I lead a Jewish street art movement that took shape in the months following October 7, 2023. Together with a partner and a small team, I printed and distributed more than 400,000 Kidnapped stickers after the hostage poster movement began to fade, extending the campaign by six months in cities where Jewish pain was being actively erased. When posters were torn down faster than they could be replaced, stickers proved harder to eliminate entirely. Smaller, cheaper to produce, and easier to avoid unpleasant or even dangerous encounters with, they allowed Jewish presence to persist in the face of sustained antisemitic public erasure on the street.

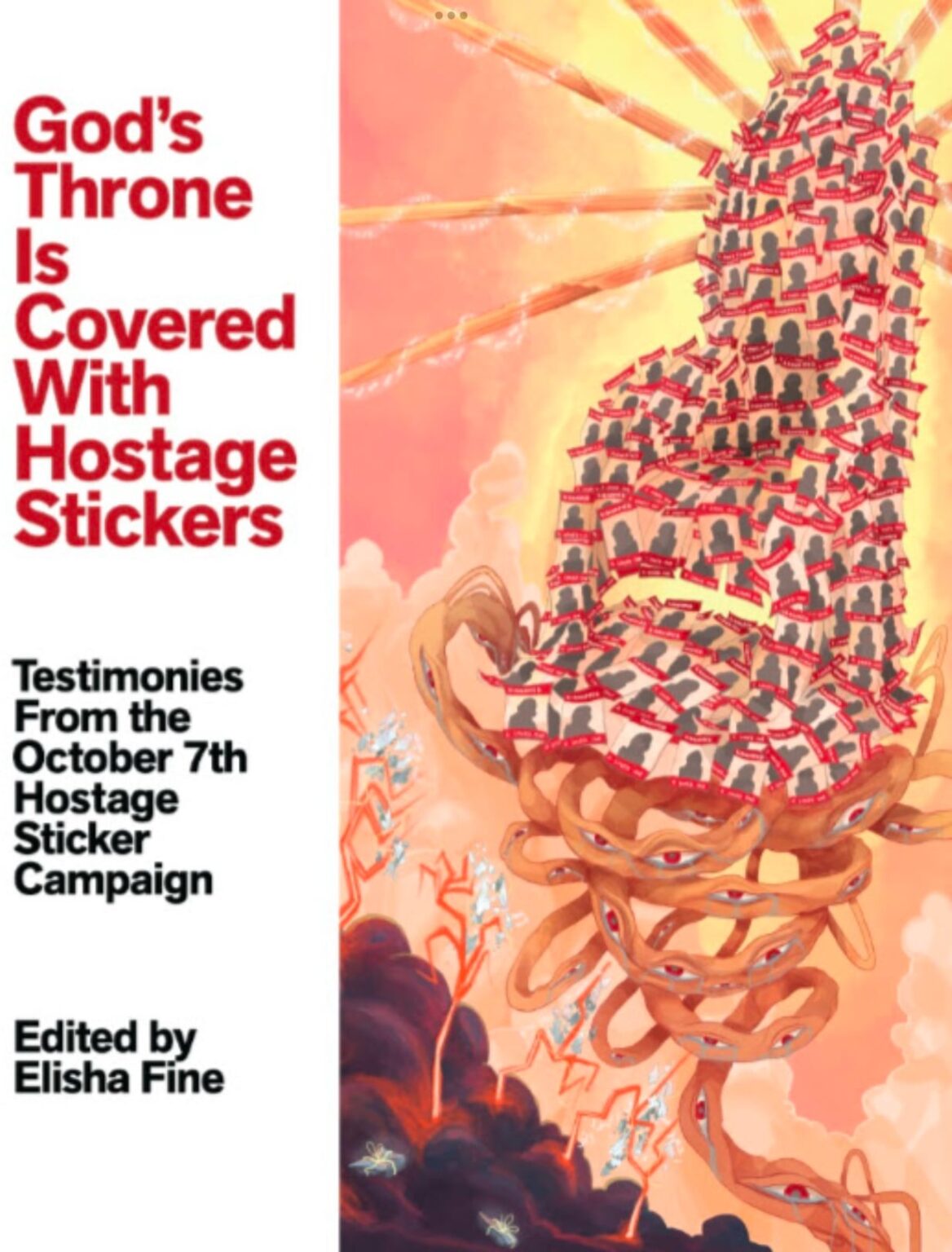

I recorded and collected the stories of these activists, many of whom proudly refer to themselves as October 8th Jews, who discovered that by changing their public environment, they could make it safer for fellow Jews in the face of new antizionist hostility. The book that came together is an oral and visual history, God’s Throne Is Covered With Hostage Stickers: Testimonies from the October 7th Sticker Campaign, grounded in a common daily experience. The book captures the inner lives of several activists across the United States and Canada and Europe. Many stories are profoundly unique to the person, their background, and personality, yet they all share the theme of keeping the hostages and the Jewish people under siege central and visible.

