Inside America’s nuclear sponge and the $141 billion missile upgrade

USA TODAY’s Davis Winkie explains why the U.S. is spending $141 billion to upgrade aging nuclear missile silos.

By July 2024, the public knew the program had blown its budget. But the announcement was nonetheless staggering.

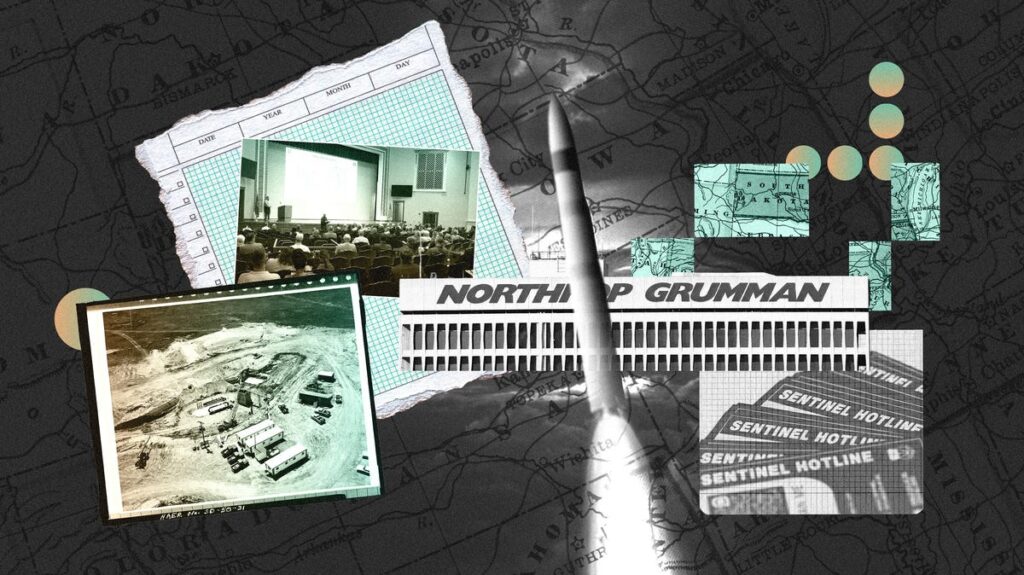

The projected price of an Air Force program to build a next-generation nuclear missile – dubbed Sentinel – had risen 81%, from $77.7 billion to nearly $141 billion. (That’s the equivalent of Americans’ combined medical debt as calculated in 2021, according to a research study.)

“There are reasons for this cost growth, but there are no excuses,” said William LaPlante, Under Secretary of Defense overseeing acquisitions at the time.

Since then, military officials and contractor Northrop Grumman have made a flurry of changes to get the Sentinel missile program back on track.

Congress wrote the current strategy into federal law, mandating that 400 land-based nuclear missiles remain on constant alert. The Sentinel missile will carry this mission into the 2070s, but it’s unclear what the final cost will be to U.S. taxpayers.

★★★

For starters, it’s been more than five decades since the U.S. pulled off a weapons program this big.

The U.S. last put new nuclear missiles into the ground in the mid-to-late 1980s, when the Air Force deployed 50 of the Northrop Corporation’s Peacekeeper missiles.

Footage shows 2022 Minuteman nuclear missile test launch

Muted footage from 2022 showed an Air Force Global Strike Command unarmed Minuteman III Intercontinental Missile launches during an operational test.

The Air Force and Northrop botched the rollout of the Peacekeeper, also known as the MX. Northrop delivered missiles without working guidance systems, leading to whistleblower claims, a government lawsuit and scathing official reports revealing delays, failures and inaccuracies in the program. The missile was retired in the early 2000s amid arms control negotiations and concerns over its cost.

Despite the snags it hit, the Peacekeeper project didn’t require new infrastructure. In fact, the U.S. has not built nuclear missile silos at scale since the 1960s, when the Army Corps of Engineers oversaw the construction of around 1,200 launch facilities; and it has not developed and mass-deployed a new intercontinental ballistic missile (or ICBM) since the Minuteman III entered service in the 1970s.

