

Italian Dardo infantry fighting vehicles / Open-source illustrative photo

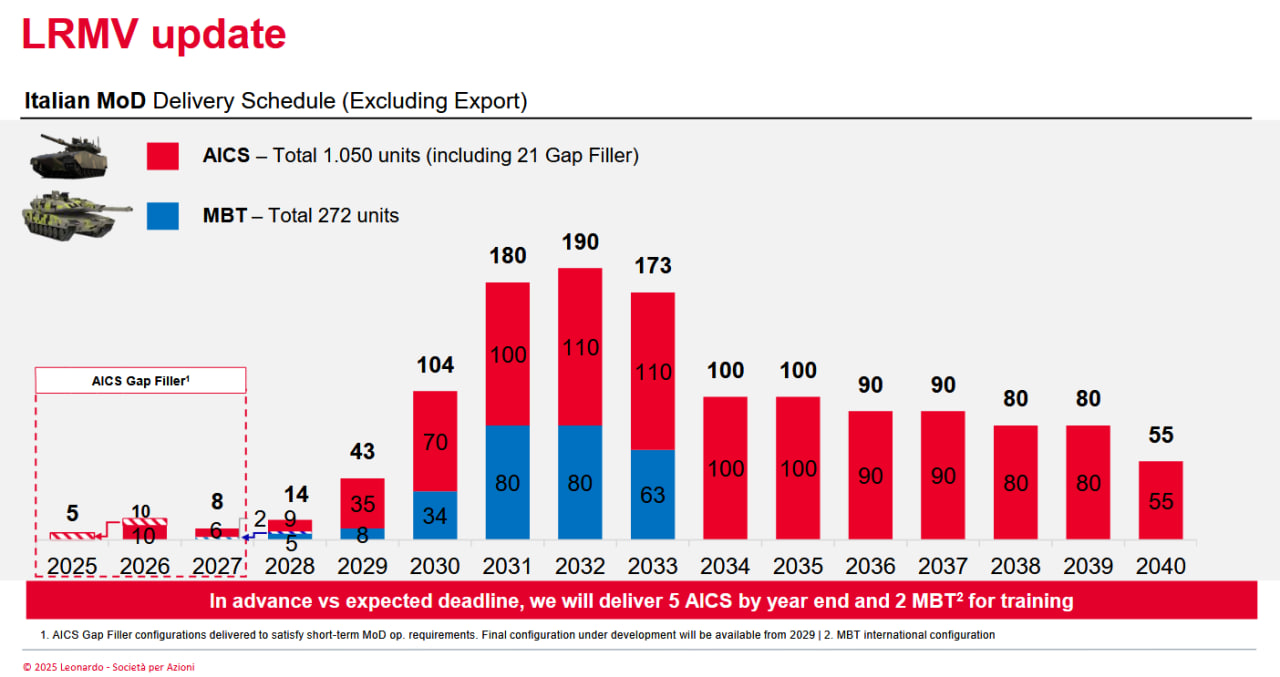

Moreover, this is not the only issue. Deliveries of the KF41 Lynx to the Italian Army are expected to proceed at a relatively slow pace. This year, only five vehicles will be delivered in the baseline “Hungarian” configuration, with the next 16 units scheduled for 2026–2027 and equipped with a domestically developed turret.

Based on currently known timelines, Italy is expected to receive approximately 160–180 Lynx IFVs by 2030, assuming no further delays. This means Ukraine would likely have to wait a considerable amount of time before any realistic decision on transferring Dardo vehicles could be made.

Timeline of armored vehicle deliveries to Italy by LRMV / Chart from a Leonardo presentation

Timeline of armored vehicle deliveries to Italy by LRMV / Chart from a Leonardo presentation

In theory, Italy could approve the reinforcement of Ukrainian forces before the replacement process is fully completed. However, this scenario appears unlikely. When combined with the limited number of available vehicles, the transfer of Dardo IFVs as military aid seems to be a largely unrealistic option and one that would take a long time to materialize.

At the same time, Ukraine is experiencing a significant shortage of armored vehicles. In this context, the delivery of almost any armored platform could strengthen the Defense Forces. The key question is whether it would be more effective to focus on more widely available IFVs, such as the CV90 already in service, or the KF41 Lynx, which could potentially be localized if sufficient funding were secured.