The Eifel region, part of the Rhenish Massif in western Germany, consists of hundreds of volcanic cones and explosion craters, known as maars, scattered across the countryside. These include the striking Laacher See Lake that fills the remnants of a giant volcanic caldera.

About 12 900 years ago, during the Late Pleistocene, the Laacher See volcano erupted catastrophically in one of the largest volcanic events in Central Europe in the last 100 000 years.

The eruption reached Volcanic Explosivity Index 6, producing approximately 6 km³ of tephra (~2 km³ dense rock equivalent magma) and dispersing pumice and ash across much of Europe.

The eruption led to the collapse of the magma chamber roof, forming a caldera that later filled with water, creating the circular Laacher See lake observed today.

Geologically, the Eifel belongs to the European Cenozoic Rift System; a diffuse zone of crustal stretching that also runs through the Rhine Graben and Massif Central in France. Although far from any plate boundary, this rift system remains slowly deforming. Persistent CO2 emissions, minor earthquakes, and crustal uplift at about 0.75 mm (0.02 inches) per year indicate that the region is not extinct but dormant.

The largest seismic experiment in Germany

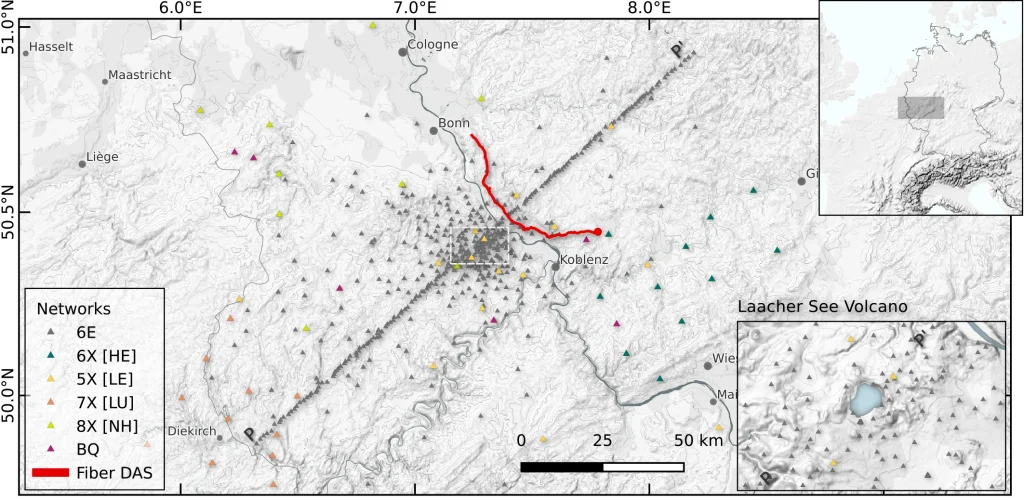

Location of the approximately 500 seismic stations that were installed in the Eifel region between September 2022 and August 2023 as part of the “Large-N Experiment” in order to obtain the highest possible resolution image of the magmatic subsurface. In red: the fibre optic cable that was used for supplementary measurements. Credit: Dahm et al. (2025)

Location of the approximately 500 seismic stations that were installed in the Eifel region between September 2022 and August 2023 as part of the “Large-N Experiment” in order to obtain the highest possible resolution image of the magmatic subsurface. In red: the fibre optic cable that was used for supplementary measurements. Credit: Dahm et al. (2025)

To understand what lies beneath, scientists from the GFZ German Research Centre for Geosciences and the University of Potsdam conducted the Eifel Large-N experiment between September 2022 and August 2023. It was the largest passive seismological deployment ever undertaken in Central Europe.

More than 494 seismic stations were distributed across the Eifel volcanic fields, spaced as closely as 1 km (0.6 miles) in the eastern sector. The array was complemented by a 64 km (40 miles) fiber-optic cable used as a distributed acoustic sensor, capable of detecting tiny ground vibrations along its entire length.

The dense coverage allowed researchers to record thousands of small earthquakes and image the upper crust in unprecedented detail, essentially performing a medical CT scan of the volcanic system.

