Niccolo Machiavelli and Carl Schmitt are most often regarded as the two crucial modern authors to whom we can attribute our strong concept of the political. Both thinkers present politics as an agonistic struggle for power, and even in certain cases an irreconcilable antagonism between factions. No doubt, modern competitive democracy is itself based on a powerful concept of conflict and rivalry. This is the precondition for claiming that voters will receive well-defined alternative visions of how to handle common affairs, to have real choices. However, it is difficult for everyday thinking to understand why conflict would be necessary and unmanageable in the conduct of the affairs of the political community.

By contrast, liberals often present a kind of apolitical attitude. According to their interpretation, government only has the function of guaranteeing for citizens the preconditions of a free life. Within the liberal framework, therefore, politics has no real relevance in human life. After all, individuals are able to decide for themselves what they want to do alone or in their preferred groups in their free time. There is no need for more government, ready to intervene in the affairs of what is called civil society. This is a basic principle of classical liberalism, confirmed by the concept of civil society since Hegel—and even arguably since the authors of the Scottish Enlightenment from whom Hegel took the notion.

The agonistic politics of Machiavelli and the apolitical liberalism of Hegel are, in fact, two extremes of our modern conceptualisations of the political. And as a good Aristotelian, I would also claim that it is somewhere in between these two opposite extremes that we should look for the right solution to the problem. What is necessary, then, is a third way of understanding modern politics. There is an early modern concept that might mediate in the social crises of the Western world in the twenty-first century: civility. Civility is not a substitute, but a supplement to the institutional safeguards of our constitutional democracies. Civility can be understood as a purely political virtue, the fruit of a practice within a political culture, which can bring together and encourage cooperation between members of different substantial subcultures.

The Politics of Civility

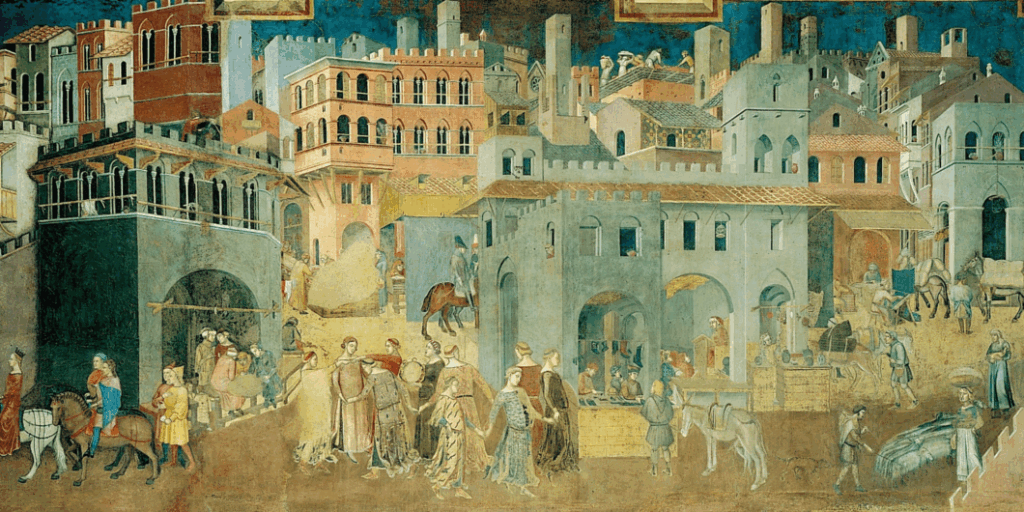

A key to uncovering this third way is the concept of civility. Etymologically, our term “civil” is connected to the Roman terms civitas—city—and civis—citizen. These are the Roman variants of the ancient Greek terms politikos and polis. Rightly understood, then, the ancients did not believe in a fundamental conflict between the political and the civil.

Hegel and his Scottish precursors made the brilliant move to divide the realms of the civic and the political. After the alarming experiences of totalitarian rule, however, as thinkers like Hannah Arendt propose, we should return to a concept of the political, reconnecting (political) civility and the (apolitical) civil. After all, culture is not only connected, but in fact upstream from politics.

