The announcement by Minsk that russian forces had deployed the Oreshnik intermediate-range ballistic missile in Belarus triggered the appearance of yet another “scare story” in some Ukrainian media — probably exactly the reaction the Kremlin was hoping for. Allegedly, this latest “wunderwaffe” could now reach European capitals, including Kyiv, in just a few seconds.

Specifically, it was asserted that the Oreshnik would take just 1 minute 51 seconds to reach Kyiv, 1 minute 44 seconds to Lutsk, 2 minutes 24 seconds to Lviv, 1 minute 4 seconds to Vilnius, and 2 minutes 23 seconds to Warsaw.

From the Defense Express perspective, this is complete nonsense. These figures were derived by simply dividing the distance to each city by the Oreshnik’s claimed top speed of 12,300 km/h — without any understanding of how a ballistic missile actually flies.

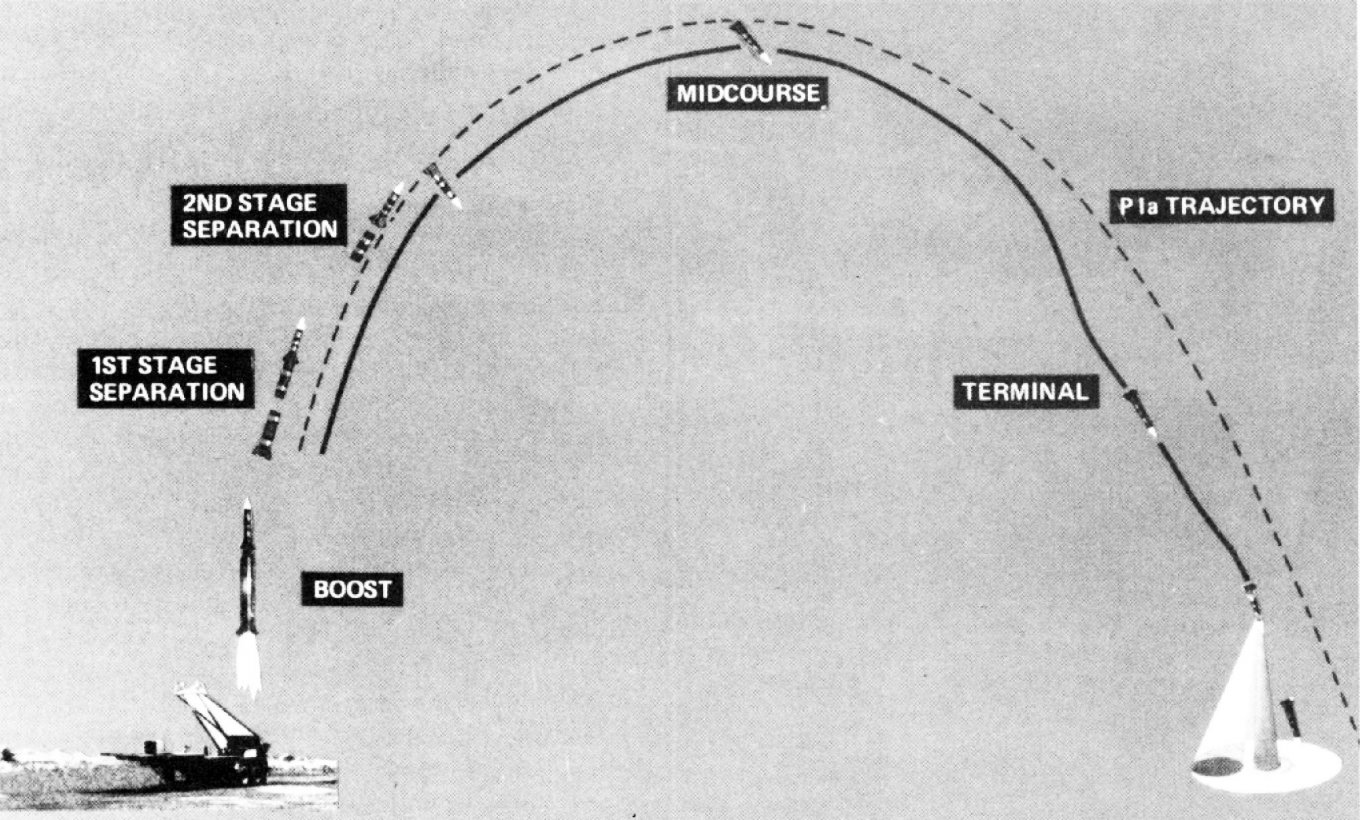

The Oreshnik is a ballistic missile, meaning it follows a steep ballistic trajectory rather than traveling in a straight line. Moreover, its maximum speed is achieved only briefly, after a prolonged acceleration phase. After that, the missile largely travels by inertia. As such, dividing the distance between the launch and impact points by maximum speed is fundamentally incorrect.

Trajectory and key flight phases of the Pershing II intermediate-range ballistic missile

Trajectory and key flight phases of the Pershing II intermediate-range ballistic missile

