Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania are building up a continuous front against the possibility of aggression and securing their borders with Russia and Belarus. The Baltic Defence Line foresees physical barriers and defence systems all along the potential front line. But will it be enough?

A rural landscape of small remote farms, wide rolling fields, lush meadows and solitary forests. The countryside is beautiful and tranquil at the end of summer in this sparsely populated and densely forested area in southeastern Latvia near Zaborje. It is calm and quiet – the loudest noise is birdsong. No traffic disturbs the small country road lined with pine trees that leads to what is known as the “friendship mound” at the border with Russia and Belarus, until suddenly the way is blocked by anti-mobility barriers.

First come interlocking concrete blocks resembling giant Lego bricks, then metal ‘hedgehogs’ and pyramid-shaped concrete obstacles called ‘dragon’s teeth’. At the end of the road there is a high metal fence reinforced with coils of razor wire. Beyond that again the two red and white barriers at the road over the Zilupe River that runs along the border can be seen. But there is no gate in the fence and the barriers will no longer go up. The friendship is over at this point where the Latvian, Russian and Belarussian borders meet. “Stop! State border” warns the orange sign in three languages placed next to the fence, not far from which an anti-tank ditch has been dug on the Latvian side.

Border guards and obstacles at Latvia’s border with Russia

Photo: Alexander Welscher

It’s a similar sight at many other places along the eastern border of Latvia and in neighbouring Estonia and Lithuania – whose borders are also the EU’s external border. In the wake of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the Baltic States have started to fortify their frontiers to deter Moscow from considering a potential military attack, supplementing existing or yet-to-be-built metal fences with obstacles and barriers based on historical precedents from previous wars in the region and inspired by current techniques used by Ukraine to fend off Russian attacks.

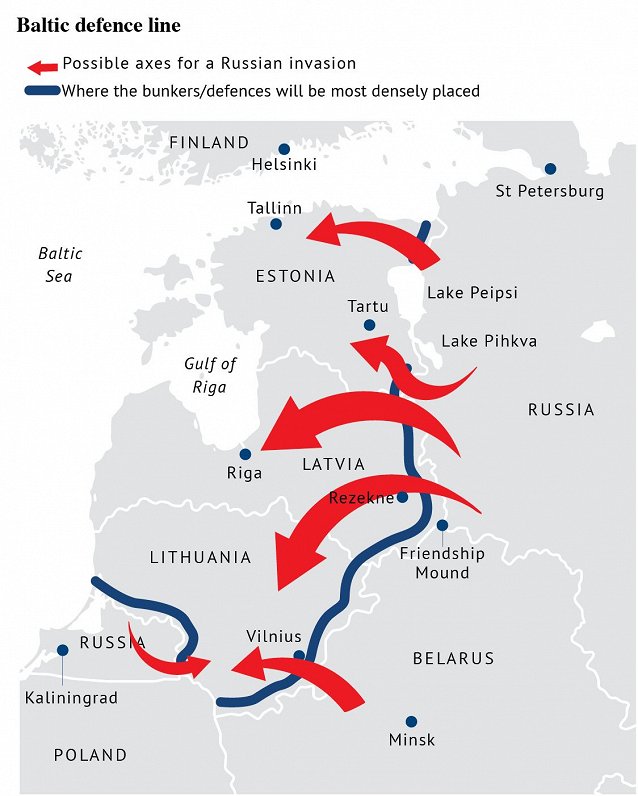

The measures are part of the strategic Baltic Defence Line, which aims to enable a rapid and effective response to an attack and create the conditions for a rapid deployment of mobilised forces. When it is complete, the line will stretch across large sections of the borders of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania – from the mouth of the River Narva in the East to the Russian exclave of Kaliningrad in the West. The Baltic Defence Line is also being coordinated with Poland’s equivalent defensive line codenamed East Shield, to avoid leaving any gaps and to ensure a continuous front at NATO’s eastern flank against any potential Russian aggression. The total cost is hundreds of millions of euros, with the Baltic States and Poland turning to Brussels to help fund the bill.

Readiness is key

“The border as it is now looks fundamentally different compared to two years ago,” Latvian President Edgars Rinkēvičs noted during his visit to the “friendship mound” in late August, going on to say that more remains to be done, in terms of adding sensors and surveillance cameras to the fence, and to installing concrete obstacles and anti-tank barriers all along the 400 kilometre Latvian border with Russia and its authoritarian-ruled close ally Belarus, which hosts troops and nuclear weapons from Russia and made its territory available to Russian forces to invade northern Ukraine.

