Key Points and Summary – In the 1950s, neutral Sweden quietly explored the development of a Mach 2 strategic bomber.

-The project designation, Saab 36, was intended as a high-speed nuclear delivery aircraft.

Image of a Cold War Saab 35, a plane that would have looked similar to the A-36.

Image is of Saab Gripen fighter. Image Credit: Creative Commons.

Image is of a Saab 37 Viggen. Image Credit: Creative Commons.

-But the aircraft was never built, and has since faded into obscurity, rarely being discussed today.

-The program, despite never being pursued, raises an important question: why would a non-aligned country pursue such an extreme capability?

-The Saab 36 offers a window into general Cold War insecurities—and the constraints of ambition in the face of limited resources.

Cold War Paranoia and the Saab 36 Bomber

After World War II, as the Cold War settled on Europe, the continent rapidly militarized. Sweden remained officially neutral—but was geographically exposed, facing potential threats from the Soviet Union and Warsaw Pact air and naval forces.

As a result, Sweden pursued an indigenous defense industry offering the Nordic state maximum self-reliance.

The Saab 36 concept was borne of that desire for self-reliance—a survivable nuclear delivery platform, something to provide deterrence without dependency on the Americans, British, or French.

And back then, before advancements in SAM, AA missiles, and jet technology, speed and altitude were seen as protection against interception—leading to the Saab 36’s general premise.

Designing the Saab 36

The Saab 36 never left the drawing board; it was a conceptual design only. But the envisioned key features were a Mach 2 top speed, a high-altitude penetration profile, and long-range strike capability. The configuration was drawn up as a large delta-wing with twin engines.

The program was comparable in ambition to the US B-58 Hustler, or the Soviet Tu-22, with designs centered around nuclear weapons delivery rather than conventional bombing.

