JERUSALEM — Israel’s recognition of Somaliland has thrust the breakaway territory into the international spotlight, causing an uproar in the Horn of Africa and the Middle East as a surprise new factor in regional power struggles.

For Israel, the decision reignites questions about the contentious proposal raised last year by American and Israeli officials for Somaliland to take in Palestinians displaced from Gaza. Israel also could use Somaliland as a base to more closely respond to attacks from Iran-backed Houthis rebels in Yemen, just across the Gulf of Aden.

Israel also would get a diplomatic win. Somaliland’s foreign minister told The Associated Press that it aims to join the Abraham Accords, bilateral agreements between Israel and Arab and Muslim-majority countries.

“It is a mutually beneficial friendship,” Abdirahman Dahir Adan said in an interview. In return, “Somaliland gains open cooperation with Israel in trade, investment and technology.”

But the first international recognition of Somaliland as an independent nation also could make it a target. Analysts warn that its ties with Israel could become a rallying cry for Islamic extremists, destabilizing an already volatile region in which Somaliland has prided itself as an oasis of relative calm.

Al-Qaida affiliate al-Shabab, based in Somalia and the key challenge to that country’s stability, is already making threats. The group has rarely carried out attacks in Somaliland, which broke away in 1991 as Somalia collapsed into conflict.

“Members of the movement reject Israel’s attempt to claim or use parts of our land. We will not accept this, and we will fight against it,” al-Shabab spokesperson Sheikh Ali Mohamud Rageal said in an audio message posted on one of the group’s sites.

Strategic location

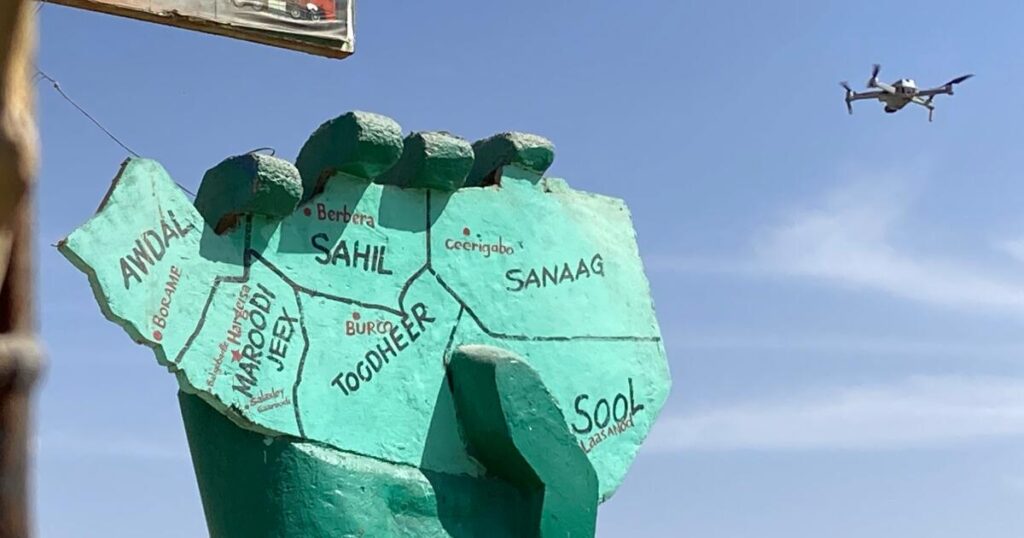

Somaliland sits along one of the world’s busiest maritime corridors. It has drawn interest from foreign investors and military powers who see it as a potential alternative to neighboring Djibouti, which is home to the premier African bases for the American and Chinese militaries, and those of several other nations.

Somaliland lies less than 100 miles from Yemen, where the Houthis have been targeting commercial and other ships in response to the Israel-Hamas war. The attacks have upended shipping in the Red Sea, through which about $1 trillion of goods pass annually. The Houthis also fired scores of missiles and drones at Israel during the war in Gaza, triggering long-range strikes by Israel’s air force.