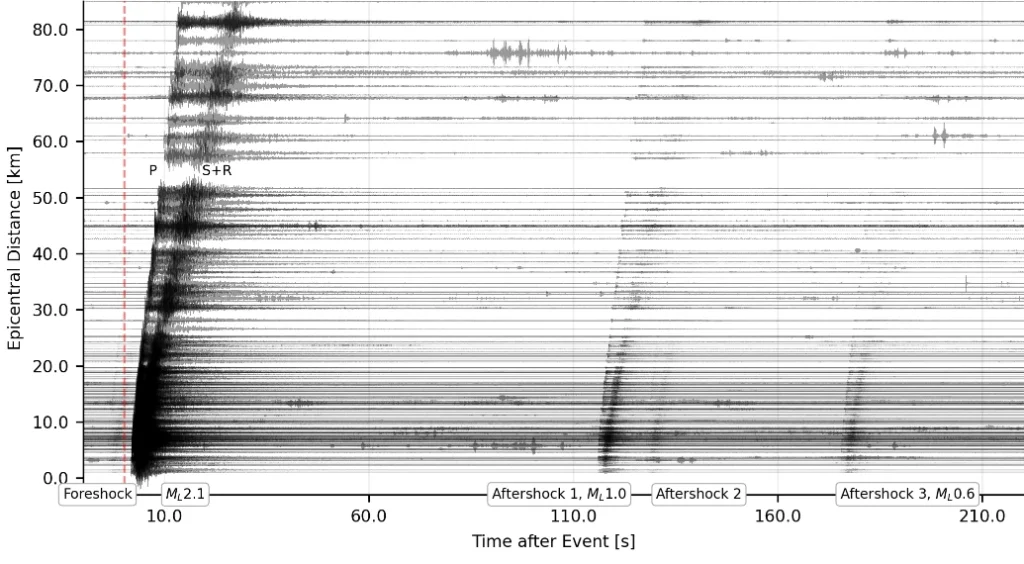

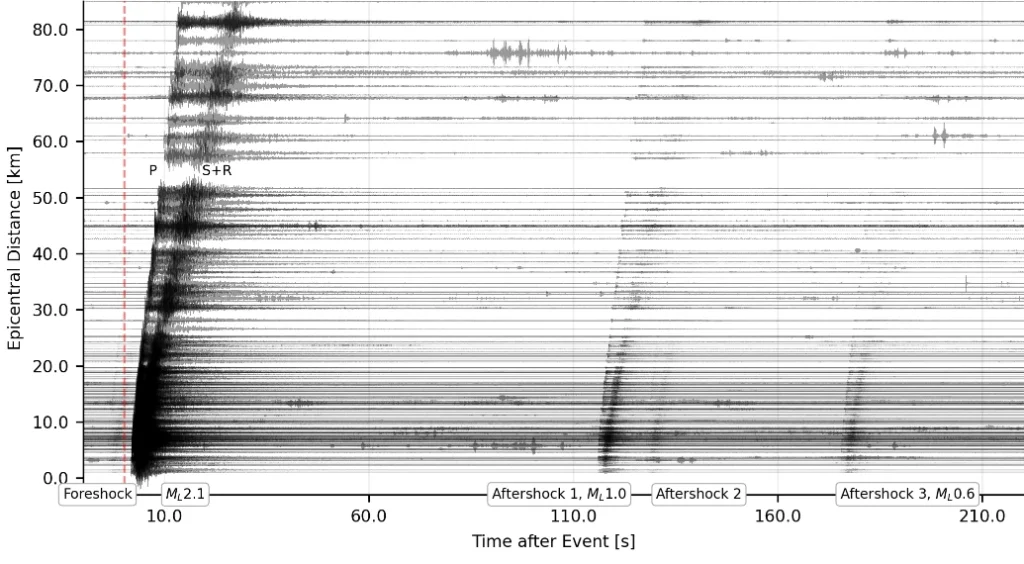

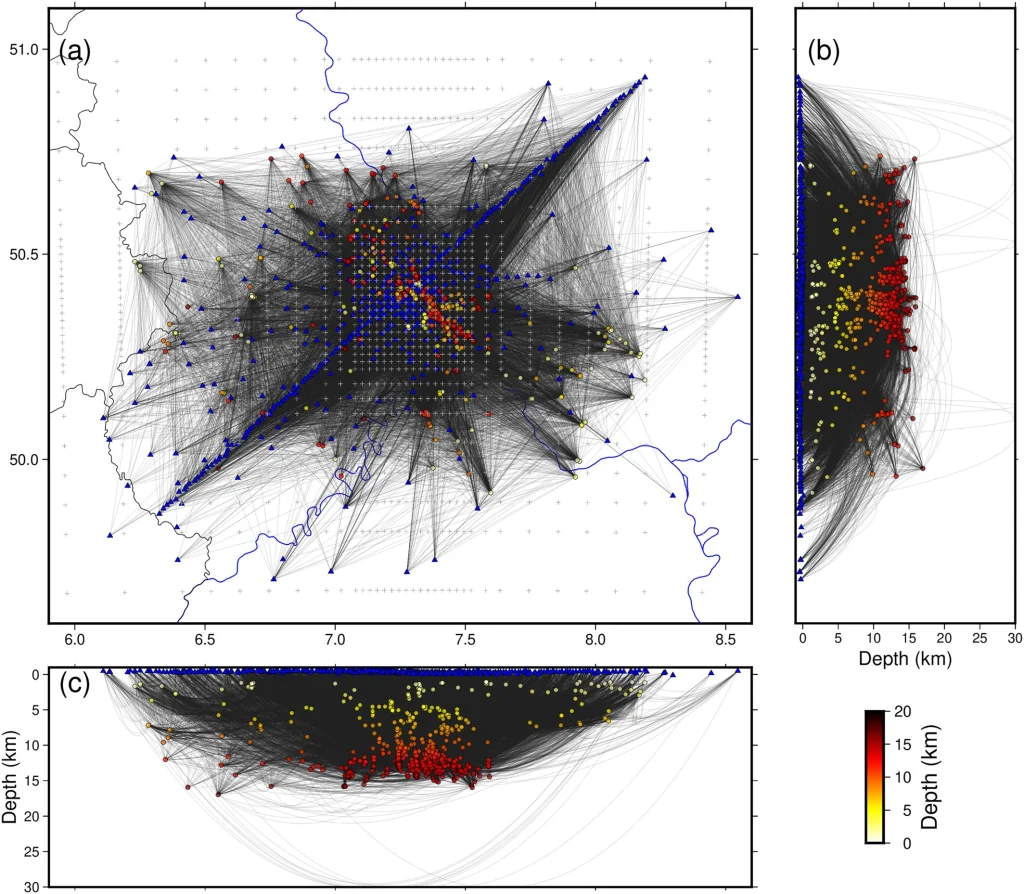

Data analysis employed machine-learning algorithms for automatic event detection and precise localization, combining more than 60 000 P-wave and 50 000 S-wave phase picks.

The magma reservoir under Laacher See

Record section on a part of the large-N stations (Z component) for a sequence of earthquakes beneath Kruft about 10 km (6.2 miles) from LSV at depth of about 10 km. Magnitudes range from ML 2.1 to below ML 0.4. Traces are unfiltered and scaled to their maxima. Credit: Dahm et al. (2025)

Record section on a part of the large-N stations (Z component) for a sequence of earthquakes beneath Kruft about 10 km (6.2 miles) from LSV at depth of about 10 km. Magnitudes range from ML 2.1 to below ML 0.4. Traces are unfiltered and scaled to their maxima. Credit: Dahm et al. (2025)

The high-resolution tomographic model revealed a cylindrical low-velocity, high VP/VS ratio anomaly directly beneath the Laacher See volcano. The feature extends from about 2–10 km (1.2–6.2 miles) depth, with an estimated volume of roughly 75 km3 (18 miles3).

The anomaly dips about 53° southeast, intersecting the Siegen Thrust at around 10 km depth, a geometry that had slipped under the radar of previous lower-resolution studies.

According to the researchers, this structure likely represents a partially molten or fluid-saturated reservoir, the remnant of the magma chamber that fueled the 13 000-year-old eruption. Microearthquakes cluster around the margins of the anomaly, suggesting zones of elevated pore pressure or thermal stress.

At greater depths, between 10 and 45 km (6–28 miles), a series of deep low-frequency volcanic earthquakes traces a vertical channel connecting the upper mantle to the crust — a pathway for rising CO₂ and magmatic fluids.

