This is the 15th article in a series by The Athletic looking back at the winners of each men’s World Cup.

Previously, we’ve looked at Uruguay in 1930, Italy in 1934 and again in 1938, Uruguay in 1950, West Germany in 1954, before a Brazilian double in 1958 and 1962, an England success in 1966, another Brazil win in 1970, a second West Germany triumph in 1974, Argentina’s first win in 1978, Italy’s third in 1982, Argentina’s second in 1986, West Germany’s third in 1990, and Brazil going clear with a fourth World Cup in 1994. Now, it’s time for someone new to get involved.

Introduction

A tournament that is fondly remembered, and a triumphant side that were celebrated as deserving winners. France were — in modern times — that rare thing, a victorious host nation. Divide the 22 World Cups in half, and while five of the first 11 were won by the host, this is the only one of the last 11 tournaments to have been won by the country staging the event.

As with many World Cups, there was a wider political angle. Amid a rise in support for far-right National Front leader Jean-Marie Le Pen, who had repeatedly criticised the national side for having too many players born outside France, or from an immigrant background, France’s eventual success was seen as a victory for the side’s multiculturalism as much as its football approach.

The manager

As a general rule, French managers tend to take something of a back seat role. They’re not overly concerned with footballing philosophy, they aren’t constantly tinkering with their side, they aren’t larger-than-life characters in press conferences.

Aime Jacquet had enjoyed great success with Bordeaux in the 1980s, and subsequently worked for the national side as technical director and then assistant manager, during which time France failed to qualify for World Cup 1994. He was then appointed as manager, but was constantly criticised in the French press, largely for being too conservative. But Jacquet knew what was needed to win a tournament: a good defensive record, a harmonious atmosphere, and lots of players chipping in with goals.

Jacquet never coached another game after the 1998 World Cup final (Shaun Botterill/Allsport)

Even in victory, Jacquet was still rattled by the previous negativity towards him. “The team got better as the tournament progressed, and we showed we have some world-class players,” he said after the final. “The supporters also got more confidence in us as the games went by. But we have been unfairly criticised at times, and I’ll never forgive those critics who were so severe on us after we failed to qualify for USA 94.”

He never coached another game after the World Cup final, reverting to his position as technical director.

You might be surprised to learn…

For all the joyous scenes after the final, France was struggling to love its national team until midway through the tournament. Missing out on World Cup 1994 was still considered a national embarrassment. The side also struggled to reach Euro 96 — a Youri Djorkaeff free-kick in a qualifier against Poland probably kept Jacquet in his job — and while France reached the semi-finals of that tournament, they didn’t score a single goal in four hours of knockout football. France wanted something more beautiful.

Outside France, there were questions about precisely how much this was a football-mad country. Ligue 1 attendances averaged only 16,000. Star players were leaving after the Bosman ruling, and French tax rates meant its clubs couldn’t compete financially. The lack of competitive games in the build-up to the tournament meant there was little for fans to get excited about. Captain Didier Deschamps called for fewer shirts and ties in the stands, and more France shirts.

Nevertheless, France seemed to suddenly become obsessed midway through the tournament — the more France progressed, the more its citizens watched matches in big groups in public places, rather than at home. The scenes after the final were so memorable because they felt so unlikely going into the tournament. The Ligue 1 average attendance rose more than 20 per cent for the following season.

France’s supporters grew to love their team as it progressed through the tournament (Gabriel Bouys/AFP via Getty Images)

