They land not far from the Bulgarian border.

What are you supposed to think when you wake up in the middle of the night to the deafening noise of Antonov aircraft flying over Niš, while at the same time the flight officially does not exist on Flightradar24 — the global flight-tracking network that shows live air traffic from around the world?

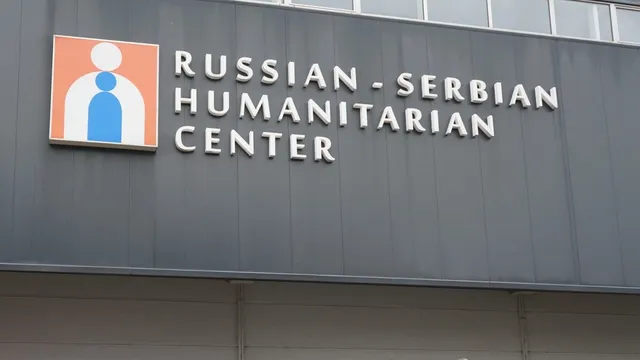

This was said by the well-known sociologist and journalist Olivera Sašek Radulović in connection with developments at the “Serbian-Russian Humanitarian Center” in the city of Niš, about 100 kilometers from the Bulgarian border, BGNES reported.

On December 25, the parliamentary groups of the Movement of Free Citizens, the Party of Democratic Action of Sandžak, the Party of Democratic Action, and the Green-Left Front submitted to the Serbian parliament a draft law declaring invalid the Agreement between the Government of Serbia and the Government of the Russian Federation on the establishment of the “Serbian-Russian Humanitarian Center.” According to the sponsors of the bill, “citizens and institutions in Serbia must know what is being done at this center in Niš, who finances it, and how its existence affects the country’s position in the international community.”

“Citizens and institutions must know what is happening there and who finances it. Instead, in Niš we have remained silent for many years about this center. What are you supposed to think when you wake up in the middle of the night to the deafening noise of Antonov aircraft over Niš, while at the same time the flight officially does not exist on Flightradar24 — the global flight-tracking network that shows live air traffic worldwide? Anything is possible, because the public is regularly deprived of information about why the largest Russian aircraft has landed at Niš airport and what cargo it is carrying,” Radulović asked in an interview with Danas.

She said that it is necessary to start a public dialogue about the Center’s activities over the past 13 years. “What assistance has it provided during floods, fires, and other emergency situations? I believe there are objective data that could provide a clear picture of this assistance. Depending on its scope, we should assess whether we need the work of such a center or not, especially considering the extent to which Serbian citizens finance its operations, because as far as I know, this issue is not discussed at all,” Radulović said.

According to her, an assessment is also needed of how the existence of the Russian center in Niš affects Serbia’s foreign-policy position, above all its relations with the European Union.

“And when the Center is examined from these perspectives, I think it will not be difficult to reach a conclusion based on common sense, rather than on the stereotype that Russians are our brothers,” Radulović added.

BGNES recalls that, in the very heart of the Balkans, there is what is officially termed the “Serbian-Russian Humanitarian Center.” It is located in the city of Niš, about 170 kilometers from Sofia. Its purpose remains unknown to this day.

Two main elements play a central role here: the “Serbian-Russian Humanitarian Center” itself and the direct deliveries of Russian weapons, including modern Pantsir-S air-defense systems, MiG-29 fighter jets, and modernized tanks. On October 20, 2009, Russia and Serbia decided to cooperate in emergency situations related to natural disasters, technological accidents, and the mitigation of their consequences. Three years later, on April 25, 2012, the center became a reality after the signing of a bilateral intergovernmental agreement. It was signed by Serbia’s interior minister and Russia’s minister for emergency situations, General Sergei Shoigu — later minister of defense, one of the architects of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and one of President Vladimir Putin’s closest associates since 1999. The Center’s statute was also adopted alongside the agreement.

