Discussions about global warming are almost always rooted in the idea that we should never have strayed from the pre-industrial climate. But there is no evidence that this climate was optimal. Taking it as the norm thus distorts our understanding of what we must do in the face of climate change.

Discussions about climate change, whether scientific or political, almost always take the climate as it was around 1850, at the beginning of the industrial era, as their reference point. This period is implicitly presented as a period of stable, ‘normal’ climate and, although not explicitly stated, preferable to the climate we know today. Any deviation from this period is thus interpreted as a deterioration.

However, the choice of this reference point is problematic. There is no guarantee that the climate of the 1850s was particularly favourable to humanity. Above all, this starting point tends to cast industrial development and the use of fossil fuels as inherently wrong, even though they have enabled major advances in health, comfort and risk management, particularly in relation to climate.

This choice also leads us to think of the fight against global warming in terms of sacrifice rather than innovation and improvement. So, perhaps it is time to stop referring to the pre-industrial climate, especially when framing the +1.5°C or +2°C thresholds as deviations from that norm.

A problematic point of reference

From the outset, the IPCC, which is the leading authority on climate policy, has used the climate of the pre-industrial era as a point of comparison, effectively establishing this period as the implicit norm. Its mandate, centred on analysing the impacts and risks of global warming, has even led to an emphasis on its negative effects, relegating positive or ambivalent ones to the background. Implicitly, it is therefore assumed that the climate before the industrial era was preferable.

This choice of pre-industrial climate certainly seems empirically justified, but it overlooks the fact that it influences the interpretation of the effects of global warming. Taking agriculture as an example, it is not surprising that a changing climate initially causes disruption. However, this does not mean that it is impossible, in the longer term, to adapt to a new climate regime and take advantage of it to increase agricultural productivity, especially since positive effects are already being observed in some high-latitude regions.

This same methodological bias appears in the famous concept of ‘planetary boundaries’, developed in 2009 by Johan Rockström and his colleagues. These researchers identified several biophysical variables (climate change, biodiversity, nitrogen and phosphorus cycles, etc.) for which they set thresholds that must not be exceeded, lest we enter conditions that are dangerous for humanity. However, to determine these thresholds, the authors took as their baseline the state of the Earth system during the Holocene, a period that began with the advent of agriculture around 10,000 years ago and ended with the start of the industrial revolution.

However, there is no evidence that, with some effort to adapt, human societies could not thrive even more under other climatic conditions. Yet this question has not even been raised by researchers. Here again, the reference to the pre-industrial past is seen as a model to be preserved, as if any change were inherently a negative alteration of a supposed original equilibrium.

Beyond these scholarly approaches, environmentalist discourse also describes global warming as an alteration of the natural order, caused by the supposed technological or consumerist hubris of industrial societies. Since we cannot turn back the clock, preserving nature in its current state comes to be seen as a moral imperative. One example is the French activist Camille Étienne, who justifies her political commitment by her desire to preserve glaciers indefinitely: ‘Glaciers are my backbone. They have pushed me to act, by any means necessary. These giants of ice must never perish’ (Pour un soulèvement écologique, Seuil, 2023).

However, this motivation is based on a static view of nature which, among other things, pays little attention to human suffering in colder climates. And this idealisation of past climates hinders our ability to envision how deliberate climate transformation could enhance human well-being.

The benefits of global warming

Using the pre-industrial climate as a model is particularly problematic given that, in many respects, it could be harsh for many human populations. For example, the Little Ice Age, which lasted from the 14th to the 19th century in Europe, brought long, harsh winters. Rivers regularly froze over in winter and crop failures were frequent due to cold springs or rainy summers. Indeed, the recurring famines in France in the 17th and 18th centuries were largely linked to extreme weather events, even if social and political factors contributed to worsening their effects.

In this context, global warming has brought tangible benefits to human well-being in several regions of the world. In Europe, winters have become shorter and less severe, reducing winter mortality, particularly among the elderly. We must not forget that, historically, cold spells have been more deadly than heat waves. Moreover, growing seasons have lengthened, encouraging crop diversification, particularly in northern regions. Of course, these effects are not uniform and vary from region to region, but they show that global warming is not inherently negative.

Some will argue that it contributes to an increase in extreme weather events such as heat waves, storms, floods and droughts. While some of these trends have indeed been observed, their alarmist interpretation should be tempered, as it does not consider the growing ability of human societies to adapt. Despite the increase in the world’s population, the number of deaths caused by these events has fallen sharply during the 20th century.

