Lowering the voting age to 16 across the UK is a welcome policy intervention to the declining participation of young people in elections. But that alone isn’t enough to engage the youth voice, argues James Sloam. Besides participating in elections, the Government needs to engage with young people in between elections and show that it listens to their concerns.

Academics and policy-makers are concerned by declining youth participation in democracy – marked by low youth turnout in elections and membership of political parties and a lack of trust in democratic institutions. In 2025, the UK Government announced legislation to lower the voting age to 16. While welcome, this addresses the symptoms, not the causes, of the democratic deficit. The challenge is not only to give young people the vote but to give them a reason to use it.

Revitalising democracy requires improving how young people interact with policymakers between elections. One way to achieve this is through civic mentoring: a framework for local and civic authorities that allows them to create meaningful, inclusive engagement opportunities on everyday issues, particularly for marginalised youth.

The distancing of young people from democracy politics

Young people are interested in political issues but put off by formal political processes. They tend to express themselves through issue-based forms of participation in causes that have meaning for their identities and their everyday lives. Movements like #FridaysforFuture (Climate Strikes) and #Black Lives Matter have captured their energy, offering platforms that feel more authentic and inclusive.

A key driver of democratic disillusionment among younger generations is the failure of public policy to address their concerns through successive crises.

Yet the distancing youth from formal politics is dangerous. If they don’t participate, politicians ignore them, policies skew toward older voters, and disillusionment grows—a vicious circle

Political participation is dominated by older, wealthier citizens to a greater extent than in previous generations, while young people from lower socio-economic groups or minoritized ethnic backgrounds are often left out. The young Londoners I spoke to voiced scepticism even toward movements like the Climate Strikes, describing them as “having a very white face.” For many, civic engagement is grounded in survival: housing, mental health, employment, and safety.

Reimagining political participation for and with Gen Z

While much research focuses on youth turnout and trust in politicians, little explores how young people engage with policymakers between elections. This gap weakens both academic understanding and the policy response.

My new book, Turning Youth Voice into Sustainable Public Policy: the promise of urban democracy is about how we can better understand young people’s politics as the challenges they face in their everyday lives. It is about how– through engagement with local and civic authorities– young people can address these challenges for themselves and their communities. Youth participation is conceived as grass-roots engagement with policy-makers. It differs from existing studies by focussing on policy rather politics as the answer to decaying democratic institutions.

Youth participation should be conceived of as a key ingredient of inclusive and effective (“good”) governance aligning with younger generations’ preference for issue-based forms of participation. In public policy terms, it involves what Boyte describes as “a move from citizens as simply voters, volunteers and consumers, to citizens as problem-solvers and cocreators of public goods”.

The failure of public policy and the everyday politics of young Londoners

A key driver of democratic disillusionment among younger generations is the failure of public policy to address their concerns through successive crises. Policy has become more short-term and geared to older generations: in England, consider the triple lock on pensions versus cuts of around 75 per cent to youth services in the 2010s.

My research draws on a longitudinal (2019–2024) study of the Mayor of London’s Peer Outreach Team, which employs 20–30 young Londoners (aged 16–24) to engage peers and shape city policy. Most come from marginalised groups, such as care leavers. Researching with these young Londoners guided me through the complexities of being young today: growing up after the 2008 crash, a decade of austerity, the COVID-19 pandemic, and the cost-of-living and climate crises.

Despite precarity, these young people were optimistic, community-minded and civically engaged. Deliberative focus groups at City Hall in 2019 showed how many strong ideas for sustainability and public policy can emerge in a single day.

This impression of young people from lower socio-economic groups as ready and willing to engage in local decision-making is supported by empirical evidence. For example, Hansard Society data found that almost half (46 per cent) of 18-to-24-year-olds- and over half (55 per cent) of 18-24-year-olds from lower socio-economic groups– wanted to become more involved in decision-making in their local area.

Turning youth voice into sustainable policy

Young people’s everyday experiences can inform better governance. Rather than seeing youth engagement as an afterthought, young citizens should be seen as essential co-creators of policy. Involving young people early and meaningfully in the policy process leads to more inclusive, effective and sustainable outcomes.

Engaging young people in democracy is not just about increasing voter turnout—it is about cultivating a civic journey.

Nobel laureate Elinor Ostrom famously argued that people closest to an issue often understand it best. In cities, while authorities may respond to youth crime with more policing, young people see deeper causes—poverty, lack of opportunity, broken trust. One Peer Outreach Worker asked:

“Who really robs houses for fun? How many 14-year-olds would sell drugs if their families had money?”

