The Migration Agency warned it was moving too fast and the parliament’s law-checking panel asked it to reconsider. But the government pushed ahead anyway, abolishing the track change law last April with retroactive effect.

Over the last few months, protests have been taking place in Sweden on a weekly basis in support of colleagues, children’s friends, and valued health workers who face deportation as a result of the abolition of the track change law last April, despite working and contributing to Swedish society for years.

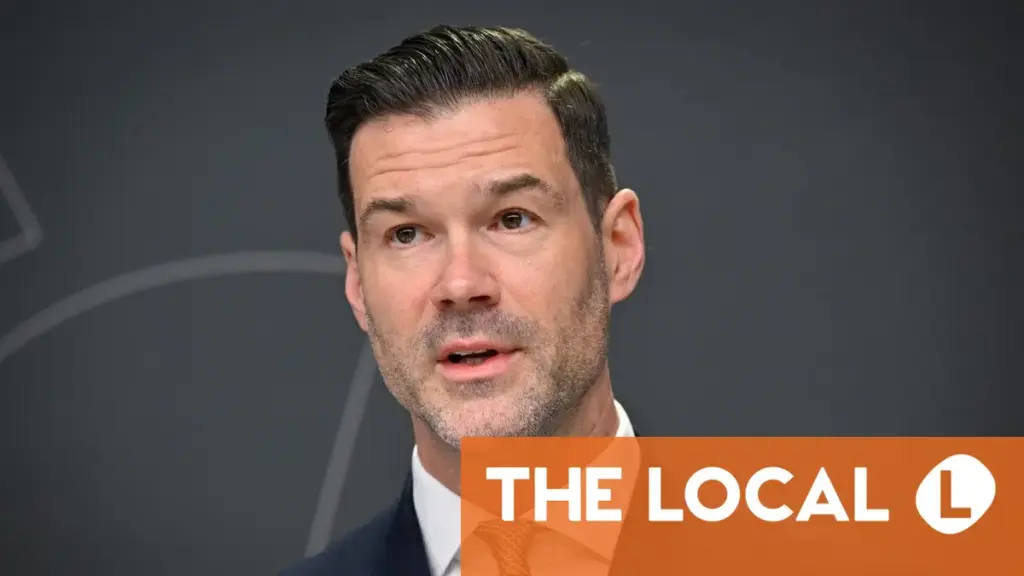

Sweden’s Migration Minister Johan Forssell on Saturday defended the decision in an article in the Aftonbladet newspaper, describing it as “a complex issue”.

“I understand that the issue brings forth strong emotions,” he wrote. “I can of course see that there are people who have worked and done everything right, and I empathise with their situation.”

These situations weren’t unexpected, however.

Advertisement

How was the law put into effect?

The abolition proposal was originally part of a broader work permit package that included the proposal to raise the minimum salary for a work permit to the Swedish median wage. This had encountered major opposition, both from the Confederation of Swedish Industry, and from the Liberal Party within the government.

So after delaying for almost a year, the government decided to break the abolition out into a separate bill, which went through an accelerated consultation in February before being approved by parliament on March 12th and coming into force on April 1st.

It was not until October 2025 that the government parties broke through their deadlock and agreed a compromise on the broader work permit package.

What issues were raised at the time?

The Council of Legislation, the parliamentary body responsible for checking the legality of proposed new laws and proposing improvements to the wording from a legal standpoint, criticised the lack of a transition period.

For many people in the middle of work permit renewals, whether they ended up staying in Sweden or got deported would come down to how fast the Migration Agency handled their case, it pointed out.

“From an equal treatment perspective, the Council on Legislation questions the appropriateness of allowing an authority’s processing times to be decisive for whether an application should be processed according to the new or older wording,” it wrote.

The need for transitional provisions, the council argued, “requires further consideration”.

The Migration Agency warned in an unusually forthright interview with The Local that the law had been rushed through “in a very short time from a legislative point of view”, and that expert agencies had not been given enough time to warn of the consequences of the bill.

Like the Council of Legislation, it said there was no way it could clear its 2,000 strong backlog of track change work permit cases before the law came into force, meaning many people would be told they had to leave the country simply because of the Migration Agency’s own processing issues.

In the parliament, only two parties ‒ the Left Party and the Green Party ‒ voted against abolishing track changes, and the two parties also made a reservation at the committee stage calling for transitional provisions.

“Transitional provisions should also be introduced from a legal certainty perspective. The legislation should be predictable and the person who has been notified of a decision should be able to base their decision on what was in force at the time the decision was notified,” they wrote.

Advertisement

What has happened since?

There have been major protests across Sweden in support of those affected by the law, including Zahra Kazemipour and Afshad Joubeh, an Iranian couple who both work as assistant nurses, Sara Ghorbani and Farhood Masoudi from Iran, who both work for the Norsjö municipality, and Fereshteh Javani, a personal assistant in Gothenburg, among others.

The decision not to have a transition period has been criticised by Douglas Thor, the leader of the ruling Moderate Party’s own youth wing, and also by Moderate Party politicians whose citizens are affected.

Stephan Serenius, a consultant doctor in the surgery department at the hospital where Kazemipour and Joubeh are employed, wrote a scathing article in Aftonbladet, and newspaper commentators write new articles calling for an amnesty almost every day.

So far, though, Forssell is unwilling to budge.

“I am aware that stricter regulations can lead to situations that can be perceived as unfair,” he wrote in his Aftonbladet article. “But the alternative would be to forgo the changes that are required for a more controlled and well-functioning migration system – the changes that the government has promised voters to implement.”