LANSING, Mich. — Amidst this year’s global proliferation of artificial intelligence, there has been a simultaneous swelling in demand for data centers — the massive facilities that power the electricity-hungry technology that is AI.

While data centers themselves are not new, those close to the industry have said the scale and speed of growth now underway is entirely different.

Billions of dollars are being poured into the industry by major tech companies to build more data centers as they race toward AI’s promised potential.

Development proposals have been picking up pace throughout states in the Midwest, including Michigan.

Lawmakers have compared the global push for AI dominance to the space race, with utmost importance placed in “beating” China to the “finish line.”

Former Google CEO Eric Schmidt has said it is “crucial that America get there first.”

“Why is this all important? When you build these systems, you have intelligence in the computer and then eventually human-level intelligence,” Schmidt said in front of lawmakers earlier this year. “Some people think it’s within three to four years. Then, after that, you have something called “super intelligence,” and super intelligence is the intelligence that’s higher than of humans. We believe as an industry that this could occur within a decade.”

Schmidt added that many of these data centers are targeting the country’s heartland because they “have a huge economic impact, positively, on areas that typically do not have the kind of growth that they would like.”

While proponents argue data centers are necessary to support modern technology and can bring investment into local communities, critics argue that data centers pose risks to personal health and the environment.

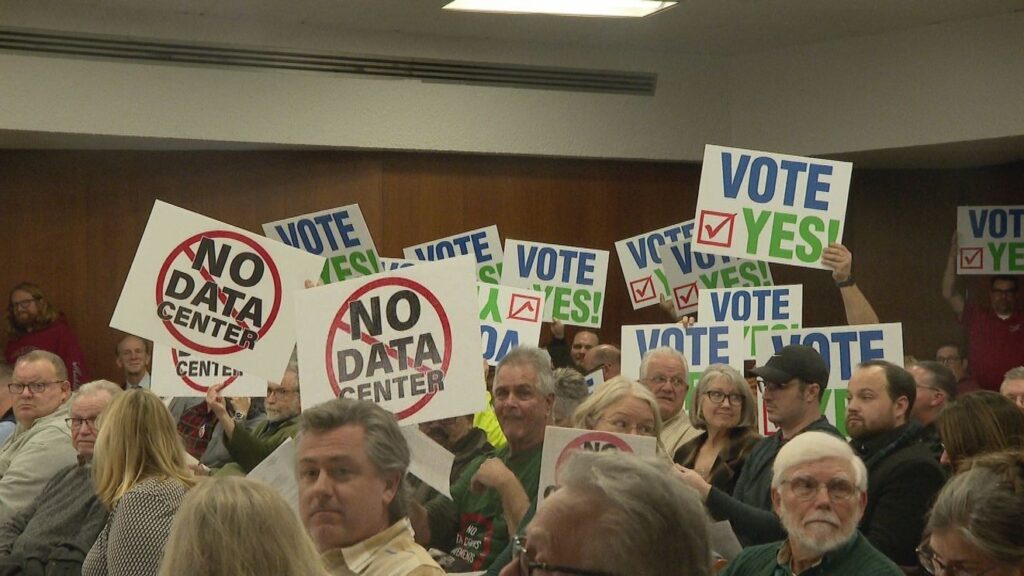

Of the many communities throughout Michigan facing zoning inquiries for data centers in 2025, there has been a seemingly united front from residents asserting that they do not want that kind of development where they live.

News Channel 3 attended a number of full-house meetings related to data centers this year, including recently in Marshall and Lowell townships, as well as an organized protest held at the State Capitol.

Among opponent concerns for the environment, such as water supplies, pollutants, and electric grid capacity, the majority stem from the fact that data centers are filled with servers that require enormous amounts of electricity and cooling technologies to operate.

The Environmental Law and Policy Center (ELPC) has been hearing those concerns from Michiganders and throughout the Midwest, according to Katie Duckworth, a senior associate attorney.

“People are asking fundamental questions about who ultimately benefits from the development of data centers,” Duckworth said, “and demanding real transparency on those issues.”

Duckworth said the ELPC is actively advocating for balance between technological advancement and the protection of Michigan’s resources.

It is crucial to get ahead of the influx, according to Duckworth, with proper incentives, planning, and requirements, such as mandating companies to pay their share for electric costs and adopting the best available technologies for the environment.

For example, there are two primary approaches to keeping data centers from overheating: open-loop and closed-loop systems.

Chris Schrock, a senior energy engineer with Development Solutions Midwest, explained that there are benefits and trade-offs to both systems.

Open-loop cooling pulls water directly from municipal systems, such as rivers or lakes, which circulates it through the facility to absorb heat and then discharges the remaining water.

While more energy-efficient, Schrock said, this method consumes large volumes of water with additional losses due to evaporation.

Closed-loop systems, by contrast, recirculate the same water repeatedly through pipes, heat exchangers, chillers and cooling towers.

Since the water is reused, they significantly reduce overall water consumption, according to Schrock. The trade-off, however, is energy.

Most data centers currently being planned in Michigan are using closed-loop systems, Schrock told News Channel 3.

“Closed-loop systems conserve water, but they require a lot more electricity to run pumps, fans and chillers,” Schrock said. “So, you’re saving water, but increasing demand on the electric grid.”

Data centers are among the largest electricity users on the grid, creating challenges and concerns, but also offering potential investment into communities and into grid infrastructure, according to some.

Brandon Hoffmeister, Consumers Energy’s senior vice president for strategy, sustainability and external affairs, has told News Channel 3 that data centers will not lead to any increase in electric rates for customers, but could be used to pay for much-needed infrastructure upgrades, building a stronger and more reliable electric grid for the State of Michigan.

Schrock explained, “A data center is a centralized, very large electric customer paying very large electric bills. The investment that goes into serving a customer like that often results in a more reliable electric network for that immediate neighborhood.”

Utilities engineers, he added, plan years in advance for large new customers, upgrading infrastructure to meet future demand. Schrock also added that data center development needs to be carefully planned and managed by communities and regulators.

“I’m not for or against any one data center,” he said. “I understand that data centers are necessary for the way our society uses technology, but it’s appropriate for each community to ensure they’re planned well and that they aren’t a detriment to the environment or the local electric grid.”

That sentiment has been echoed at public meetings across West Michigan, where residents have voiced strong opinions toward choice, transparency, and community protections.

Looking ahead to 2026, more data center proposals are expected to land before the Michigan Public Service Commission.

Some technology leaders have indicated, however, that the future of data centers could look very different, including experimental ideas like placing facilities in space.

The Lansing Board of Water and Light has recently announced an innovative approach: a proposed data center project that would capture waste heat generated by servers and use it to heat water for the city’s district heating system.

The idea is to reduce the amount of natural gas typically burned to produce that heat, repurposing a byproduct of data processing into a community benefit.

“It’s a really innovative way to improve efficiency,” Schrock described, “by using the heat that data centers already produce to offset other energy use.”

As the world, country, Midwest, and State of Michigan navigate the rapid rise of AI-driven infrastructure, many people have made it clear that they intend to be involved every step of the way.

At one recent data center proposal hearing in Marshall, a resident told his local officials about his fellow neighbors, “We’re going to do whatever it takes.”