For Sentinel, the Air Force initially tried to reduce the project’s scope by directing Northrop Grumman and its subcontractors to use existing Minuteman silos for the new missile when possible.

Even without new silos, the project was to be “the largest U.S. government civil works project since the completion of the interstate highway system in the 1990s,” a pair of influential lawmakers who oversee the military – Sen. Roger Wicker, R-Mississippi, and Sen. Deb Fischer, R-Nebraska – said in a 2024 Wall Street Journal op-ed. Fischer and Wicker described Sentinel as “the most complex acquisition program the Air Force has ever undertaken.”

Former Air Force Secretary Frank Kendall, who consulted with Northrop Grumman during the early phases of the Sentinel project (and thus did not make decisions about the missile while in office from 2021 to 2025), told USA TODAY that “there was huge uncertainty about cost” of the missile program.

“The missile was a piece of that. We hadn’t built a new ICBM in about 30 years or so,” Kendall said. “But the other thing was the construction project.”

The process of renovating infrastructure and putting new missiles underground would also impact the communities near the silos. In a 2023 document detailing the possible environmental impact of the construction, the Air Force said temporary workers flooding small towns near the missile fields could “increase crime and put a significant strain on local medical, law enforcement, and firefighting resources.”

The construction project, which stretches across six Great Plains and Mountain West states, has since become even more complicated.

★★★

Contractors working on the silo project encountered a major problem when they found the service’s 450 aging Minuteman III silos rife with asbestos, lead paint, and crumbling concrete. Communication cables and other utilities also needed to be replaced.

Reusing existing launch facilities for the new missile was thus impossible, Air Force officials announced in May 2025.

Experts and former officials familiar with the project emphasized their concerns about the deteriorating condition of the existing Cold War-era silos.

Bob Peters, a career weapons of mass destruction expert who leads nuclear weapons policy work for the conservative Heritage Foundation, explained how the silos’ locations in cold winter Mountain West and Great Plains locales contributed to their sorry state.

“After 60 cold winters of freezing and thawing and freezing and thawing, that concrete is just falling apart, and (the silos) cannot be salvaged,” Peters said.

It would be cheaper – and necessary – to build new ones. The Pentagon now faces doing something it hasn’t in nearly 60 years: designing and mass producing at least 400 new ballistic missile silos. Most of the cost overruns on the project involve infrastructure issues rather than problems with the missile itself.

Kendall highlighted a key acquisition decision made when Sentinel was awarded “Milestone B” in 2020. The milestone status represents a crucial legal step for billions of dollars to begin to flow.

“You should have done your homework and have a really sound cost estimate” at that point, Kendall, the former Air Force secretary, said.

Peters suggested that the Air Force and Pentagon officials should have studied the existing infrastructure more closely before pushing the project forward. He also contends that political issues and “lawfare” from arms control and environmental groups reduced the amount of time officials had to make the call.

“There (was) a shortened contracting process, and maybe they didn’t do enough vetting on the silos … and all that stuff,” Peters said. “So they didn’t know what the costs were going to be coming down the line.”

★★★

Arms control advocates like Daryl Kimball of the Arms Control Association also say that the process wasn’t deliberate enough. (He also supports eliminating land-based nuclear missiles.)

He believes the Pentagon and Congress did not meaningfully consider alternative options that could have been cheaper.

“Going back to the later Obama administration years, there was a resistance to … looking at how the (existing) Minuteman III force” could be refurbished for longer service, he said.

Kimball said that one unexplored avenue for keeping the existing setup longer would have been reducing the number of missiles on alert, freeing up the eliminated missiles to be cannibalized for replacement parts. The Air Force could add additional warheads to the remaining missiles, so they would still be able to hit the same number of targets as today’s force, he explained.

