![Vietnamese migrant workers harvest radishes in a field in Yeongam County, South Jeolla, on Dec. 4, 2025. [HWANG HEE-GYU]](https://www.byteseu.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/5ec4218d-b9d1-4a18-b4f4-79019603d836.jpg)

Vietnamese migrant workers harvest radishes in a field in Yeongam County, South Jeolla, on Dec. 4, 2025. [HWANG HEE-GYU]

Kobiljon, a 42-year-old migrant worker to Korea from Uzbekistan, shared his New Year’s wish over a glass of beer on Dec. 27, 2025 — to play a song on the guitar that sounded like rain falling on his hometown.

He then raised his glass for a toast at a fried chicken joint in Samho-eup, a quiet rural neighborhood in Yeongam County, South Jeolla — a couple of thousand miles from home.

Dressed in a navy-blue work uniform, Kobiljon shared his hopes for the year ahead while sitting with a group of fellow migrant workers and two local business owners — Park Chan-su, the 79-year-old who runs a nearby studio apartment, and Park Kyung-ran, the 55-year-old who owns the chicken shop. Originally from Uzbekistan, Kobiljon has been working at HD Hyundai Samho since 2022 on an E-9 nonprofessional employment visa.

Others shared similar hopes. “I hope to get along well with the people I work with,” said Kirill, who is from Russia. Aibek, from Kazakhstan, added, “I wish for my family’s health, and to make good money.”

“These foreign workers come here all alone, work hard and send everything they earn back to their families,” Park, the studio apartment owner, remarked. “If they could live here with their families, wouldn’t that be a good thing for Korea, too?”

In Yeongam County, foreign nationals now make up more than one in five residents, or 21.1 percent — the highest proportion among all municipalities in Korea.