Civility depends on a special sort of social skill, which is itself rooted in a mode of being.

How does that insight translate into a via media between the agonistic/antagonistic super-politics and the apolitical liberal concept of politics? I would like to propose thinking about politics as an answer to human coordination problems, based on the assumption that cooperation is made possible by a social virtue: the cultural achievement that we call civility.

Two Aspects of Human Nature

This virtue of sociability, identified as a perfected human propensity, was already discussed by Aquinas. The Thomistic tradition defends a positive view of human nature: human beings have the potential to come into contact with the other, based on the Thomistic features of “compassio” and “concordia”, the sort of fellow-feeling, which belongs to us, in relation to our neighbour, in the Christian sense of the term. This view is the diametrical opposite of the dark, Augustinian notion of human fallibility, which presents the human being as a selfish and self-enclosed being.

To make sense of this apparent contradiction within the Catholic tradition, the most promising choice is not to go for an either-or, but rather to see them as two sides of the same coin, two aspects of the same phenomenon. Human beings are both sociable and fallible creatures, and while sociability allows them to acquire the virtue of sociability, it is their fallibility that makes political institutions still necessary.

Remember that Thomas Hobbes found the Biblical monster, Leviathan, necessary in politics because he had so disillusioning experiences of the human being in the English Civil War (homo homini lupus). Hobbes was an exponent of the antagonism between human groups, introduced, along the lines of pessimistic ancient historians, updated in the early modern context by Machiavelli, and sharpened in later modernity by Carl Schmitt.

Recall also the dedication of Hobbes’s De Cive (a title which refers to our topic, the citizen), where he, too, presents both sides of human nature, but interprets it in a way to point forward to Schmitt’s friend-enemy opposition: “To speak impartially, both sayings are very true; That Man to Man is a kind of God; and that Man to Man is an arrant Wolfe. The first is true, if we compare Citizens amongst themselves; and the second, if we compare Cities.” This way, he implies that cities are necessarily in conflict, which is one of the foundation stones of international relations. This pessimism leads him to the conclusion that we need well-defined institutions to keep those conflicts under control.

Taming Power and Developing the Social Virtues

Ultimately, Hobbes’s solution prioritises the institutional safeguards of the centralised state. This is what his famous Leviathan symbolises. The contradiction in his system is that although he introduces the metaphor of the wolf to describe the conditions of the conflict between the cities, his theory, embodied by the Leviathan, is about a regime of fear and the monopolistic use of power as the basic principle within the state, and not only among the states. In other words, for Hobbes, the agonistic dimension characterises the internal realm of the civitas as well.

A more constructive approach to civility works for the opposite conclusion: civility is here understood as an inbuilt incentive of the human being, which on the long run can humanize interpersonal relationships, and through that the otherwise brutal political relations. Two considerations might help us understand how a humanisation of power can be possible.

The first is an idea worked out by the twentieth-century Hungarian legal-political theorist, István Bibó. He attributed the humanisation of power to the Christian religious-moral impact on the exercise of political power in the 1970s, referring to the medieval and early modern European developments. As a theorist who himself took administrative and even political roles in critical moments in twentieth-century Hungarian history to show that he takes responsibility for what he teaches, Bibó was certainly not naïve. On the contrary, he was a kind of Christian realist. He did not underestimate the importance of institutions; he did not, however, underestimate the achievements of European culture, which helped the development of the cardinal virtues. Bibó, who fought against both the Nazi and the Soviet Communist power in Hungary, was well aware of the dangers of a fallback that Norbert Elias warned about, and that came true in World War II and the Soviet occupation of Central and Eastern Europe.

The second consideration is a widely shared view among the authors of the Scottish Enlightenment: that in the long run, long-distance commerce can help to negotiate international conflicts and prepare the ground for international cooperation. In other words, they believed that commercial activity can result in win-win outcomes for sellers and buyers, and also, therefore, social peace. These authors—Hume, Smith, Ferguson, Robertson, Millar, and others—attributed crucial relevance to the virtue of moderation, which is the necessary virtue to prepare humans for collaboration on a grand scale. The basic idea of these Scotsmen was that a way of life lived in the routine of commercial transactions helps to refine one’s manners and to achieve a civil attitude towards others, including aliens. Business transactions are based on rational calculations, and they prepare the ground for a more rational attitude in political problem-solving, as well. Also, the result of getting acquainted with other cultures is to learn how to communicate and negotiate with foreigners.

