“Not a single clause or word which says anything about supplier liability,” said Congress MP Manish Tewari in Lok Sabha. His peer Shashi Tharoor added, “A supplier, who has provided faulty equipment, walks away without any liability and Indian tax-payers are made to bear the brunt”.

The newly passed Sustainable Harnessing and Advancement of Nuclear Energy for Transforming India (SHANTI) Act, 2025 has made drastic changes to liability laws in case of nuclear accident — exempting suppliers (foreign or domestic) from any statutory liability, while capping the liability of nuclear plant operators to ₹3,000 crores.

‘SHANTI’, which replaces the two existing laws governing India’s nuclear sector — the Atomic Energy Act, 1962 and the Civil Liability for Nuclear Damage Act, 2010, has now become an Act after President Droupadi Murmu gave her assent on December 21. The Bill was passed through both Houses on December 17, 18, after the Centre refused to refer the Bill to a Parliamentary Standing Committee for further scrutiny.

Opposition MPs, lawyers, nuclear scientists have pointed out the pitfalls of the Act such as – single composite licence for several processes, statutory vacuum, absence of long-term radioactive waste management plan, restricted information and dilution of civil liability in case of nuclear incidents/malfunction.

What does SHANTI say on civil liability?

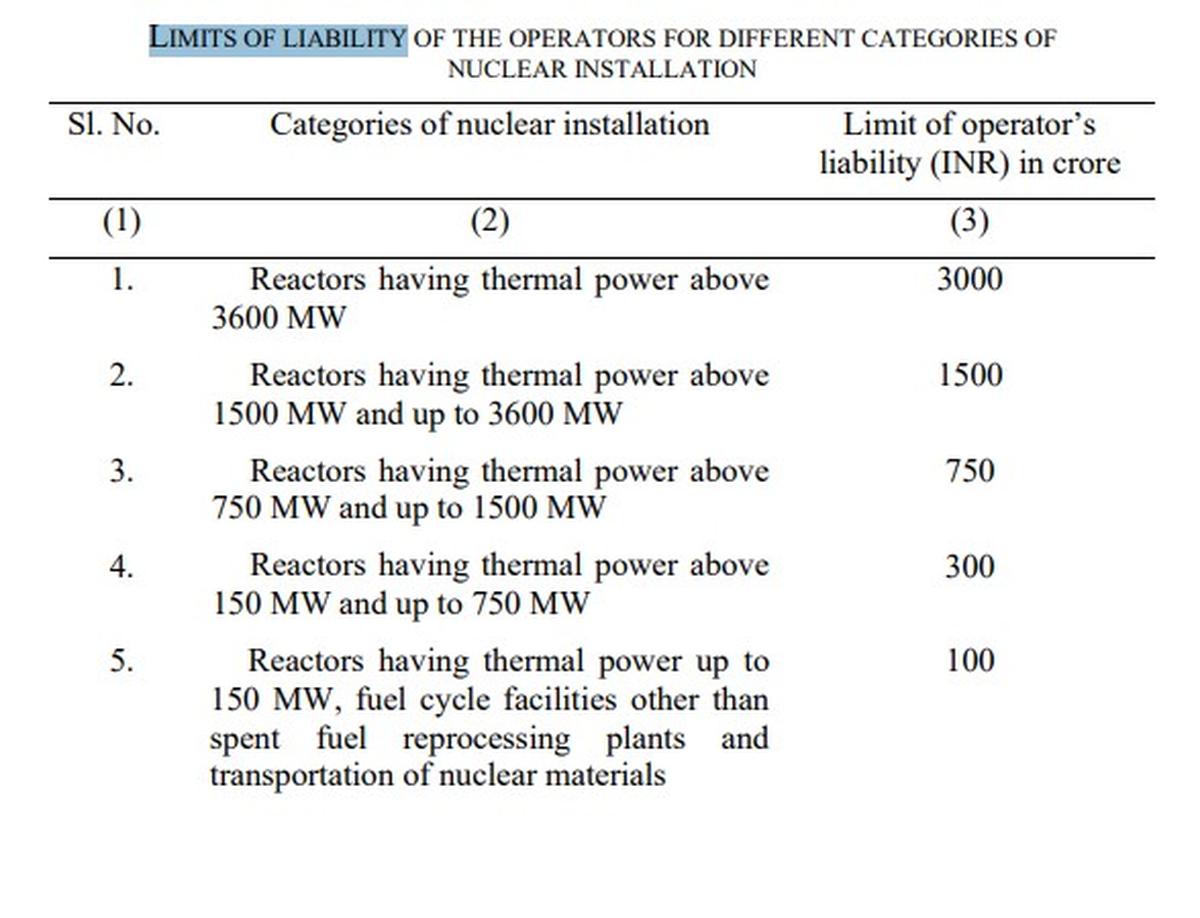

The Act holds the nuclear plant operator responsible for any incident that occurs during either installation, transport of material prior to installation and after. The operator is held responsible for any loss of life, work, injury, damages. However, the limit of liability on these operators is capped at ₹3,000 crore in case the installed capacity of the nuclear plant is above 3600 MW (mega-watts). For a nuclear plant with a capacity less than 150 MW, the liability is set at ₹100 crore. If the liability exceeds the upper limit, the Centre will bear the liable.