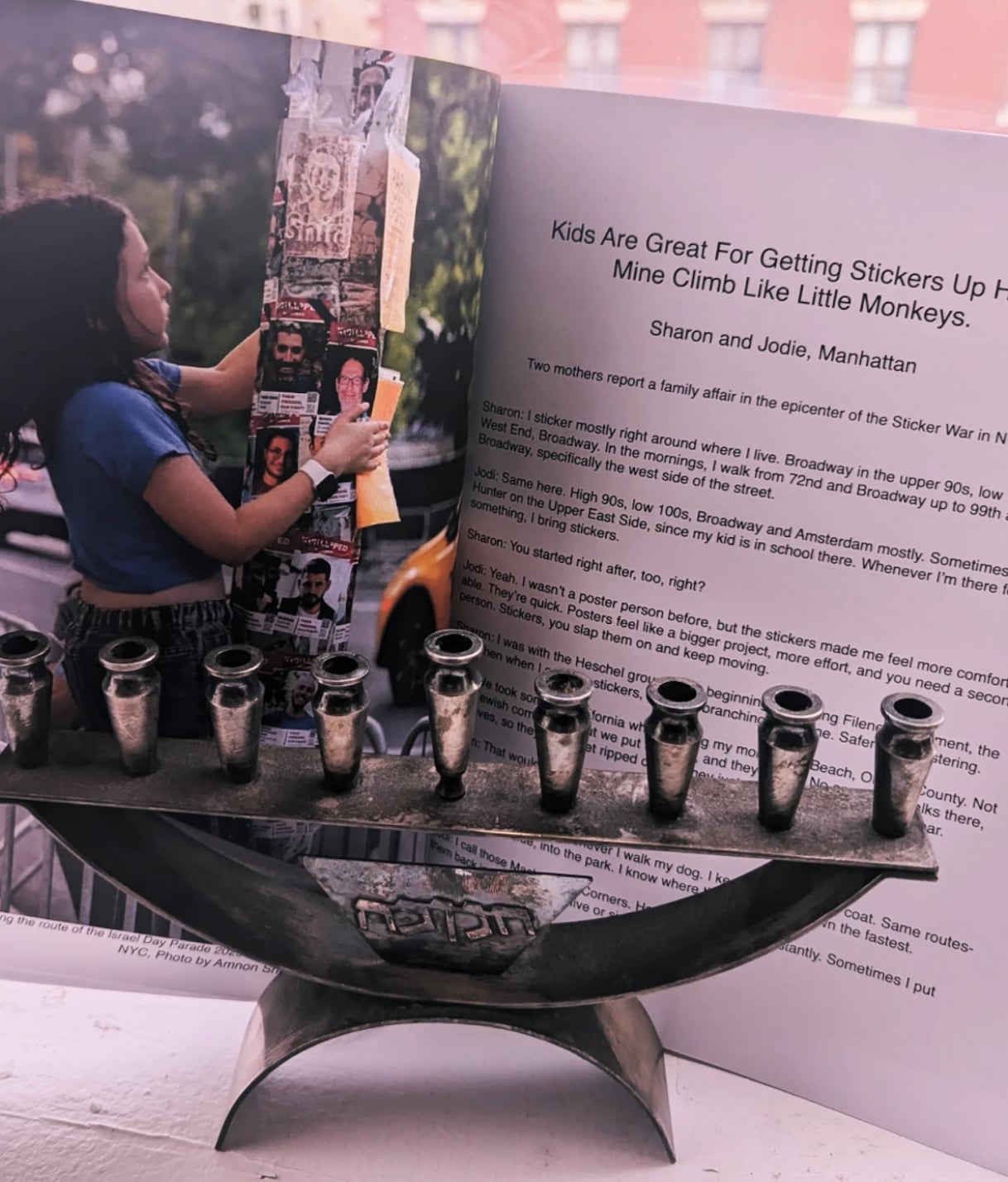

Each morning, a pole is scarred with layers and remnants of previous stickers. The previous day’s stickers are torn off by neighborhood antizionists, sometimes an anonymous antagonist, sometimes a known, persistent foe. Anyone who has been doing this for a while knows what this means.

We call this stickering. It’s a hokey name for what has become, in practice, a Jewish spiritual discipline.

