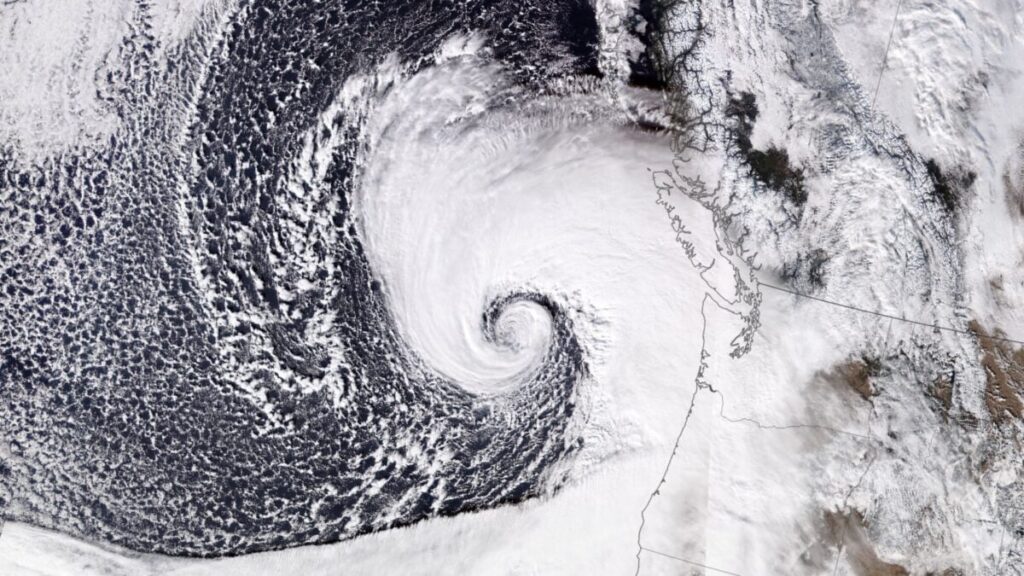

In November 2024, a powerful bomb cyclone and atmospheric river hit the Pacific Northwest, triggering severe flooding across multiple states and Canada. Like most West Coast winter storms, the system traveled along the North Pacific storm track—a major highway for mid-latitude storms that shapes the region’s weather. New research suggests the track is undergoing an unexpected change.

The study, published Wednesday in the journal Nature, found that climate change has been causing the winter North Pacific storm track to shift toward the Arctic since the late 1970s. By the end of the century, this will have significant implications for West Coast weather and water availability that current climate models don’t fully account for, according to the researchers.

“We find the climate models fail to capture the recent shift of the storm track,” lead author Rei Chemke, a climate dynamics researcher at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel, told Gizmodo in an email. “This questions the models’ ability to provide accurate projections for the region.”

Storms on the move

Previous studies have suggested that the North Pacific storm track is shifting poleward, with climate models projecting a significant shift under global warming. But the lack of a historical wind record over the ocean has prevented researchers from confirming whether the shift has occurred in recent decades and how climate change is influencing it.

“To overcome this, we establish a mathematical connection between storm tracks and sea-level pressure, which has been directly measured in recent decades,” Chemke explained. Analyzing these pressure measurements allowed the researchers to assess the position of the storm track each winter and then estimate how much its position has shifted poleward in recent decades.

The analysis confirmed that the storm track has been creeping poleward since 1979, with the center of storm activity shifting north by about 0.067 degrees of latitude per year on average. It also showed that this shift exceeds natural variability and is consistent with an externally forced change driven by human-caused warming.

Climate models fail to capture the magnitude of this recent shift. “Currently, models project a shift of [roughly] 2 degrees by the end of this century,” Chemke said. “Since the shift we observe here is not due to natural variability in the system, but rather a response to climate change, the future shift may be larger than currently predicted.”

West Coast weather will get weirder

With this critical gap in climate modeling now identified, improving how models represent storm-track dynamics will be essential for accurately projecting and preparing for future changes in storm activity, including heat and moisture fluxes along the West Coast, Chemke said.

The shift he and his colleagues measured will allow heat and moisture transported along the West Coast to reach higher latitudes and drive an increase in weather variability in those regions. This would lead to warmer conditions in the southwestern U.S., cooler and dryer conditions in the Pacific Northwest, and warmer, wetter conditions in Alaska, Chemke explained.

The West Coast is already struggling to adapt to weather extremes as climate change fuels unprecedented heatwaves, longer droughts, and more intense storms. This study highlights the complex ways that rising global temperatures are reshaping the planet’s weather systems. Understanding—and accurately modeling—these complexities will be crucial for anticipating regional impacts and adapting to a warmer world.