It also exempts the operator from any liability if the incident occurs due to a natural disaster, armed conflict, hostility, civil war, insurrection or terrorism. The operator is also not held liable if any damage is suffered by a person on account of his own negligence. In all such exemptions, the Centre will take upon the liability. Any plant can also be exempted from liability if the risk involved is deemed ‘insignificant’ by the Centre. There is no mention of supplier in the entire Act, exempting them from any liability or punitive action under this law.

“The liability of the Fukushima disaster in Japan is about $200 billion and it is likely to go up,” said Dr. E.A.S Sharma, former Principal Adviser (Energy), while speaking to The Hindu. He adds, “Imagine if your actual liability is about three lakh crores, and then what is the use of having a cap of three thousand?”.

Defending the graded liability in Parliament, Union MoS Jitendra Singh said that it gives a level-playing field so that ‘participation is possible at every scale’. He claimed that by putting higher liability on large reactors and lower on small reactors, SHANTI ensures fair risk-sharing, responsible participation and a safety-first approach.

“Irrespective of this (lower installed capacity), when an accident takes place, it can be like an atom bomb. Almost up to 30, 40 miles, you know, it can affect people’s health and there will be radioactive contamination,” counters Dr. Sharma. He says use of substandard material in nuclear reactors and design defects are very common in the global nuclear industry.

Bumper cars in abandoned Pripyat, Ukraine in the largest city in the exclusion zone surrounding the Chernobyl reactor, April 9, 2016. Thirty years later, there are signs of commercial clear-cutting in supposedly off-limits forests around the site of the nuclear disaster in Ukraine. Photo: The New York Times

Senior advocate Prashant Bhushan warns that such a low liability cap can create an incentive to suppliers and operators to cut corners. “The Supreme Court has laid down a principle that if you are operating a hazardous industry, then you are absolutely liable to the full extent of the damage. When your liability is capped at such a ridiculously low amount, it contravenes Article 21 – the Right to Life. You are endangering the life of the people, and you are virtually exempting the supplier and the operator,” says Mr. Bhushan.

Highlighting the strain the additional liability will place on Centre’s budget, Dr. Sharma adds, “Previously, NPCIL was the only operator and now private players will be there. One nuclear accident like Fukushima, can take away 1/3rd of the budget expenditure for a year. You will not have any money for your social justice schemes, education, health, infrastructure, crippling India’s finances”.

Who holds the operator liable?

“When Fukushima took place in 2011, under public pressure, the Department of Atomic Energy introduced a bill to constitute an independent nuclear regulatory authority. This Bill went to the Parliament Committee which made some very far-reaching suggestions to strengthen the autonomy of the regulator. Surprisingly, after that, Department of Atomic Energy just remained silent. Now after 13 years, SHANTI has constituted the Atomic Energy Regulatory Board (AERB), but does not make it independent,” explains Dr. Sharma.

Under SHANTI, the AERB is a seven-member board with all appointees made by the Centre, sapping any semblance of independence from the body. This Board sets limits of radiation exposure to the workers and the public, limits for radioactive releases and discharges to environment, sets safety standards in all aspects of operation, working conditions, transport, waste disposal etc.

It also grants safety authorisation, regulates nuclear facilities, advises the Centre on safety, radiological surveillance and preparedness in response to nuclear emergencies. In case of a nuclear incident, the AERB will provide its recommendations within fifteen days from the date of occurrence of such nuclear incidents for notifications. The Board can exempt any radioactive material or any radiation generating plant from the requirement of safety authorisation.

“It (AERB) is subordinate to Department of Atomic Energy and they are supposed to regulate the department’s nuclear facilities?” questions Dr. Sharma. While the Act does not allow any civil court to entertain any suit which falls under the AERB, Centre and Appellate tribunals’ jurisdiction, the High Court and Supreme Court can intervene, clarifies Mr. Bhushan.

“The Act compromises Make in India and gives access to foreign players to all this nuclear and fissionable material. Suppose there is some negligence and it (nuclear material) gets into terrorists’ hands or it happens deliberately, a nuclear disaster can happen. This Act is a complete sell-out to foreign companies and to Adani, compromising the country’s safety, security and sovereignty,” concludes Mr. Bhushan.