Until about a decade ago, the metropolitan Germans may have been right about the Black Forest. In 2010, Gallus Strobel, the mayor of Triberg (where Germany’s highest waterfall, the Gutach, cascades) was brutal about the region’s need to play tourism catch-up, describing his town as sleepwalking into the future. Visitor numbers were plummeting and younger residents were moving out. Luckily, things have transformed. Culinarily, culturally and, in this era of threatening climate change, even existentially, the forest is calling again. A wave of chefs, food producers, entrepreneurs, hoteliers and creatives are returning to their homeland: the big buff-up has begun.

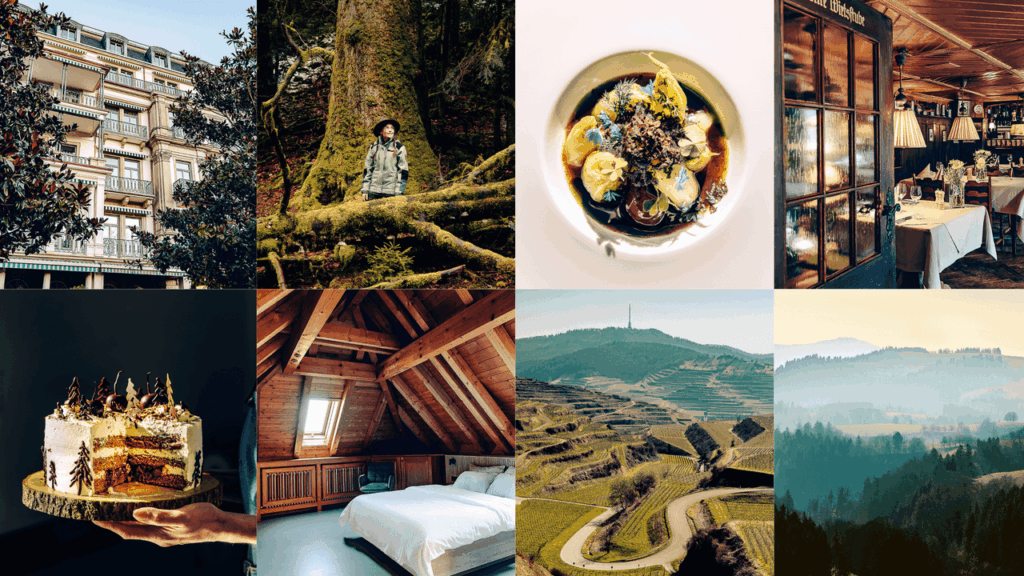

The Black Forest’s long-standing history of rich haute cuisine is famously garlanded: there are 31 serious restaurants and 40 Michelin stars. But while gastronomic excellence is not news in the forest, future-facing plates are now creeping onto traditional menus. In the south, the valley of Münstertal is the Black Forest spot from central casting, blessed with a mild climate, picturesque farms and the contented grazing of cows. It’s also the childhood home of Viktoria Fuchs, who, though still only 35, is one of Germany’s most well-known chefs. After training under Douce Steiner at Sulzburg’s two-Michelin-starred Hirschen restaurant, she worked at Le Canard in Hamburg, Rüssels Landhaus in the Hunsrück mountain range near Luxembourg, and Luce d’Oro (now Ikigai) at the famed hotel and retreat Schloss Elmau in the Bavarian Alps. But she describes herself as “the homesick type” so, eventually, she returned to the historical Romantik Hotel Spielweg, a Münstertal institution and home to her family’s business since 1861. A few years ago, her sister took over managing the hotel and Fuchs and her husband, Johannes Schneider, started running the kitchen. The rest is recent history: they’ve since been awarded a Michelin Green Star.

Fuchs and Schneider deliver the Black Forest classics – black pudding brägele, a fried potato dish; and sauerbraten, a marinated meat roast – but also dishes that throw out the rule book, including wild boar dim sum and venison vitello (as opposed to the traditional veal) from their hunting grounds. “We don’t want to wander too far from the path of tradition, but we’re also eager to try something new,” says Fuchs, sitting in her dark grey chef’s jacket at the table in the family dining room, surrounded by century-old timbered walls and ceiling (modernity incurs in the adjoining sitting room with its dark green walls and leather sofa).