“If you are trying to watch, deter or disrupt Houthi maritime activity, a small footprint (in Somaliland) can provide disproportionate utility,” said Andreas Krieg, a military analyst at King’s College London.

Shortly after Israel’s recognition, the Houthis threatened Somaliland.

‘No limits’ to cooperation

Israeli Foreign Minister Gideon Saar visited Somaliland last week, and Somaliland’s president is expected to visit Israel soon.

“This is a natural connection between democratic countries — both in challenging regions,” Saar said in defending Israel’s recognition.

Israel and Somaliland have said their new ties would include defense cooperation, but officials declined to elaborate. Somaliland’s foreign minister said that details would follow his president’s visit to Israel.

“There are no limits as to what areas we can work with,” Adan said.

He expressed hope that Israel’s recognition would bestow new legitimacy on Somaliland and prompt others to recognize its sovereignty, even as Somalia has angrily rejected it.

“Before Israel’s recognition, we were worried so much that other powers like Turkey and China would squeeze us,” Adan said, mentioning two of Somalia’s top benefactors. “I’m very hopeful that in the near future there will be many other countries that will follow Israel.”

But the foreign minister insisted there has been no discussion with Israel about taking in Palestinians from Gaza. U.S. and Israeli officials told the AP last year that Israel had approached Somaliland about the proposal.

Warnings of violence

Israeli recognition of Somaliland has pushed the region into uncharted waters, said Mahad Wasuge, director of Public Agenda, a Somali think tank.

“It could increase violence or bring proxy wars, particularly if the Israelis want to have a presence in the port of Berbera to counter threats in the Red Sea,” he said, referring to Somaliland’s largest port.

The 57-nation Organization of Islamic Cooperation, and the African Union continental body, have condemned Israel’s recognition.

Somali President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud has said it threatens his country’s sovereignty. He said that Somalis wouldn’t accept their nation being used by a foreign power accused of harming civilians — meaning Palestinians in Gaza — and warned that the establishment of foreign military bases would further destabilize the region.

Somali territory “cannot be divided by a piece of paper written by Israel and signed by (Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin) Netanyahu,” Mohamud said in a televised address.

Adan dismissed the criticism from Mogadishu, calling Somalia a “failed state.”

Great power rivalries

Already, Israel’s recognition has rocked the balance of powers in a region where rich Gulf countries and others have a growing interest.

On Monday, Somalia annulled its security and defense agreements with the United Arab Emirates, a key regional ally of Israel that has long invested in Somaliland’s Berbera port, saying it was meant to safeguard “unity, territorial integrity, and constitutional order.”

For the UAE, the area is important for its proximity to Sudan, where it has been accused of funding and arming the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces in that country’s civil war. And last week, Saudi Arabia accused the UAE of using Somaliland as a transit point to smuggle the leader of a separatist group out of southern Yemen.

Asher Lubotzky, an analyst with Israel’s Institute for National Security Studies, said that Somaliland is one of several examples of the emerging alliance between Israel and the UAE, which have sought to align with U.S. foreign policy and shown a willingness to eschew international norms while countering extremist groups.

“We know the Israeli interest is with the Houthis, but Somaliland also has an interest in some kind of an external protection,” he said.

Others put on alert by Israel’s recognition are China and Turkey. Somali ports are a key focus of Chinese regional investment, and Beijing has long viewed Somaliland with suspicion over its ties with Taiwan. Turkey is Somalia’s largest investor and a rival to Israel.

Closer to home, landlocked Ethiopia, Africa’s second-most populous country, sees Somaliland next door as a key route to the sea. It has remained silent on Israel’s recognition — perhaps scrambling, like many other countries, to understand what might come next.

Metz and Faruk write for the Associated Press. Faruk reported from Mogadishu, Somalia. Samy Magdy in Cairo, and Josef Federman in Jerusalem, contributed to this report.