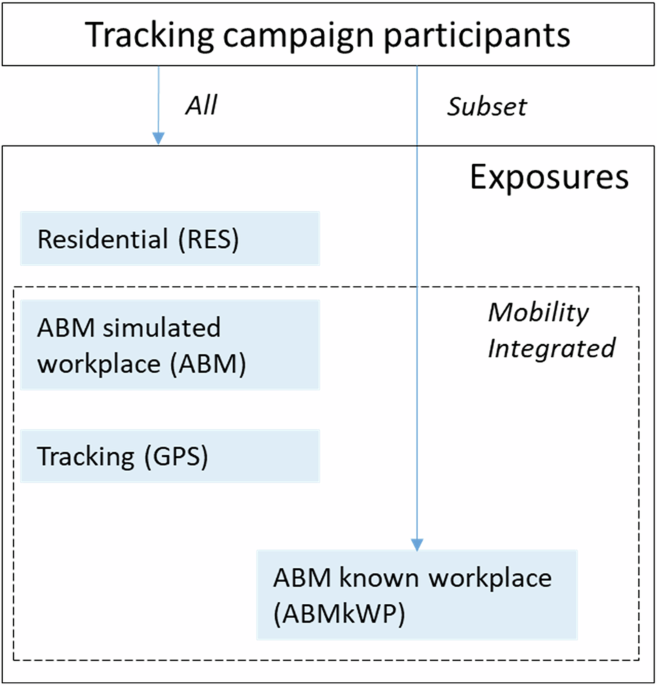

We compared air pollution exposures based on the residential address with mobility-integrated air pollution exposures for almost 700 subjects in two tracking campaigns. For mobility-integrated exposures, we modeled exposures using ABM and assigned exposures as determined by the movements of individuals collected using the tracking data. In both tracking campaigns, conducted in two different study areas, very strong correlations were found between annual average residential exposure and mobility-integrated exposure for NO2 and PM2.5, both based upon observed tracking activity data and modeled ABM activity data. Furthermore, based on the same underlying air pollution data, the exposure levels—determined by the routes and time spent in specific locations—were very similar between both approaches. We did find a slightly smaller exposure contrast for ABM exposures (e.g., IQR = 4.93 µg/m3 for NO2 in NL; 11.03 in CH) compared to RES exposures (e.g., IQR = 5.93 µg/m3 for NO2 in NL; 13.94 in CH) (see Table 3). This can be explained by the phenomenon that subjects living in residential locations with high concentrations have a high probability of working in areas with lower concentrations and vice versa. Finally, we found that the residential exposure also correlated well with the mobility-integrated exposure based on actual time activity data in the tracking population.

Exposures estimated from tracking and ABM with known and simulated workplace

The two approaches used in this study, ABM and tracking, differ in multiple aspects. ABM is a modeling approach that can be applied to large populations. As ABM is based on large-time activity surveys, it is more representative of the total population than tracking studies. ABM, however, makes assumptions about activity patterns, e.g., that activity can be represented by a simple standard pattern (for weekdays, for weekend days), neglecting short-time variations. It also assumes that within “profiles”, activities are comparable between individuals. Tracking relies on actual measurements and can therefore only be applied for short periods in smaller populations. When tracking is used for estimating long-term exposures, we must assume that the activity over the duration for which tracks are available is representative of the long-term activity of individuals. It is likely that actual tracks over a year would show substantially more variation than what is measured over a short time span, but the general pattern of activity (home, work, commute/on roads) is possibly quite well represented. In both approaches, sensitive populations like the ill and elderly are likely not well represented; however, as these people tend to stay more at home, we likely underestimate the correlation for these groups.

The high correlation between tracking and ABM-based exposures supports the use of ABM modeling in large populations. The Bland-Altman plots comparing these exposures were very stable for both pollutants in the two study areas, meaning that the tracking and ABM-based concentrations were similar. However, the Bland-Altman plots do show a bias in that participants of our tracking campaigns residing in areas with relatively low ambient air pollution may experience elevated mobility-integrated exposure due to an increased likelihood of commuting to or working in regions with higher pollution levels. Conversely, participants residing in highly polluted areas are less likely to travel to environments with significantly higher pollution concentrations, resulting in comparatively lower total exposure when mobility is accounted for. For our study areas, however, we can conclude that air pollution exposures derived from the tracking campaigns were successfully modeled with ABM, which used information commonly available in cohorts and larger administrative cohorts (e.g., age, sex, socio-economic status and employment status). The lack of a gold standard for evaluating long-term personal exposure to outdoor-generated pollution complicates the assessment of how well the three exposure measures reflect true personal exposure.