Maimonides refers to tefillah as avodah she ba’lev, commonly understood as service of the heart. By tefillah, I don’t mean prayer in the liturgical sense, but rather something closer to focused, continuous action. I mean the discipline of repetition, intention, and return that gives Jewish life its durability, the kind of practice that does not promise results, only formation. What emerged in the streets after October 7th was not a replacement for synagogue prayer, but a parallel form of avodah: showing up again, in public, with care, deliberation, heart and soul — even knowing the work would be undone.

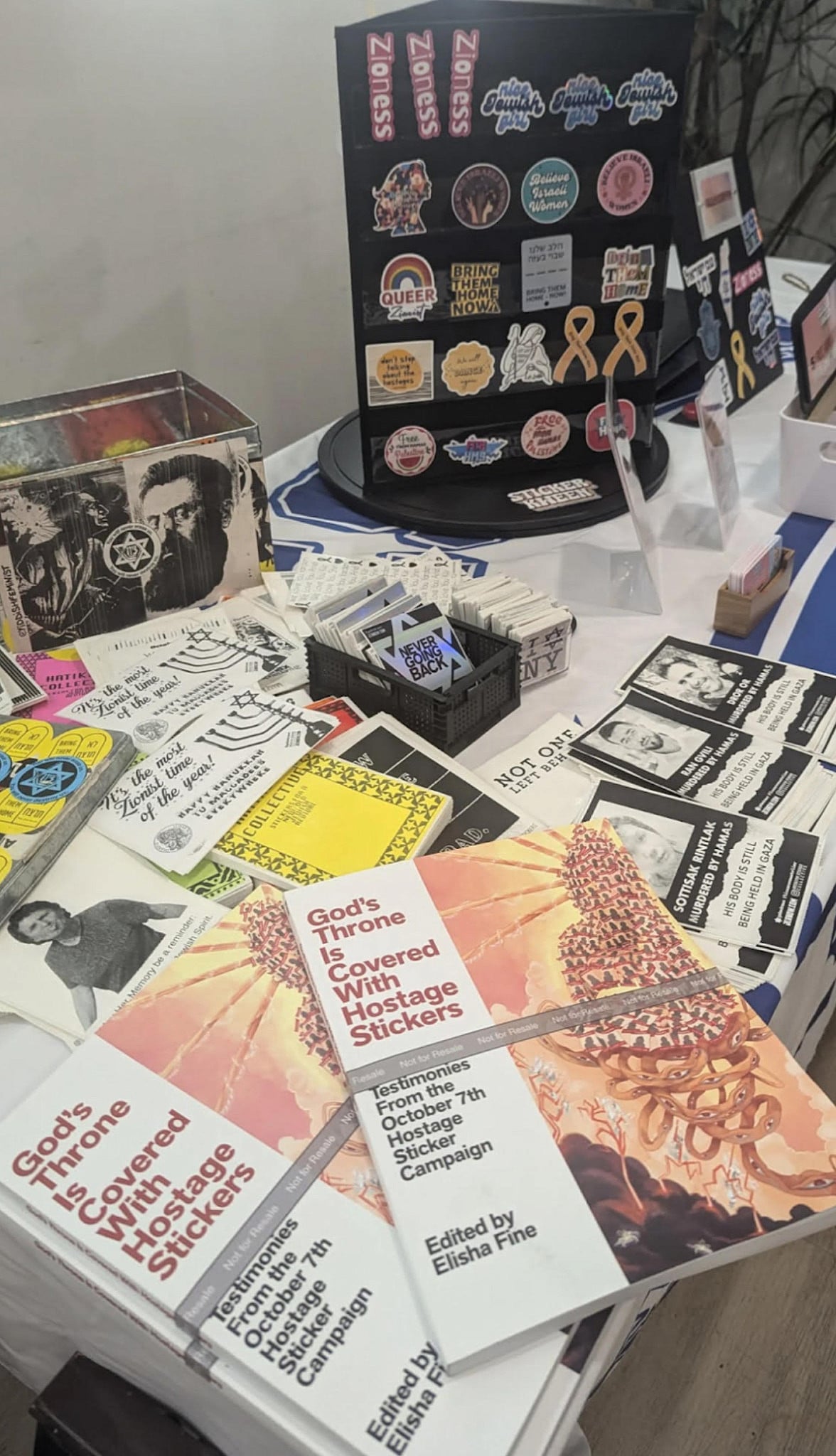

From here, needs changed, and with it, the work. I gathered a group of artists, the Hatikvah Sticker Collective, to solve a practical problem: how to make it possible for any Jewish activist to print inexpensive stickers at home and claim a small territory to tend, to “garden,” the messaging of their lived environment. Thermal printers, designed for the shipping industry, use heat to burn images onto chemically treated labels. Because the labels are manufactured for the logistics of the shipping industry, they are cheap. A basic box of white UPS-grade 4×6 thermal labels costs about forty dollars for 6,000 adhesive labels. With a thermal printer on a dining-room table, a dedicated stickerer can exert outsized influence over the mood and messaging of a neighborhood and distribute stickers to fellow activists in their community. Instead of posting something good to your stories, you could post it right to your neighborhood.

