Caracas did not simply fracture; it exposed a subterranean axis that for years connected Havana, Tehran, Moscow, and Caracas into a single anti-Western operating system.

Under Chavismo, Venezuela was never an isolated petro-dictatorship. It was a node—trained, advised, and internally structured by Cuban intelligence, ideologically aligned with Iran, militarily courted by Russia, and operationally permissive to terrorist finance and logistics.

For Israel, this matters not rhetorically but structurally. What collapses in Venezuela today reverberates directly across the Middle East tomorrow.

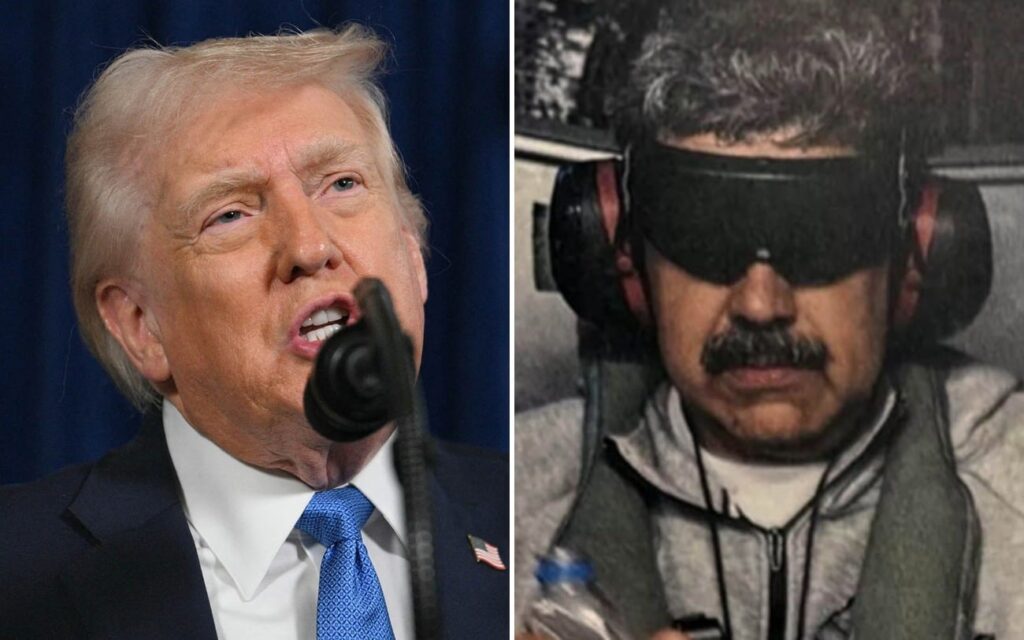

Venezuelan dictator and drug-trafficking leader Nicolás Maduro did not emerge from nowhere. He was trained by Cuban intelligence services, where Havana’s security doctrine—rooted in population control (as in East Germany, where 5 million people out of 12 million worked for the intelligence services), counterintelligence penetration, and regime survival—was exported wholesale into Venezuela’s state architecture.

In fact, Cuba functioned not as a nostalgic relic of Cold War socialism, but as the regime’s brain: embedding advisers in Venezuela’s military, intelligence, and internal security organs. This “Cubanization” of the Venezuelan state is well documented in academic and intelligence literature, and it explains why chavismo survived sanctions, protests, and economic collapse long after comparable regimes would have imploded.

But Cuba alone was not enough. The regime required external muscle and ideological depth, and that is where Iran entered decisively.

Indisputably, Venezuela became Tehran’s most reliable strategic partner in the Western Hemisphere, enabling intelligence cooperation, sanctions evasion, and proxy facilitation. This was not symbolic solidarity. It was operational alignment.

Simultaneously, Hezbollah-linked networks exploited Venezuela’s permissive financial environment, document fraud, and port infrastructure, while Iranian state entities used Caracas as a sanctions-bypass laboratory.

Hence, for Israel, this is not a Latin American curiosity—it is a forward extension of Iran’s regional strategy.

Due to this, Hezbollah and Hamas do not require embassies to operate; they require permissive ecosystems. Venezuela provided exactly that.

Through illicit finance, narcotics routes, forged documentation, and protected transit hubs—including Isla Margarita—terrorist-linked actors gained freedom of movement and funding streams far from the kinetic pressure of the Middle East.

Meanwhile, the infamous “tri-border” region in South America served as a financial hinterland, while Venezuela served as the shield. This is how modern hybrid threats survive: by geographic dispersion under political cover.