ABM with simulated work location exposures, by design, also has more uncertainty compared to ABM with known work location. In addition, differences with residential exposures are smaller for ABM with a simulated work address. In general, ABM with a known work location is preferable and collecting work location data in cohort studies is advantageous. The high correlation between the two ABM approaches and the good correlation with tracking-based exposures, however, suggests that ABM with simulated work addresses provides a reasonable approach to estimate exposure beyond residential address in studies that do not have known work addresses.

Comparison with previous studies

Our observations are in line with several previous studies comparing residential and mobility-integrated exposures [13, 14, 34,35,36]. In all these studies, agent-based modeling was conducted using time surveys. Setton and co-workers documented that the agreement between residential and mobility-integrated exposure diminished with increasing time at work and with increasing distance between home and work locations [36]. A recent study using tracking data also reported high correlations for noise and PM2.5 [20]. Other studies have performed comparisons without ABM, thus based solely on exposure determined at the residential address location (home) vs. exposures including work address (work) and/or during commute. A study in Basel, Switzerland, compared exposure at the residential address with exposure whilst commuting and at the work/school address [14], indicating that, while there is room for improvement, it is reasonable to use exposure characterized at the residential address. A study in Montreal, Canada, showed that almost 90% of individuals had a lower 24-h daily average NO2 estimated at home compared to a mobility-integrated NO2 exposure [37]. Researchers in the Netherlands followed 269 adults with a GPS-enabled App for 7 days and compared the residential exposure only with a mobility-integrated PM2.5 exposure, concluding that the residential exposure was a good proxy for overall exposure to outdoor air pollution [20]. A study in Shenzhen, China, used cell phone data from more than 300,000 individuals to assess the impact of mobility on air pollution exposure. They concluded that while mobility impacted exposure on the individual level, it did not significantly impact exposures at the population level, in particular for larger studies [38]. A study in the UK compared population-weighted NO2, PM2.5 and O3 exposures at the residential address only with a combined residential and work exposure. They used a chemistry transport model to estimate rush-hour specific long-term averages and found only a small increase in population-weighted NO2 and PM2.5 exposures when including the work location (2 and 0.3%, respectively) [39].

Few studies have applied ABM to assess mobility-integrated air pollution exposures. Lu et al. used ABM to estimate exposures to NO2, incorporating work location and commuting patterns for the population of the city of Utrecht, the Netherlands. They found very high correlations between residential and mobility-integrated exposures (R2 > 0.93) [40].

Only a few studies were able to compare personal air pollution measurement data with residential and mobility-integrated exposures. Recently, Wei et al. compared personal measurements of PM2.5 and BC for 41 adults in the Netherlands with modeled home-based and mobility-based exposures [41]. They found that mobility-based exposures better represented personal measurements compared to home-based exposures, and that adjusting for the indoor-outdoor ratio was more important than adjusting for travel modes in improving the exposure assessment. A challenge in all direct personal monitoring studies is to assess individual long-term exposure and separation of indoor and outdoor sources. For acute health effect studies, direct personal exposure monitoring has been applied more often [42].

A recent review of air pollution exposure studies comparing residential and mobility-integrated exposures evaluated a number of epidemiological studies that compared health effects using the two approaches to evaluate exposures [17]. They found that the agreement between residential and mobility-integrated exposures was generally high (R > 0.8).

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this is the largest study in terms of participants (n = 686), collecting 2 weeks of tracking data with detailed time activity. This allowed for a robust comparison between a number of approaches to determine exposures (residential, mobility-integrated with and without known workplace, real-time activity patterns) and to perform a thorough evaluation.

We conducted the tracking campaigns in two countries, broadening the applicability of our findings to similar demographic and geographical settings.

The participants of the tracking campaigns in both countries, however, were not representative of the full Swiss or Dutch populations, with overrepresentation in the 40–60 year old, higher education, high income and full-time worker groups. The overrepresentation of highly educated participants in the tracking study populations is in agreement with most exposure and epidemiological studies involving invited participation. Participants in both tracking campaigns also resided in more urbanized areas compared to the national population. The travel survey data, which we used to inform the ABM, were, however, specific to each country and more representative, which, given the high comparison between ABM and tracking, suggests that our tracking populations were not too unrepresentative.

Our findings apply to long-term air pollution exposure; we did not evaluate the impact of mobility on short-term exposure estimates. Our findings further apply to the studied pollutants, specifically NO2 and PM2.5. As NO2 is often considered a surrogate for traffic-related pollution, we suspect that qualitatively our findings apply to other traffic-related pollutants. If the spatial pattern of the pollutants differs substantially, however, results may be different.