The act itself is simple, but it demands attention. You peel the backing from a four-by-six-inch pressure-sensitive label bearing the face of a hostage or a Zionist message and place it firmly in public space. You have to be deliberate. Air bubbles matter. The adhesive must be pressed flat against metal, often with the wax backing or a bowl scraper. Over time, these details become second nature. As it turns out, to my chagrin and more than slight amusement, Maimonides had a point or two about the ritual laws of prayer, repetition, and their impact on the Jewish soul.

There is also street etiquette, to be sure. In New York, stickers are placed on poles and police boxes, spaces where posting is legally unenforced and socially tolerated. Over time, the community learned not to inadvertently cover the work of other street artists. The street has its own ethics.

How one stickers — yes, it has become a verb — is a matter of temperament. Some are furtive, preferring early mornings or late nights to avoid unpleasant encounters or enjoy the quiet of a personal moment. Others make a nonviolent protest of it in the middle of the day, making eye contact and starting conversations with passersby. Some share their efforts on social media. Some keep their work local. All of it counts.

At our best, the antagonists are not the intended primary audience for this work. The audience is the mythical middle: the passersby, neighbors, and fellow Jews watching quietly, thinking perhaps about their own Jewish identity and what kind of public presence is possible.

This work is done with the full knowledge that it will not last. In many neighborhoods, stickers are torn down within a day by equally dedicated anti-Zionists, proving that the discipline is not just the placement itself, but the return, the commitment to replacing the sticker again the next day. We work on the principle of mitzvah goreret mitzvah; one sacred act leads to another. What began as a single placement became a practice sustained over time as we worked tirelessly to remember the hostages and who we are.

The persistence of this work makes us capable of public presence outside the synagogues and institutions, learning how to endure in the face of sustained antisemitic public erasure on the street, masquerading as mere antizionism. Unlike forms of activism driven, or perhaps dictated by algorithms, this work endures precisely because it asks so little at any one moment and yet so much over time. It becomes a gateway to action, to Zionist self-formation — not as an ideology, but as an open practice that leads to Jewish communal resilience. In the October 8th movement to come, this kind of readiness will, I hope in time, create the capacity required for the next inevitable crisis in our long ideological campaign against antizionism.

Gary, a friend and veteran of the Soviet Jewry movement, described it this way in the book:

My territory is mostly between 106th Street and 96th Street, up and down West End Avenue. It’s my commute in the morning and back in the afternoon, and for a while up until it got very cold and wet stickers were always in my pocket. Every day, I would replace stickers in the morning if they were gone, and again in the afternoon if they were taken down or damaged. It was a constant process. If I had stickers, I put them up.

They’re always in my right pocket. I pulled one out, looked at the face, read their name, put them in my head. Sometimes it was a struggle to peel off the backing as every sticker is different in how it comes apart. And then I would place them on a light post. That one moment of consciousness is important. I don’t live in Israel. I didn’t experience the horrors of October 7th firsthand. I don’t know anyone personally who was taken. This is my way of making their crisis real to me. Some have called it a prayer, some a meditation. It’s my way of attaching myself, of giving meaning to the action beyond just putting up something for people to see.

I recorded the stories of people like Gary in cities across North America and Europe, Jews who, beginning on October 8th, discovered that changing their public environment was a way to make Jewish life feel possible and personal again.

What has mattered most is not that this practice began in one city or with one group, but that it has proven portable. It can be taken up by Jews across the Diaspora, wherever Jewish public presence has become fragile or contested, and practiced without permission, infrastructure, or spectacle. We’ve been here before. October 7th marked a trauma. October 8th is what follows: the slow, deliberate work of return.

God’s Throne Is Covered With Hostage Stickers: Testimonies from the October 7th Sticker Campaign documents the work and people who carried it out. It is a self-published, indie work produced by a grassroots community, with a foreword by Shai Davidai and a dedication by Tal Huber, the co-creator of the Kidnapped Poster Campaign, alongside artists Nitzan Mintz and Dede Bandaid. The book is available on Amazon.

We are taking the book on tour in the New York area and on Zoom to help spread a culture of October 8th Jewish activism. To set up a book talk, contact us at elisha.fine.godsthrone@gmail.com.