This evolution can be explained by technical and organisational advances: warning systems, more resilient infrastructures, emergency medicine, and coordination of relief efforts. However, these advances would not have been possible without the economic boom enabled by the widespread use of fossil fuels. While fossil fuels cause global warming, they also have the great merit of enabling human societies to reduce their vulnerability to climate hazards.

Aiming for mastery

It goes without saying that this is not an argument in favour of continued global warming. Rising temperatures, rising sea levels, destabilised rainfall patterns and ocean acidification are all phenomena which, beyond a certain threshold, pose real risks to human populations. This is why it is important to implement strategies to reduce CO2 emissions, while ensuring that the measures taken do not cause more harm than the climatic phenomena they are intended to prevent.

But we should not regret the climate of the past or demonise the historical processes – industrialisation, growth, the use of fossil fuels – that have led us to the current situation. It would even be counterproductive to do so, because it is precisely these processes that have enabled human societies to become wealthier, enjoy better living standards and protect themselves from the harshness of the climate. Rather than viewing them as an original sin, it is therefore more productive to see them as historical gains we must now learn to master responsibly.

Ultimately, it is time to change our perspective on the climate. Rather than viewing every change caused by human activity as degradation, we should see it as a manifestation of our ability to modify it. Thanks to fossil fuels, our knowledge and the techniques we have accumulated over the last two centuries, we have become capable of influencing the major balances of the Earth’s system and then understanding the mechanisms of this action. We must now mobilise this power and knowledge not to restore the planet in a nostalgic gesture, but to reshape it with the goal of enhancing human well-being.

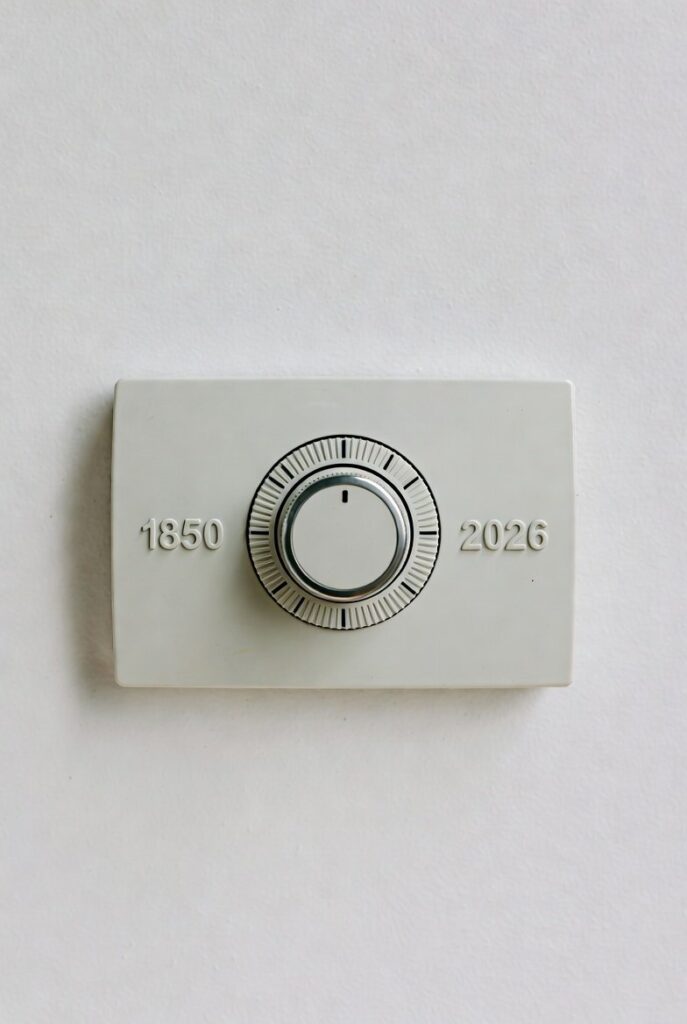

Just like a thermostat in a house, we must aim to actively regulate the Earth’s climate by greening certain arid areas, making new farmland available in high latitudes, increasing agricultural productivity through genetic engineering, promoting reforestation where it is useful, learning to control geoengineering processes, etc. The real challenge, therefore, is not to try to return to a past climate, but to develop the conditions for an optimal climate.