But Congress, when overseeing cost comparisons between the Minuteman and the proposed Sentinel program, accepted the Air Force’s position that it needed to retain at least 400 missiles, the current number, until 2075. Kimball described that approach as “absurd.”

As the next-generation missile project advanced during President Donald Trump’s first administration, Northrop Grumman purchased Orbital ATK, one of the two companies in the U.S. capable of producing the type of rocket motors used in U.S. nuclear missiles.

Although the Federal Trade Commission ordered the new Northrop subsidiary not to discriminate against the company’s competition, Boeing dropped out of the Sentinel competition in mid-2019 and complained that Northrop had an unfair advantage due to its ownership of Orbital ATK.

That left Northrop as the only bidder to build the missile. During the Biden administration, the FTC blocked Lockheed Martin from merging with the other major solid rocket motor company, Aerojet Rocketdyne, and reportedly considered suing to undo the Northrop-Orbital deal.

Watchdog groups such as the Federation of American Scientists and lawmakers, including Sen. Elizabeth Warren, D-Massachusetts, cited the Northrop-Orbital merger’s potential impact on the nuclear missile’s costs as a reason to kill the Lockheed-Aerojet deal and a later successful acquisition of Aerojet by another company.

But the Northrop-Orbital merger wasn’t undone, leaving the Virginia-headquartered company as the only qualified bidder.

★★★

Arms control advocates and those who favor a beefier nuclear force agree that Sentinel costs must come down – or at least stop rising. So does the Air Force and the Pentagon, which has wrested some control of the program.

The Air Force’s top officer for ICBM programs, Brig. Gen. William Rogers, told reporters that he sees the new $141 billion cost estimate as a “cap” for the program’s price tag.

The service and Northrop recently agreed to a new framework for the acquisition program. The Air Force has started work on support facilities for the project at F.E. Warren Air Force Base in Wyoming and opened offices designed to liaise with local communities throughout the process.

The Air Force won’t be running the program much longer; Sentinel and other “critical major weapons systems” will instead be overseen by a general who reports directly to the Pentagon’s number two official.

Military officials anticipate the project will reach the silo engineering phase in mid-2027. The replacement missiles and silos likely won’t be complete until the 2050s. During that time, the U.S. will continue to rely on its venerable Minuteman III force.

Kyle Balzer, a historian of nuclear strategy who does nuclear weapons policy work at the conservative American Enterprise Institute, wants to see at least 400 Sentinels built and placed in silos designed to resist a nuclear strike. But he and other experts, such as Peters of the Heritage Foundation, see a path to increasing that number efficiently: road-mobile launchers.

The two experts recently co-authored an article (alongside Rebeccah Heinrichs of the Hudson Institute think tank) in which they argued the U.S. should consider basing some of its next-generation Sentinel missiles on trucks rather than in underground silos for part of the planned missile fleet. Russia has road-mobile ICBMs.

But matching Moscow would require approval from Congress.

Peters argued that missile-laden trucks driving around remote areas on roads built for these patrols could further magnify the sponge effect while making them harder to kill: an adversary would have to destroy the entire missile-driving circuit to have a chance of destroying them, and there would be a chance for the U.S. missile crews in the trucks could receive warning early enough to go off-road and survive the attack.

“I put my faith in empowered 30-year-old Americans to figure out, when s— hits the fan, how they’re going to ensure that (they and the missiles) survive,” Peters said.

Kimball of the Arms Control Association exhorted Americans to take a harder look at the Sentinel program in the coming years.

“Whether you’re in Kimball, Nebraska, (which arguably has) the world’s highest concentration of ICBMs per capita, or you’re in … Washington DC, we’ve got to be asking harder questions about this program,” he said. “Otherwise, we’re going to continue to spend too much and risk too much just by going forward.”

★★★

Davis Winkie’s role covering nuclear threats and national security at USA TODAY is supported by a partnership with Outrider Foundation and Journalism Funding Partners. Funders do not provide editorial input.