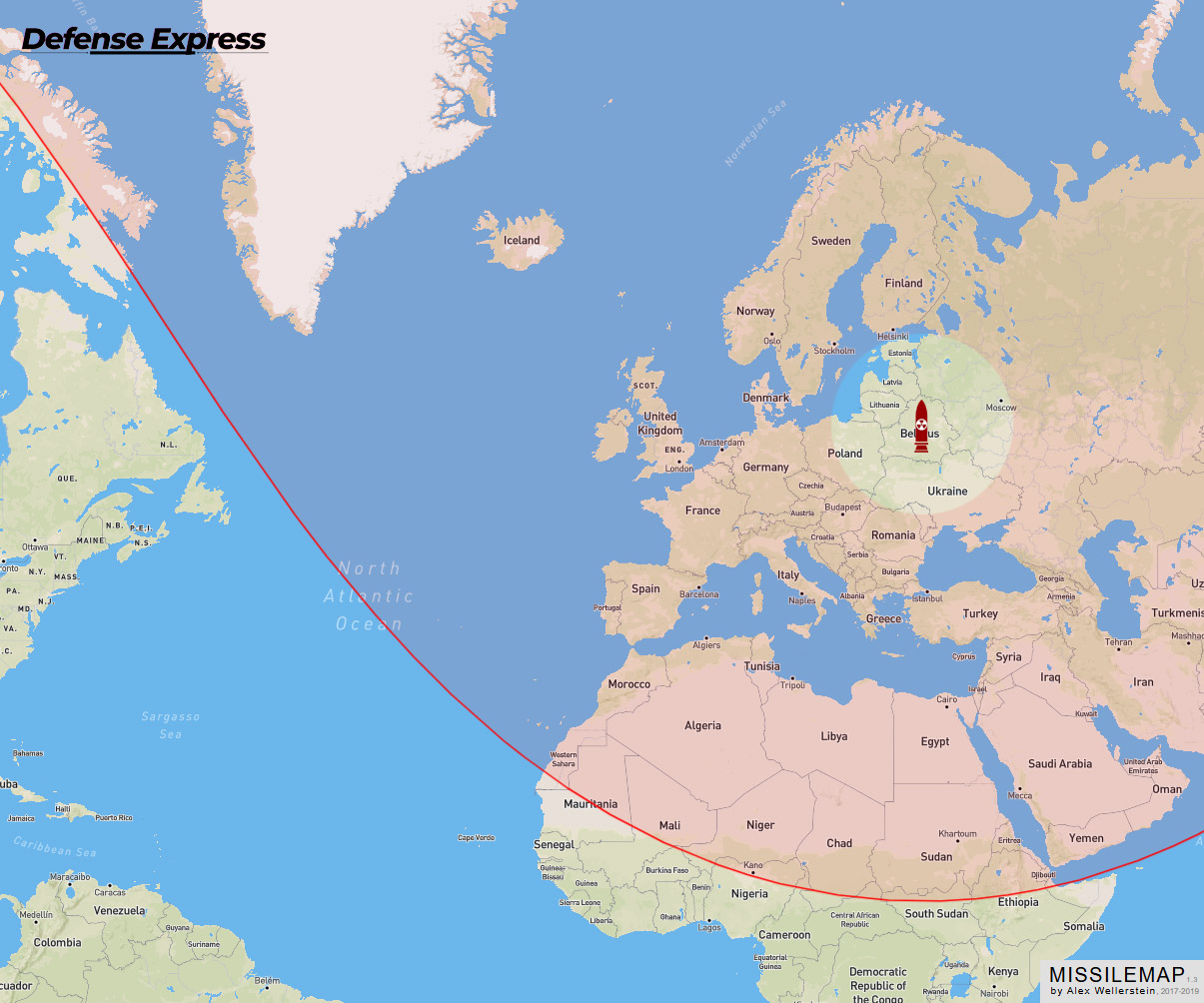

More importantly, paradoxical as it may sound, all of the cities listed above, including Kyiv and most of Ukraine, are in fact outside the Oreshnik’s engagement envelope. Like all two-stage solid-fuel intermediate-range ballistic missiles, the Oreshnik has not only a maximum but also a minimum flight range.

These parameters are known, as they were publicly disclosed by representatives of Ukraine’s security services during a briefing attended by the President of Ukraine on 31 October 2025. According to that briefing, the Oreshnik has a minimum range of 700 km and a maximum range of 5,500 km. Accordingly, its approximate engagement envelope can be illustrated as follows.

As a result, the Oreshnik cannot strike Kyiv from Belarus at all, because the distance from the farthest point of Belarus to Ukraine’s capital is only 660 km. This, of course, does not negate the fact that this mobile ground-based missile system would pose a serious threat to Europe and other regions in the event of a nuclear war.

Why this is the case requires further explanation.

Historically, ballistic missile range control relied heavily on shaping the trajectory. For long-range strikes, the trajectory was made flatter; for shorter distances, it was made very steep. This allowed the missile’s engines to burn for roughly the same duration, while the actual distance covered changed. However, the Oreshnik is a more modern, two-stage solid-fuel missile.

To understand how it works, it is useful to examine its closest Soviet analogue, the RSD-10 Pioneer intermediate-range ballistic missile, on whose principles the Oreshnik was developed. The two systems have very similar range parameters: the Pioneer had a minimum range of about 600 km and a maximum of roughly 5,000 km.

RSD-10 Pioneer intermediate-range ballistic missile