A policymaker in the Mayor’s Office for Policing and Crime echoed this, saying:

“To do my job well, I need to be speaking to young people—there’s a wealth of experience and ideas.”

This captures the book’s core argument: youth participation is both a maker and a marker of good governance.

The civic mentoring model

Engaging young people in democracy is not just about increasing voter turnout—it is about cultivating a civic journey. When they engage, they may also influence peers, strengthen community trust, and develop skills that enhance confidence and employability.

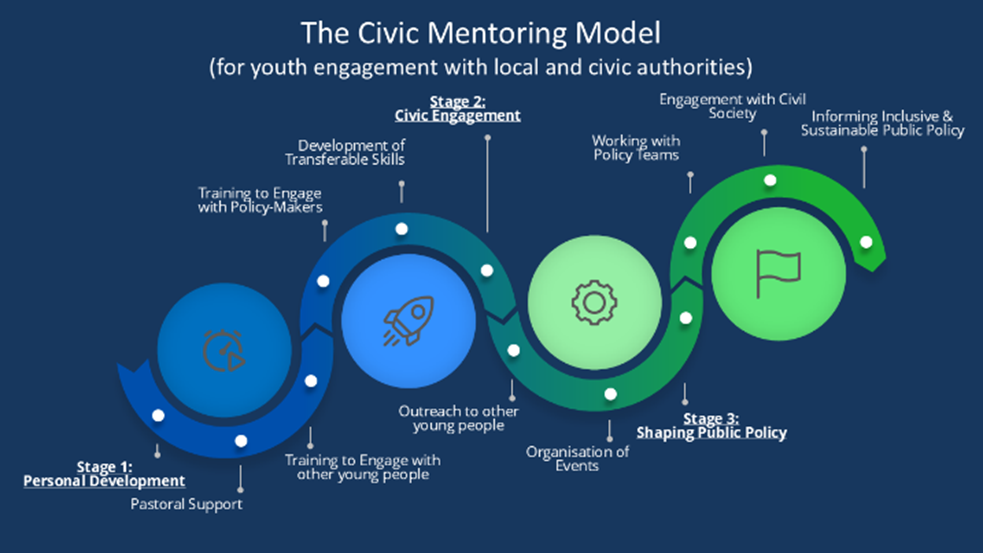

The three-stage Civic Mentoring Model, based on research with young Londoners, involves:

- Personal Development: pastoral support, to build trust and develop democratic and transferable skills such as public speaking and event organisation- essential for including marginalised youth.

- Civic Engagement: peer-to-peer projects enabling young people to lead on key issues like mental health, climate, or inequality—amplifying impact across communities.

- Shaping Public Policy: collaboration with policymakers early in decision-making processes to ensure participation is genuine, not tokenistic.

The Peer Outreach Team proved highly effective in the first two stages—building efficacy, fostering engagement, and reaching diverse peers. One Peer Outreach Worker reflected on his contribution to World Mental Health Day in City Hall:

I was really proud because the BBC came, they interviewed a couple of us… [and] my parents saw me on the news… Before I used to think that maybe my voice might not be enough… after that event I realised how much power there is behind my voice… knowing about how I can do that right now, really empowered me to get more into it and get more involved’.

In Stage 3, the team achieved notable successes– such as helping to secure council tax exemptions for care-leavers in most London boroughs. Yet barriers remained—notably policymakers’ instincts to maintain control of the policy agenda and policy-making process. As a youth voice organisation leader put it, “Councils don’t like messy decision-making– but it becomes messy if young people are involved.”

The promise of urban democracy

Research shows that youth—including those from lower socio-economic groups—are eager to influence decisions affecting their communities. Local and city authorities are key to building trust and bridging the gap between the “us” and “them” in democratic politics.

Cities like London are well suited to this model: young, diverse, and dense with civil society organisations—ideal for “empowered participation”.

Yet genuine transformation requires courage from policymakers. They must “dare more democracy” by embedding cooperative governance within institutions, listening deeply, and embracing the uncertainty that real participation brings.

The Civic Mentoring Model offers a practical pathway to amplify youth voice and strengthen local democracy—one that can be adopted in other UK cities and beyond.

Note: The introduction to the book is free to download via this link The entire book can also be purchased at the reduced rate using the code BUP11. All royalties will be donated to youth voice charities nominated by the young researchers I worked with for the study.

Enjoyed this post? Sign up to our newsletter and receive a weekly roundup of all our articles.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Image credit: Ms Jane Campbell in Shutterstock