“Seeing what is happening in Ukraine, we must be ready for all scenarios, at least in the next few years,” Rinkēvičs emphasised to the media representatives accompanying him on his trip, adding that border security is the first line of defence, which must be strengthened every day – with people, technology and infrastructure.

“The fence acts as a deterrent to some extent, but it is not a panacea – systems and border guards are needed,” the Latvian President said, standing at the “friendship mound” where security had been light for a long time.

Dressed in military uniform instead of his usual suit and protected by special military units, the Latvian head of state inspected how the infrastructure at the eastern border is coming along and was briefed on plans for fences, concrete barriers and anti-tank obstacles together with Latvia’s Chief of Defence Kaspars Pudāns and Chief of the State Border Guard Guntis Pujāts.

Rinkēvičs and his entourage were walking along the border and chatting with personnel who guard Latvia’s border with its aggressive neighbours and monitor what is happening over the border. Later on, the delegation also visited an engineering park in Zilupe where counter-mobility elements are stored before being erected on both state- and privately-owned land. Similar sites have also been set up in Estonia and Lithuania to house the various obstacles to be used in defence.

Closely coordinated construction

Plans to build the Baltic Defence Line were first announced at a meeting of the Baltic Ministers of Defence in January 2024, and work on the first ditches, bunkers and embankments started a few months after that. The protective installations are intended to slow down any potential land-based attack from the beginning to enable the armed forces to defend the country and its population from the very first centimetre, even though there is no imminent military threat at present. But readiness is key and peacetime is the best time to prepare such measures, as defence officials in Tallinn, Riga and Vilnius point out.

Supporting NATO’s new forward defence concept and aligned with the alliance’s defence plans for the region, preparation also involves improving the civil protection system and the resilience of the population, not least because credible deterrence against Russia will depend not only on military power but also on social unity. Across the Baltics, governments are pushing the concept of total defence to mobilise the whole of society to defend against military and non-military threats.

Border defences under construction in Estonia

Photo: Estonian Center for Defence Investments

Measures include public information and training on how to deal with crises and war, as well as large-scale military exercises, the activation of reservists and the reintroduction of compulsory military service. Hardening the border also involves instilling the civilian population with a sense of urgency about the security risks and threats they are confronted with at the country’s external border. Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania have closed several border crossings and strongly advise against all travel to Russia and Belarus, with officials warning of recruitment attempts by security services coercing travellers to conduct espionage activities. Unjustified detention, prosecution and even imprisonment may be possible, say the authorities, highlighting the “specific risks” that citizens have been exposed to when travelling to neighbouring countries.

‘The terrain is our advantage’

In developing the defence line, the Baltic States are guided by the lessons of the war in Ukraine. However, the capabilities and geographical conditions of the three neighbouring states are also taken into account.

“The terrain is our advantage – we decide where the fighting will take place in an emergency,” said Latvian military leader Kaspars Pudāns, highlighting that clearly visible fortifications and defensive structures are not just about stopping an invasion, but about shaping the battlefield and forcing the enemy to make predictable movements into areas where resistance and defence are easier. The military logic behind this is to delay, redirect and expose the attacking forces to make them easier targets and allow the defending side to dictate the terms of engagement.

While the execution differs in each Baltic State, the infrastructure is being expanded in a targeted manner – with a clear focus on border security and counter-mobility measures. The aim is to maximise deterrence, not least because of the exposed geographical location of the Baltics States on NATO’s eastern flank. Combined, they share a 1,360-kilometre border with Russia and Belarus. The Baltic States’ only land border with another EU member state runs through the so-called Suwalki Gap: a 70 kilometre-long, narrow strip of land along the Lithuanian- Polish border, sandwiched between Kaliningrad in the West and Belarus in the East.

Baltic Defence Line

Photo: Baltic Business Quarterly

A theoretical Russian advance there could cut off the Baltics from the other NATO countries. Some media outlets have thus dubbed the hard-to-defend corridor “NATO’s Achilles heel” or even “the most dangerous place in the world”.

Several sections of Lithuania’s border with Russia have already been fortified. The country’s military has set up permanent counter-mobility measures and blocked the bridges linking it with Kaliningrad. Among them is the Queen Louise Bridge over the Nemunas River, where on the Russian side a Z sign – the symbol of the Kremlin’s war against Ukraine – is clearly visible on the front of a building facing Lithuania.

Next to the bridges, additional barriers have been formed at places suitable for crossing the river. Engineering structures for securing explosive materials will also be built on the bridges to prepare them for easy demolition in accordance with military plans that were sketched out recently in a more ambitious series of layered fortifications.