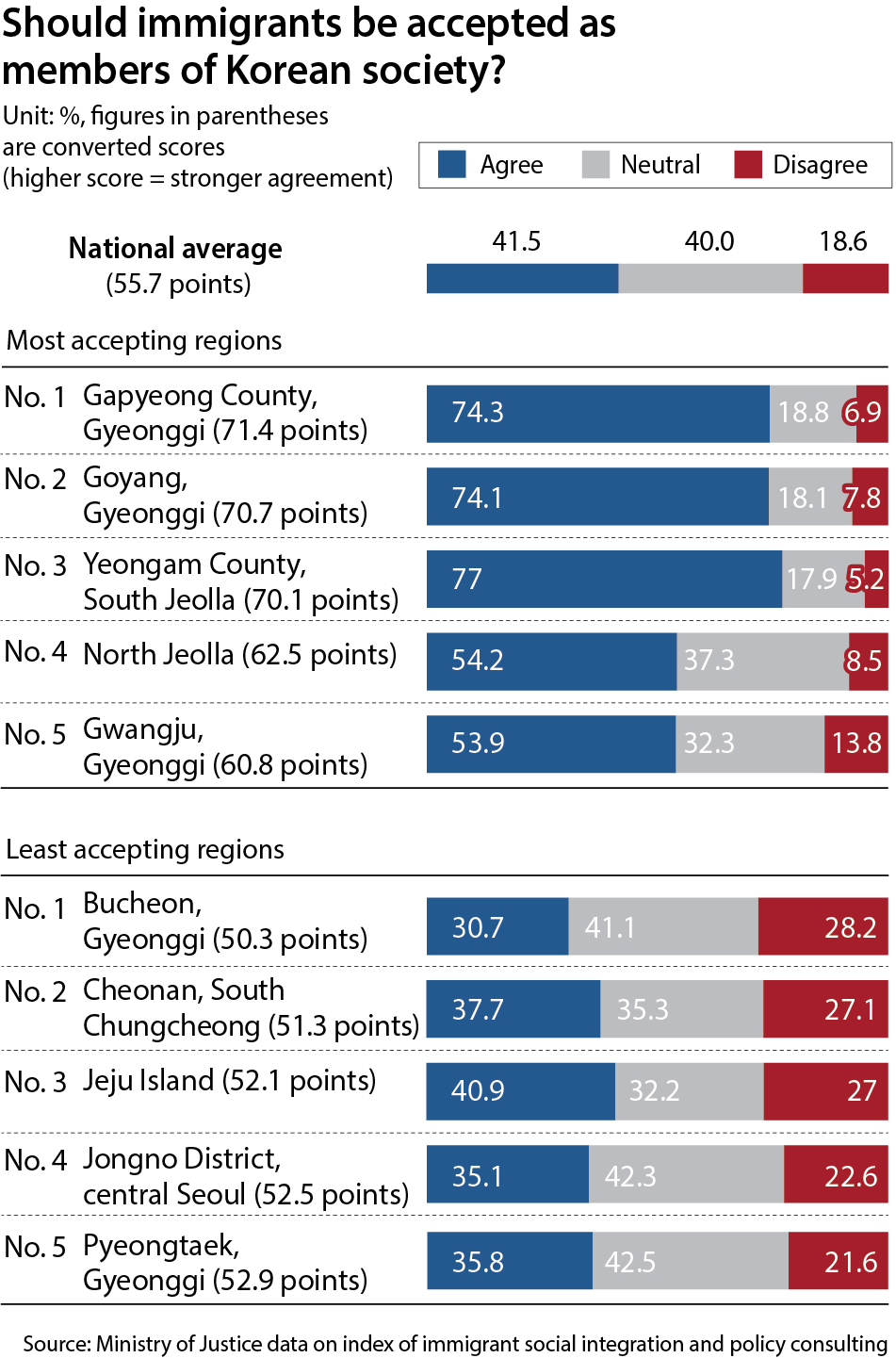

According to a report by the Ministry of Justice’s Migration Research & Training Centre obtained by the JoongAng Ilbo, Yeongam had the highest acceptance rate in the country when residents were asked whether they viewed immigrants as members of Korean society. The figure stood at 77 percent, the highest among 17 metropolitan and provincial governments and 22 municipalities with more than 10,000 registered foreign residents.

Between Aug. 19 and Sept. 20, 2024, the research center surveyed 6,000 Korean nationals and 6,000 immigrants, defined as long-term foreign residents and naturalized citizens who became Korean nationals within the last five years.

The sample was stratified by visa status, region, gender and age to reflect Korea’s immigrant population of approximately 1.85 million. The margin of error was plus or minus 1.6 percentage points at a 95-percent confidence level.

By contrast, only 40.9 percent of respondents on Jeju Island said they agreed with viewing immigrants as members of Korean society, placing the island near the bottom. Jeju also had the highest percentage of respondents, or 11.6 percent, who said they “strongly disagree” with the idea.

![A farmer in rural Jeju transports an undocumented Chinese migrant in his truck on Sept. 18, 2025. [KIM JEONG-JAE]](https://www.byteseu.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/6ba84349-681b-4d18-9295-10cc961080ad.jpg)

A farmer in rural Jeju transports an undocumented Chinese migrant in his truck on Sept. 18, 2025. [KIM JEONG-JAE]

Despite its push to minimize regulatory barriers for businesses and promote tourism through its visa-free entry policy — which allows foreign visitors to stay for up to 30 days — Jeju has also seen a surge in undocumented migrants. The island, which is estimated to have been visited by at least 2.24 million tourists last year, is also home to illegal labor dispatch offices, some reportedly run by Chinese nationals.

As of late November 2025, a total of 2.73 million foreign nationals were residing in Korea. Among them, more than 2.16 million were long-term residents staying over 90 days.

Of the 1.61 million registered foreign nationals — excluding overseas Koreans — approximately 600,000, or 37.5 percent, held employment visas. That’s why 60 of the 457 workers who died in industrial accidents through September last year — or 13.1 percent — were foreign nationals.

“Foreign nationals now account for 5.3 percent of Korea’s population, and their numbers are growing, fueled in part by the global popularity of Korean culture,” said Yoo Min-yi, a researcher at the Migration Research & Training Centre. “We’ve entered the era of immigration, and it’s time to view immigrants not just as a labor force but as people — that is, as members of society.

“Since public acceptance of immigrants varies significantly depending on whether immigration is seen as safe and orderly, there is a need to improve the visa system and broader immigration integration policies,” Yoo continued.

This article was originally written in Korean and translated by a bilingual reporter with the help of generative AI tools. It was then edited by a native English-speaking editor. All AI-assisted translations are reviewed and refined by our newsroom.

BY YUN JUNG-MIN, LEE YOUNG-KEUN, JUN YUL, KIM JEONG-JAE [[email protected]]

![Some regions of Korea more accepting of migrants than others, survey suggests Vietnamese migrant workers harvest radishes in a field in Yeongam County, South Jeolla, on Dec. 4, 2025. [HWANG HEE-GYU]](https://www.byteseu.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/5ec4218d-b9d1-4a18-b4f4-79019603d836-1024x768.jpg)