RSD-10 Pioneer intermediate-range ballistic missile

The RSD-10 Pioneer’s flight profile worked as follows. The first stage had to burn to completion (with only an emergency shutdown option) so that the second stage could ignite at the required altitude. This is critical, because the impulse of the second stage is calculated for a very specific operating environment, which differs dramatically between the lower atmosphere, upper atmosphere, and near-vacuum conditions.

Unlike liquid-fueled engines, which can be throttled and even restarted multiple times, solid-fuel rocket motors offer no such flexibility.

RSD-10 Pioneer reentry vehicle (warhead)

RSD-10 Pioneer reentry vehicle (warhead)

The second stage of the RSD-10 Pioneer was equipped with a thrust termination mechanism, known as a cutoff. This allowed coarse control of flight range not only through trajectory shaping. Once cutoff occurred, precise guidance of the reentry vehicle and warhead separation followed. This was carried out using orientation and maneuvering thrusters, which themselves are designed to operate under specific environmental conditions.

The sequential operation of the stages, their separation, maneuvering, and warhead deployment all take time, and that time translates directly into distance traveled. This is what ultimately defines both the minimum and maximum range of the missile.

One more important detail should be noted. At the same official briefing mentioned above, it was stated that russia currently has only one operational Oreshnik missile. Another was expended during testing, while a third was successfully destroyed during a Ukrainian special services operation in the summer of 2023.

And while Minsk attempts to intimidate audiences with a missile it neither owns nor possesses in meaningful numbers, Defense Express urges readers to support the Yedynozbir fundraiser for interceptor drones.