Thousands of microearthquakes mark active zones

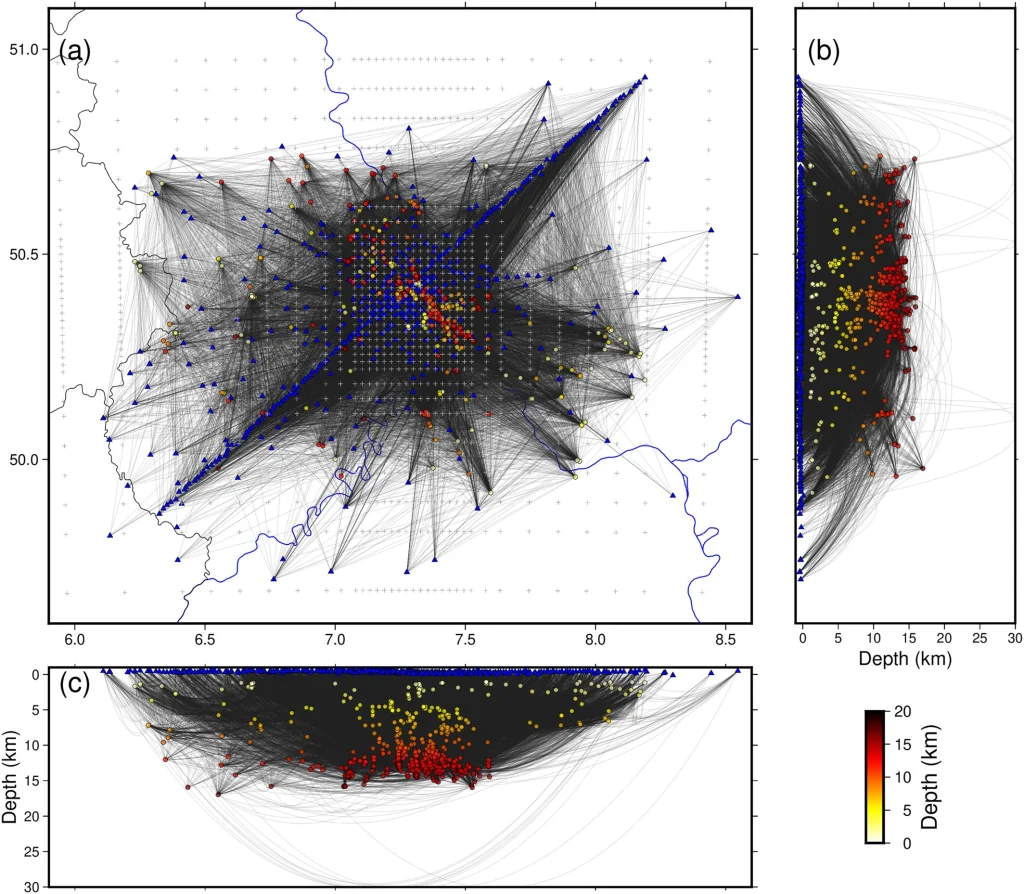

Ray-path coverage for tomographic inversion. (a) Map view. (b) N-S projection. (c) E-W projection. Gray crosses in panel (a) show the grid nodes for single inversion. Local earthquakes are marked as dots, with colors corresponding to their depths (see color bar). Blue triangles are the stations. Credit: Zhang et al., 2025

Ray-path coverage for tomographic inversion. (a) Map view. (b) N-S projection. (c) E-W projection. Gray crosses in panel (a) show the grid nodes for single inversion. Local earthquakes are marked as dots, with colors corresponding to their depths (see color bar). Blue triangles are the stations. Credit: Zhang et al., 2025

During the 12-month experiment, more than 1 000 local microearthquakes were recorded in the East Eifel Volcanic Field. Most were located along the Ochtendung Fault Zone, a near-vertical structure at the eastern margin of the Neuwied Basin.

Moment-tensor inversion of 192 well-recorded events (magnitudes Mw 0.6–2.7) revealed predominantly strike-slip faulting, with some normal-fault components. The orientation of the P-axes varied systematically, indicating subtle stress rotations influenced by pressure changes in the underlying reservoir.

Such behavior is typical of fluid-driven seismicity, where magmatic gases or hydrothermal fluids migrate along existing fractures, temporarily altering local stress fields. These small quakes, while imperceptible at the surface, map the invisible heartbeat of the crust.

Fluids and faulting in the crust

Seismic reflections and tomographic contrasts beneath the Neuwied Basin also point to fluid accumulations at various crustal levels. These zones of reduced velocity and high attenuation likely contain CO2-rich fluids or hydrothermal brines trapped in porous layers or fractures.

Their presence matters: fluids can lubricate faults, lower their strength, and trigger microseismicity even without significant tectonic stress. In the Eifel, these processes appear to connect the deeper magmatic system with the upper crust, sustaining ongoing CO2 degassing observed at the surface.

This coupling between fluids and faults helps explain why the region experiences sporadic bursts of seismic activity despite its otherwise quiet appearance.

No signs of imminent eruption

The new findings do not indicate any short-term eruption risk. The system remains dormant, and the observed seismic and fluid activity reflects deep crustal dynamics rather than impending volcanic unrest.

However, the results confirm that the Eifel volcanic field is not extinct. Its subsurface remains thermally and mechanically active with a complex network of magma, gas, and faults still evolving within the continental crust.

Continuous monitoring of microseismicity, deformation, and gas emissions will be essential to detect long-term changes in this delicate balance.

References:

1 Microseismicity Reveals Fault Activation and Fluid Processes Beneath the Neuwied Basin and Laacher See Volcano, East Eifel, Germany – Laumann P. et al. – Geophysical Journal International – November 22, 2025 – DOI: 10.1093/gji/ggaf475

2 A Seismological Large-N Multisensor Experiment to Study the Magma Transfer of Intracontinental Volcanic Fields: The Example of the Eifel, Germany – Dahm T. et al.– Seismica – October 10, 2025 – DOI: 10.26443/seismica.v4i2.1492

3 The Upper Crustal Structure of the Eifel Volcanic Region (Southwest Germany) From Local Earthquake Tomography Using Large-N Seismic Network Data – Zhang H. et al. – AGU – November 5, 2025 –DOI: 10.1029/2025JB031338