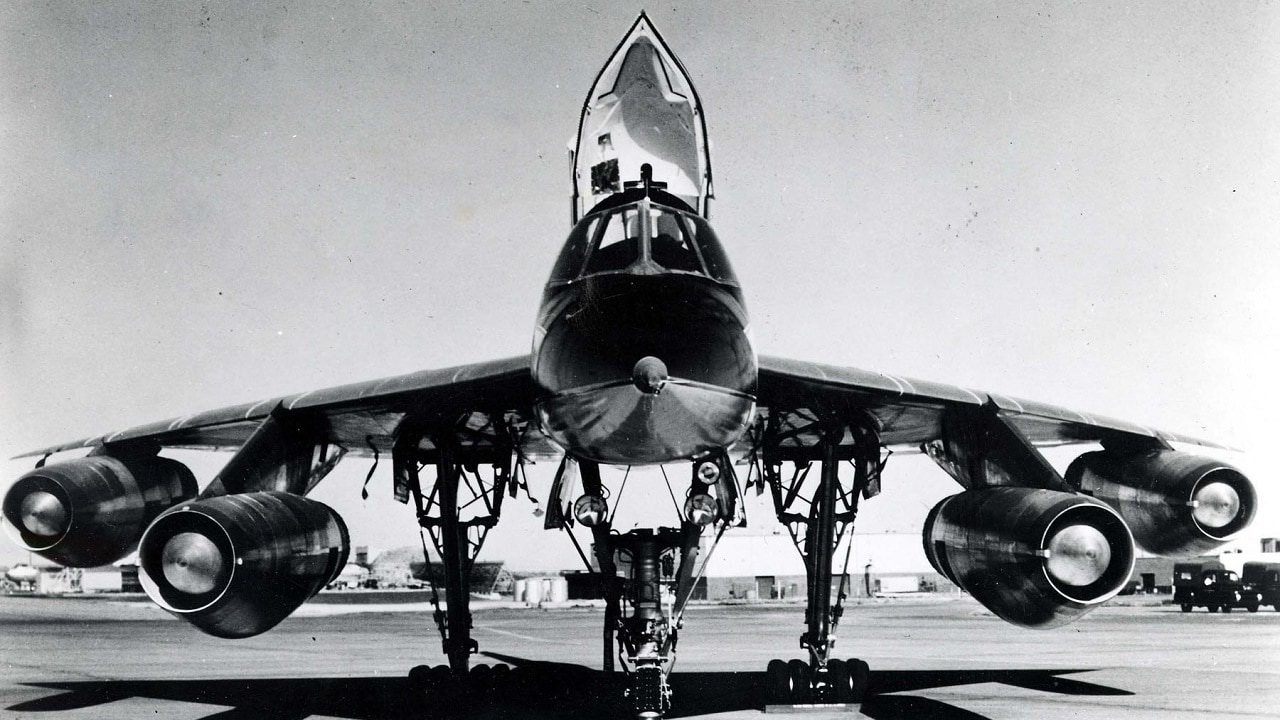

DAYTON, Ohio — Convair B-58 Hustler at the National Museum of the United States Air Force. (U.S. Air Force photo)

B-58 Hustler. Image Credit: US Air Force.

Convair B-58A Hustler front view. (U.S. Air Force photo)

The program’s technical ambition was pronounced. Sweden had strong aeronautical engineering talent—but limited industrial depth compared to the superpowers. Still, the Saab 36 pushed boundaries in supersonic aerodynamics, structural materials, and engine performance (at least on paper).

The program faced major technical challenges, particularly regarding engine thrust and reliability, thermal loads at Mach 2, and fuel consumption. Had the Saab 36 ever left the drawing board, it would have needed to solve these problems while integrating advanced avionics and an airframe robust enough to withstand the rigors of Mach 2 flight. For such a small nation as Sweden, the development risks associated with the Saab 36 were enormous, with a program budget perhaps rivaling Sweden’s entire defense budget.

Abandoning the Project

The risks were too high. The program was abandoned. Why? Because multiple pressures converged. Costs escalated.

Technical uncertainties lingered. And the strategy was erased.

The key turning point was when Sweden gradually backed away from nuclear weapons (Sweden still does not have nuclear weapons).

In addition to abandoning nuclear weapons, Sweden also shifted their doctrine from offensive deterrence to defensive air denial.

Alternatives also emerged, interceptors and SAMs, making the Saab 36 seem like a luxury pursuit. Saab refocused instead on fighter aircraft, such as the Draken, Viggen, and later the JAS 39—programs that are better aligned with Sweden’s long-term posture. Ultimately, the Saab 36 was too expensive, too provocative, and too risky—with no guarantee of program success or strategic upside.

Switching to Fighters

Rather than pursue the Saab 36, Sweden invested their industrial energy in advanced fighter-interceptors, dispersed basing, and defensive resilience. The Saab Draken was a Mach 2-capable interceptor with real, operational successes.

Later, the Saab Viggen was a multirole fighter capable of short-field operations. And the JAS 39 is arguably one of the most impressive fourth-generation fighters currently on the market. These platforms better align with Sweden’s neutrality doctrine—emphasizing defense rather than offense, choosing denial over punishment and defense over strike.

Strategic Implications

The Saab 36 demonstrates how fear can drive extreme concepts, yet how realism eventually prevails. The program also demonstrated the industrial limitations of smaller states; fiscal realities place hard limits on strategic ambition.

More specifically, bomber programs demand scale, sustainability, and political alignment. The Saab 36 ultimately failed, not because it was a bad idea, but because it wasn’t aligned with national strategy or national capabilities.

And while the Saab 36 never flew, the program did help Sweden clarify some important questions, i.e., what it was willing to pay for, how it wanted to defend its territory, and whether it wanted nuclear weapons.

The program’s cancellation worked out, leading to the development of a world-class fighter program and a more coherent defensive doctrine.

About the Author: Harrison Kass

Harrison Kass is an attorney and journalist covering national security, technology, and politics. Previously, he was a political staffer and candidate, and a US Air Force pilot selectee. He holds a JD from the University of Oregon and a master’s in global journalism and international relations from NYU.