Tactics

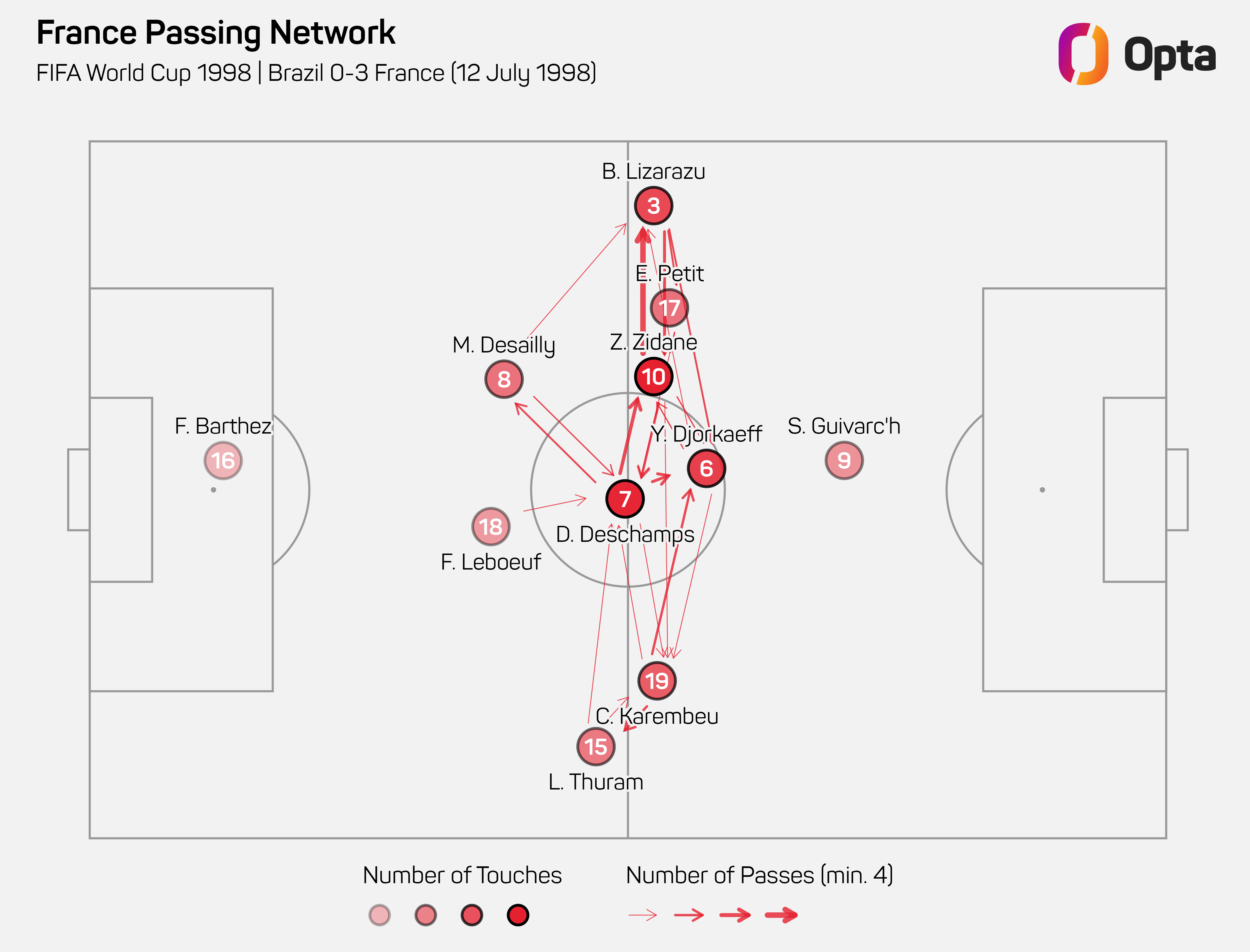

France ended the tournament with a 4-3-2-1 formation, which lacked both attacking width and speed.

Striker Stephane Guivarc’h was mocked for his inability to score a single goal at the competition. He was retrospectively praised for his ability to hold up the ball and run the channels, but he constantly slipped when through on goal, or haplessly scuffed the ball. “No team has ever won the World Cup with such ineffective forwards,” said the editorial in World Soccer magazine.

Behind, Zinedine Zidane and Djorkaeff provided some attacking spark — Djorkaeff from slightly higher up the pitch, offering more of a goal threat in open play. They had the security of three solid players behind them: the ultra-solid water carrier Deschamps, the cautious Emmanuel Petit, who offered left-footed balance, and then the workmanlike Christian Karembeu, who offered more energy to the right. The passing network for the final makes them look like 2-7-1, with the full-backs pushing on, the wider midfielders spreading, and the two No 10s coming short to get the ball.

Earlier in the competition they had offered more speed and urgency, particularly when using a young Thierry Henry from the wing, and David Trezeguet at times too. Meanwhile, Christoph Dugarry started up front and scored France’s opening goal of the competition, although was ruled out for most of the tournament with a hamstring injury. As regularly happens, the eventual World Cup winners became more cautious as the tournament developed.

🏆 David Trezeguet was the youngest member of France’s 1998 #WorldCup-winning squad, netted the golden goal that won them EURO 2000 and remains their 5th highest all-time scorer 🇫🇷

🥳 Happy birthday to an elite marksman ⚽️

@Trezegoldavid | @FrenchTeampic.twitter.com/Jj7glHQ0PT

— FIFA World Cup (@FIFAWorldCup) October 15, 2021

The defence was celebrated as the the most solid in the competition, although almost everyone ran into some problems along the way. In the 4-0 win over Saudi Arabia, goalkeeper Fabien Barthez got away with a two-footed lunge and left-back Bixente Lizarazu was also lucky not to be dismissed for a last-man foul.

In the semi-final, Lilian Thuram ended up five yards behind his fellow defenders to play Davor Suker onside for Croatia’s opener. Later on, Laurent Blanc was controversially sent off after whacking Slaven Bilic in the chest, prompting Bilic going down holding his head. That meant Frank Leboeuf coming in for the final to play alongside Marcel Desailly — and then Desailly was sent off midway through the second half for a wild challenge on Cafu which resulted in a second booking.