Hence, this is where Israel’s interests align directly with a Venezuelan transition. Removing chavismo is not merely regime change; it is the collapse of an Iranian auxiliary platform in the Americas. It constrains Hezbollah’s global financing networks, limits Iranian intelligence reach, and deprives Tehran of strategic depth beyond the Middle East.

Irrefutably, every state that exists within Iran’s orbit tightens the vice around its proxies elsewhere.

The Middle Eastern parallel is instructive.

Indubitably, Israel understands better than any state that ideology is secondary to infrastructure. Hamas survived not because of slogans, but because of tunnels, cash pipelines, and external sponsors. Hezbollah evolved into a hybrid army not because of rhetoric, but because Iran provided logistics, training, and state-adjacent protection. Venezuela played a comparable role—at a different scale and geography—for the same networked ecosystem. Thence, when Israel degrades those external enablers, pressure compounds inside the Middle East itself.

Nonetheless, the regional lesson long predates chavismo. Egypt, which once fought Israel repeatedly in the Sinai Peninsula, did not cease to be a threat because of ideological repentance, but because of strategic realignment, institutional restructuring, and U.S.-anchored security and economic incentives that fundamentally altered its cost–benefit calculus.

The same logic applies beyond direct belligerents. Cuba, who still exporting leftist terrorism in Venezuela today, while never fighting Israel in the Sinai itself, was embedded in the same conflict ecosystem: it deployed expeditionary forces to Syria during the 1973 war and later stationed troops and air-defense units in Egypt, exporting Soviet-aligned military, intelligence, and command doctrine across the Arab front.

In both cases, hostility diminished not through sentiment, but through structural shifts in alignment, incentives, and external patronage.

Thereby, the lesson is structural, not rhetorical. States alter external behavior when their strategic systems change, not when slogans do.

Ergo, Venezuela now sits at precisely such an inflection point. A legitimate post-Maduro government—potentially led by figures such as María Corina Machado—would represent not merely democratic renewal, but a decisive geopolitical realignment away from the Iran–Cuba–Russia axis.

Thereupon, Israel’s role should be unapologetically strategic. Reestablishing relations with a legitimate Venezuelan government is not about optics; it is about denying Iran geography.

Certainly, Jerusalem can offer what matters in post-authoritarian recovery: counter–terror finance architecture, port and border security systems, cyber defense for critical infrastructure, agricultural and water technologies that stabilize populations, and intelligence cooperation against the convergence of transnational crime and terrorism. These are not soft-power gestures; they are sovereignty tools.

For Latin America, this matters because imported Middle Eastern conflicts metastasize locally.

For the State of Israel, it matters because every permissive jurisdiction abroad becomes an operational headache at home. The erosion of Hezbollah’s financial lungs in the Americas weakens its operational capacity in Lebanon. The contraction of Iran’s reach abroad limits its bargaining leverage in the Gulf and Levant.

History rarely delivers final victories—only openings that must be exploited. If Venezuela is truly exiting the “chavista–Cuba” security model and severing its alignment with Tehran, Israel should act with speed, clarity, and institutional seriousness. The Middle East is not isolated from Latin America; it is mirrored there. And when one mirror cracks, the reflection distorts everywhere.

Unapologetically, freedom for Venezuela—may its rightful democratic leaders, including María Corina Machado and the legitimate opposition, reclaim the nation; may the eight million Venezuelans driven into exile finally return home; and may justice be exacted for every political prisoner, every tortured soul, and every life crushed by the regime.

Jose Lev Alvarez is an American–Israeli scholar.

Lev holds a B.S. in Neuroscience with a Minor in Israel Studies from The American University (Washington, D.C.), completed a bioethics course at Harvard University, and earned a Medical Degree.

On the other hand, he also holds three master’s degrees: 1) International Geostrategy and Jihadist Terrorism (INISEG, Madrid), 2) Applied Economics (UNED, Madrid), and 3) Security and Intelligence Studies (Bellevue University, Nebraska).

Currently pursuing a Ph.D. in Intelligence Studies and Global Security at Capitol Technology University in Maryland, his research focuses on Israel’s ‘Doctrine of the Periphery’ and the Abraham Accords’ impact on regional stability.

A former sergeant in the IDF Special Forces “Ghost” Unit and a U.S. veteran, Jose integrates academic rigor, field experience, and intelligence-driven analysis in his work.

Fluent in several languages, he has authored over 250 publications, is a member of the Association for Israel Studies, and collaborates as a geopolitical analyst for Latin American radio and television, bridging scholarship and real-world strategic insight.