According to this statute, the Serbian-Russian Humanitarian Center is an intergovernmental humanitarian non-governmental organization. It is registered in Serbia in accordance with Serbian law. The Center is intended to be “a fully fledged international structure providing assistance and support in emergency situations to all countries in the Balkan region.” Any state or organization that shares its goals and tasks may join it. The Center is headed by a director and a co-director, appointed respectively by the Russian and Serbian sides on a rotating basis for two-year terms.

Because of the secretive nature of the base near Niš, it has repeatedly been the subject of criticism from the West. In early 2017, U.S. Deputy Assistant Secretary of State Hoyt Brian Yee openly stated during a meeting with President Aleksandar Vučić that Washington was “concerned about what the Serbian-Russian Humanitarian Center in Niš could become.”

Around the same time, U.S. Ambassador to Belgrade Kyle Scott warned: “I don’t know exactly what they are doing there, but in my view there are sufficient reasons for concern.” After warnings from the EU that the existence of the Center could hinder Serbia’s accession negotiations with Brussels, Vučić said on June 17, 2017 that Serbia would decide for itself what to do regarding Russia’s request for its personnel to receive diplomatic status. On November 15, 2017, the commander of U.S. Army forces in Europe, General Ben Hodges, said about the Center: “I do not believe this is a humanitarian center. That is the facade, but that is not its purpose. There should be much more transparency, and I would welcome an invitation to visit it.”

The Center is located in immediate proximity to Niš Airport. This raises questions about possible Russian-Serbian military exercises conducted near the Center and through the Batajnica military airbase near Belgrade. The Serbian-Russian Humanitarian Center in Niš was opened in April 2012, at a time when Russia’s minister for emergency situations was Sergei Shoigu, who created and led this militarized ministry for more than twenty years before becoming Russia’s defense minister.

At a meeting in May 2021 with Serbia’s interior minister Aleksandar Vulin, Yevgeny Zinichev — former deputy director of Russia’s Federal Security Service — stated that the Center is the only and the largest of its kind in the Balkans. Russia’s ambassador to Serbia, Alexander Botsan-Kharchenko, has called it one of the most important projects between the two “brotherly” countries. It is located at Serbia’s second-largest international airport, Constantine the Great, and if necessary could be transformed into a base capable of controlling territory within a radius of at least 300 kilometers, covering Serbia, Kosovo, Montenegro, North Macedonia, parts of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Romania, and nearly half of Bulgaria. The Kremlin has repeatedly insisted that Serbia grant special status to Russian personnel working at the Center through an agreement on diplomatic immunity, living conditions, and privileges, effectively equating it with a diplomatic mission.

Access by diplomatic representatives accredited in Serbia to the Center remains highly restricted, further fueling speculation about what is happening there. Over its ten years of existence, the Center has participated in fighting forest fires in eastern and southern Serbia and in North Macedonia, but in 2019 the Bulgarian government rejected a proposal from the Center to assist with firefighting on Bulgarian territory. During floods in Serbia, Russian pumping equipment was delivered through the Center, and at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, a chemical-defense unit of the Russian Armed Forces passed through the Center to conduct disinfection in certain areas of Serbia. These activities, along with several humanitarian actions, have been used to justify the need for such a Russian crisis center in the Balkans.

So far, no information has been published indicating that the Center conducts aerial surveillance or reconnaissance over Kosovo, where the largest U.S. logistics base in the Balkans, Camp Bondsteel, is located, or over neighboring countries. Such activities may not be necessary, given that Serbia and Russia exchange confidential data as partner and allied states. Moreover, the likely purpose of the Center in Russian strategic planning is primarily the attractive idea of deploying, if necessary, a military base in NATO’s rear.

After Russia’s aggression against Ukraine, Serbia remains the only country in Europe that refused to support sanctions against Russia, declined to condemn the invasion, and increased air traffic between Belgrade and Moscow. | BGNES