The Politics of the Middle Classes

A German-French exchange of ideas after the French Revolution led to the insight that the idea of the “citoyen” in the political sense and that of the “bourgeois” in the economic and social sense (in the sense of the bourgeoisie) are not opposites, but rather are closely related concepts. Taken together, they lead us directly to the concept of civility. As we read it in novels from Zola to Thomas Mann, the material autonomy of the bourgeois can encourage him to actively support his community, and it can even prepare him to take responsibility for the future of his community.

The German notion of Bürgerlichkeit can help us understand this kind of civility. The word expresses more than just the German equivalent of the way of life and consciousness of the English middle class, also well-known from English novels, at least from those of Jane Austen. Having the means for a decent way of life (Besitzbürgertum) should lead the burgher to a way of life defined by culture (Bildungsbürgertum). It also implies the conclusion that commerce, and indeed, private ownership, entails responsibility for community affairs, in other words, economic activity, prepares people for political participation as well. In this sense, the term Bürgerlichkeit has a republican, participatory element, which points back to the ancient Greek and Roman ideas of political participation.

Even if we can’t be good, we should be polite, where politeness “is substance, essence itself,” an “acknowledgement” of the existence of the other.

Of course, the perfection of Bürgerlichkeit or civility requires certain social conditions—and multiculturalism greatly jeopardizes it, as it can make not only politics but also social life a battleground for cultural clashes. We should also remember that the notion of the middle classes makes it evident, Bürgerlichkeit comes from a hierarchically structured society. One does not wish that state of affairs back.

I propose, therefore, a notion of Bürgerlichkeit which is not based on class distinctions. Although it is close to Bildungsbürgerlichkeit, it is more than that. It is a vision of a genuinely political culture, which can be practiced even with different cultural backgrounds. It is not more than a certain attitude toward others, a certain form of interpersonal relationship. It is a behaviour defined by good manners or moeurs. A sort of sociability which allows individuals not only to tolerate the other, but even to feel sympathy towards the other, and what is more, even though they are different, and to collaborate with the other, if so it happens. All you need to do is practice it to feel like it’s yours. In that sense, it’s Hume’s l’Art de Vivre, the art of conversation.

The Philosopher and the Poet

Beyond these early modern thinkers, two other writers—a philosopher and a novelist—can help us understand what civility might look like today. The first, Hans-Georg Gadamer, writes in his opus magnum about a certain sense of tact, which he finds crucial. While in one sense the term means tempo or beat in music, Gadamer interprets this term as a rather special moral attitude: it “is not simply identical with this phenomenon of manners and customs, but they do share something essential. For the tact which functions in the human sciences is not simply a feeling and unconscious, but is at the same time a mode of knowing and a mode of being.” In other words, according to Gadamer’s understanding, civility depends on a special sort of social skill, which is itself rooted in a mode of being.

The Hungarian poet and prose writer, Dezső Kosztolányi, also wrote of something like this tact. In an early chapter of the first adventure story of his alter ego, Kornél Esti, he describes the experience of his young hero, spending a night on the train to the sea, in a compartment with a mentally disabled girl and her beautiful and suffering mother. It is at the end of that awkward and disquieting story that Kosztolányi shares with the reader the “philosophy of life” that Kornél worked out for his own personal use:

He knew that there is little that we can do for each other … and that in great affairs pitilessness is almost inevitable, but for that very reason he held the conviction that our humanity, our apostleship can only be revealed—honestly and sincerely—in little things, that attentiveness, tact, and mutual consideration based on forgiveness are the greatest things on this earth.

Kosztolányi’s hero claims that even if we can’t be good, we should be polite, where politeness “is substance, essence itself”, an “acknowledgement” of the existence of the other. His politeness is, in fact, identical with what is meant here by civility. It seems that sometimes writers can reach a philosophical truth better than professional philosophers, even if they do not grasp it fully, but only let us see it.