This meant France ended the tournament with backup Leboeuf playing alongside Petit, who had dropped back from midfield into the position he used to play with Monaco. It was all a bit more ramshackle than often portrayed. But it’s worth pointing out that France scored six goals in the knockout stage, and four — one from Blanc, two from Thuram, and another from Petit late in the final — came from those playing in defence.

Emmanuel Petit scored France’s third goal against Brazil (Stu Forster/Getty Images)

Star player

Zidane had long been cast as France’s superstar, and given he scored twice in the first half of the final to give France a 2-0 lead they never looked like relinquishing, he became the poster boy for this side — literally, as his face was projected onto the Arc de Triomphe while Parisians celebrated up and down the Champs Elysee.

Zidane’s face projected onto the Arc de Triomphe (Jack Guez/AFP via Getty Images)

But this wasn’t Zidane at his best — his outstanding tournament was Euro 2000, and he performed better at World Cup 2006 too — and in the aftermath of the tournament most journalists’ attempts to create a best XI didn’t feature his name.

Here, he was sent off in the 4-0 group stage victory over Saudi Arabia for stamping on Fuad Amin, which meant he was suspended for two matches. Such was the clamour for Zidane to be the main man — the new Michel Platini — his absence almost overshadowed France’s progress.

Upon his return, he was marked out of an uneventful goalless draw with Italy by his Juventus team-mate Gianluca Pessotto in the quarter-final, but was excellent against Croatia in the semi.

Thuram and Desailly were hailed as France’s best players throughout the tournament, but after the final, Zidane was clearly the star.

The final

The 2002 final would be about Ronaldo. The 2006 final would be about Zidane. This was about both.

The build-up to the game is perhaps more memorable than the game itself, with two separate Brazil team sheets appearing — the first with Ronaldo somehow not in the side and replaced by Edmundo, then a revised version with Ronaldo reinstated. It later emerged that Ronaldo had experienced a series of convulsions while having his afternoon nap, and had spent several hours in hospital. He arrived at the Stade de France separately from his team-mates.

He eventually played the full 90 minutes, but was clearly lacking his usual spark. Amid these pre-match worries, Brazil had barely warmed up before the game, and never really got going.

Ronaldo looks on as Zidane opens the scoring in the final (Omar Torres/AFP via Getty Images)

France dominated without playing spectacular football, and were 2-0 up at half-time thanks to Zidane’s two headers, both after beating Leonardo to reach an inswinging corner. “Scoring two with my head is unbelievable,” he said afterwards. “I’m not very good with my head. But both times the ball came over perfectly for me, and I managed to connect perfectly.”

There was little reaction from Brazil, even after Desailly’s red card on 68 minutes. 2-0 seemed a fair scoreline, but Petit added the icing on the cake after being slipped in by his Arsenal midfield colleague Patrick Vieira, to make it 3-0.

🔊 “The day of glory has arrived,” sung @FrenchTeam players & fans as La Marseillaise boomed across Paris #OnThisDay in 1998 🏟️

🤩 Zidane headers, a glorious counter-attack & a magnificent performance ensued

🇫🇷 France’s ‘Jour de gloire’ had truly arrivedpic.twitter.com/2h7VqOxBsG

— FIFA World Cup (@FIFAWorldCup) July 12, 2020

The defining moment

Probably the single most joyous moment was Thuram’s second against Croatia in the semi-final. His error meant France fell behind for the only time in the competition, which prompted France’s most intense spell of the World Cup, and he was the fitting man to turn things around. This was a right-back who had never previously scored for France — and never would do so again — but he momentarily transformed into a goalscoring machine, first grabbing the equaliser a minute after Suker’s goal and then, even more improbably, curling home with his left foot from outside the box.

“It was what I call my Miles Davis moment,” he later told The Guardian. “Footballers can be like artists when the mind and body are working as one. It is what Miles Davis does when he plays free jazz — everything pulls together into one intense moment that is beautiful. He doesn’t have to think about it; it’s pure instinct… we do not know why it happened, but it worked.”

A brace that secured France a place in the 1998 #FIFAWorldCup Final! ⚽️⚽️ pic.twitter.com/wSAiyEBJsy

— FIFA World Cup (@FIFAWorldCup) July 8, 2024

Were they definitely the best team?

Brazil were the favourites going into the final, and showed more attacking flair than the hosts — as did the Netherlands, Croatia and Argentina, in all honesty.

During this period, winning the World Cup seemed to primarily be about collecting clean sheets. France had a strong defence, they protected them with solid holding midfielders, and they ultimately conceded only two goals in seven matches, a stark contrast from Brazil.

“We conceded 10 goals in our seven games,” acknowledged Brazil captain Dunga afterwards. “You cannot expect to win the World Cup like that.” Brazil would return four years later with a better defence — and a fit Ronaldo.