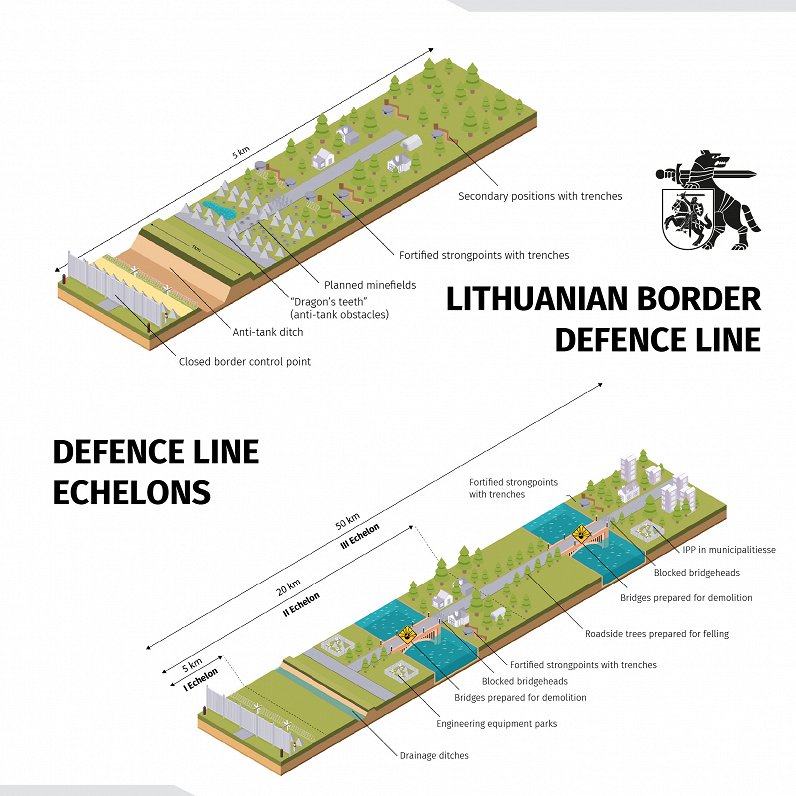

Multiple-echelon defence line

Lithuania has opted to create a comprehensive three-level defensive border line consisting of tank barriers, minefields and fortified positions with strongpoints for defending infantry, reaching a depth of 50 kilometres. Taking the form of three “echelons” and stretching far enough inland to cover Vilnius, the new scheme will give “greater depth, stronger control and full NATO/EU integration at our frontier,” the Ministry of Defence announced. In parallel, Lithuanian cities are also preparing their defences and have pre-positioned counter- mobility infrastructure designed to obstruct key access routes in the event of an attack. This should not only act as a signal to Russia and Belarus but also as a way to immediately protect areas that could be vulnerable.

Lithuanian border defence line

Photo: Lithuanian Ministry of Defence

The Lithuanian military has also already installed defensive structures at disused roads at border checkpoints with Russia and Belarus. “We are starting from the tactical level – with specific obstacles on the border. And later we will combine the entire engineering scenario into a single conceptual system,” Lithuanian military chief Raimundas Vaikšnoras explains the approach that aims to protect against military and hybrid threats. It will be linked at the military operational level to the projects of the other Baltic countries.

Latvia’s new anti-tank fortification efforts also aim first and foremost to secure and protect the country’s weak points along the border. Work on the most vulnerable sections is progressing according to plan and in some sections even slightly ahead of schedule, Rinkēvičs indicated during his border visit, but legal issues such as the compulsory purchase of property and compensation for private landowners still need to be resolved.

The Latvian head of state also called for an expansion of the border zone from the current 12 to 42 metres. This step would be necessary in many situations to help both defence and law enforcement personnel to carry out their duties effectively, he said.

Unlike Latvia and Lithuania, Estonia borders only one hostile neighbour in the East and features natural barriers on its border with Russia – namely Lake Peipus and the Narva River. These bodies of water make much of the border in the Northeast and Southeast of Estonia unsuitable for military movements.

Explosive decision

All three Baltic countries also intend to deploy mines along their borders with Russia and Belarus as part of the Baltic Defence Line. Together with Finland and Poland, the Baltic States are withdrawing from the Ottawa Treaty in order to be able to restart the production and storage of anti-personnel mines near the border. This controversial step has sparked concerns and criticism among international human rights groups who have warned that such mines could pose risks to both soldiers and civilians for decades to come.

Pudāns and other Baltic military leaders, however, consider them essential to form a serious defensive line and argue that the mines would only be deployed quickly in case of emergency; that is, to inflict such heavy losses on the advancing enemy that it would refrain from a prolonged war.

Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania have repeatedly emphasised that they will continue to adhere to international law and the protection of the civilian population despite their withdrawal from the Treaty. All three countries hope to contain risks by mapping their minefields and using remote mine-laying systems to develop the Baltic defence line, which is a means to confine crossfire to a belt along the border already sacrificed for defensive depth since the three countries lack areas to which the armed forces could retreat and regroup should fighting break out.

Dual benefit: border security and migration control

Dispersed across the border area, all defensive installations will have a dual use in supporting border surveillance during peacetime. The anti-tank barriers and ditches will make illegal border crossings more difficult – and thus contribute to national security in dealing with third-country migrants from Belarus who are deliberately and systematically pushed to the border at Minsk’s behest in order to put pressure on the West and destabilise the societies of EU countries.

This has made the eastern border a migration hotspot and provoked a border crisis in 2021 that led to a ramping up of the external security infrastructure, the closure of border crossings and restricted access to the border area requiring special permits.

Describing the current situation on the eastern border, the Chief of the State Border Guard of Latvia Guntis Pujats said that it remained “tense but stable”. Latvia continues to be a target country for illegal border crossers and day- to-day border monitoring remains necessary and relevant, he said during the border visit.

Lithuania-Belarus border

Photo: Lithuanian Armed Forces

The situation at the Lithuanian border with Belarus is much the same, while Estonia has so far been spared the kind of organised large-scale migration crisis that its neighbouring countries have experienced. Finland was also affected for some time, when, at the end of 2023 it registered a sharp increase in the number of migrants arriving at its border from Russia and trying to enter the EU without proper documentation.

Reacting to migration pattern changes, Estonia has strengthened protective measures and installed gates and roadblocks at the country’s three remaining border crossings with Russia. These barriers can be closed within seconds if necessary to stop the movement of people and vehicles.

Similarly, the border strips are kept clear not only for military purposes, but also for the border police, which has been on high alert and has stepped up border surveillance to ward off illegal migration. In a show of support and solidarity, the Baltic countries were helping each other and dispatching units to the sections of the border most affected, and the European Border and Coast Guard Agency Frontex has also increased its presence in the region.

‘Drone wall’

While work on the physical barrier is already in full swing in many places along the eastern border, military officials and other experts are also drawing attention to security threats posed by recent airspace violations by drones, emphasising the need to strengthen airspace surveillance systems and anti-drone capabilities.

“We have to explore ways to use all the latest technologies when it comes to border security,” EU Commissioner for Defence and Space Andrius Kubilius said recently during a visit to his home country, Lithuania. “In my view, the creation of a drone wall must be included in any such plan,” the EU official emphasised, adding that such a wall is “no less important than a physical border.”

The idea of a Baltic ‘Drone Wall’ was first floated last year as part of a greater endeavour encompassing the entire eastern border and stretching from Norway to Poland. While details such as funding, timeline and technical aspects of the ambitious project are stillunclear, calls for rapidly developing drone and counter-done capabilities have intensified following several incidents involving drones.

Both in Latvia and Latvia unmanned Russian drones carrying explosives crossed into their airspace from Belarus before crashing, while in Estonia an off-course Ukrainian combat drone went down. There have also been similar cases in Poland, Romania and Moldova.

The drone wall concept responds to a changing battlefield where conventional complex weapon systems are increasingly being replaced by drones. Ukraine relies strongly on drones in its defensive campaign against the Russian armed forces, who in turn are using the unmanned aerial vehicles on the front line.

Drones also pose a rapidly evolving threat across NATO’s eastern border, which also needs to be hardened against Russia’s unconventional tactics and repeated acts of sabotage, such as drone incursions, GPS jamming and cross-border provocations. Some even consider this to be more urgent than setting up physical barriers for a theoretical Russian attack on the Baltic States, not least because these are not isolated incidents but systematic actions.

Rinkēvičs also pointed out that securing the border is an all-encompassing and permanent task, requiring continuous work and attention both from the military and the border guards. “Strengthening the border does not mean implementing anti-mobility systems and then forgetting about them,” the Latvian President emphasised at the end of his visit to the eastern border, adding that it must be constantly improved and developed.

“This preparation and additional work – combined with the presence of NATO soldiers – are what, I hope, will make any potential aggressors think twice about what they should do or, better, not do.”

NOTE: This feature first appeared in Baltic Business Quarterly and is reproduced by kind permission of the author and AHK, the German-Baltic Chamber of Commerce in Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania.