Conflict over robots controlled by artificial intelligence (AI) is no longer a scenario in the distant future for Korea. It is unfolding in real time, as changes to the country's labor law give unions new leverage over how quickly and extensively companies can replace human workers with machines.

Experts say the recently enacted pro-labor “yellow envelope law” set to take effect in March may slow the transition to robot labor. The law expands workers’ rights in labor disputes and limits employers’ ability to seek damages from unions over strike-related losses, giving unions more leverage. Paradoxically, it could also hasten automation, as companies rush to install robots before union power increases and their legal risks grow.

Nowhere has that tension become more evident than at Hyundai Motor, which has become a test case for how far unions, employers and the government can go to shape the coming wave of “physical AI,” with AI robotic systems carrying out hands-on work on factory floors.

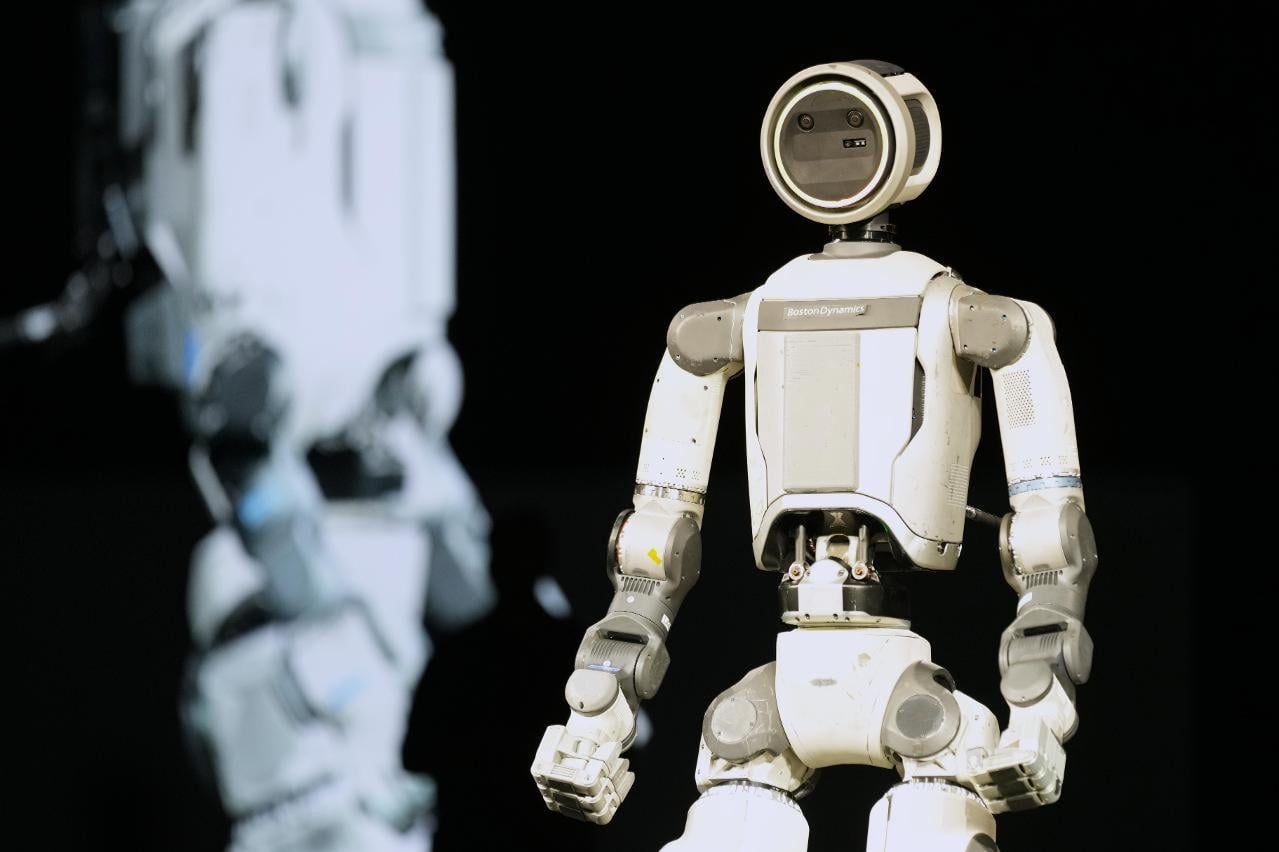

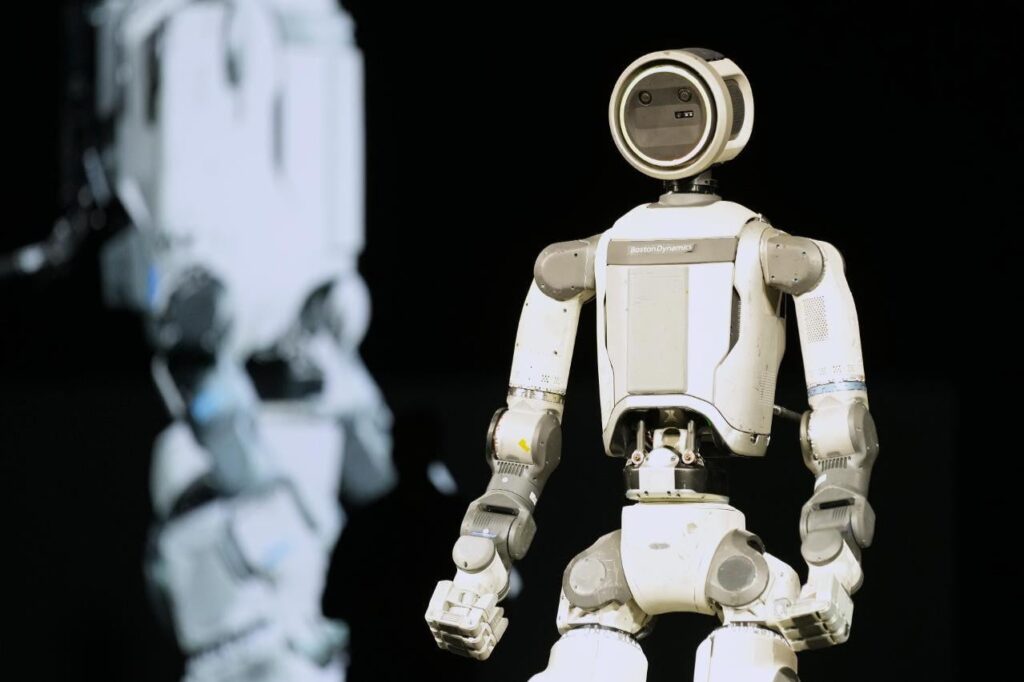

The company announced last week that it plans to mass-produce Atlas humanoid robots at a new U.S. plant by 2028, and gradually deploy them across its assembly lines. Hyundai Motor is pitching the project as the cornerstone of its physical AI future, in which AI-controlled industrial machines work alongside or in place of humans to handle risky or monotonous tasks.

Some industry analysts estimate annual maintenance costs at roughly 14 million won ($9,700) for each Atlas robot, which can operate for nearly 24 hours a day, compared with human employees who cost the company about 130 million won per year each.

Unionized workers at Hyundai Motor protested the move, saying in a statement “not a single robot” will be allowed onto the assembly floor without a labor-management agreement.

This warning is being taken seriously. Under the new law, management decisions that significantly affect working conditions are recognized as matters for collective bargaining and action. Large-scale automation projects fall squarely into that category, according to labor experts. That means unions can more easily strike or take other collective action to resist or shape robot deployment strategies.

“This is a turning point for Korea,” Ahn Jong-ki, a professor at the Korea University Institute for Research on Labor and Employment, told The Korea Times. He believes that in structural terms, the direction is already set.

“Large-scale substitution of human labor by robots and AI is unavoidable, and it is likely to proceed much faster than most people expect,” he said. “The real question is not whether this will happen, but whether labor, capital and the state will use this moment to find a balance that lets us prosper together.”

The scholar said the carmaker’s 2028 target may already represent a compromise — a way to “test the waters” with unions and the public — rather than the earliest date it could realistically roll out AI robots at scale. Recent advances showcased at events such as CES, he added, suggest the technology is close to deployment readiness.

“The conditions for rapid change are already in place,” he said. “Since Hyundai Motor raised the flag, companies in China and the U.S. will not sit still … It will only be a matter of time before fully robotized production systems can be built.”

Tensions are already visible in the rhetoric around the company’s Atlas plan, with the union expressing concerns about a major “employment shock.”

Employers, meanwhile, may be tempted to turn more toward robots. With automation options multiplying and labor rules tightening, some could pursue aggressive restructuring ― a risky move in a country already grappling with tensions over social and economic inequalities. If employers conclude that human labor has become too litigious because of the yellow envelope law, that pressure could harden their resolve to automate, experts say.

But taking such an aggressive strategy would be a costly mistake, said Lee Jong-sun, another professor at the Institute for Research on Labor and Employment.

“We already have tens of thousands of young people who can’t find decent work,” he said. “Manufacturing still provides some of the best stable jobs. If large companies ignore that and focus only on cost, they will face resistance and the country as a whole may end up paying a broader price.”

Both professors said opposing automation outright is neither realistic nor desirable. Robots and AI can take over the most dangerous and grueling tasks, while also improving national competitiveness while peer economies are rearming and reindustrializing. The real task for policymakers is to manage the transition smoothly, they added.

“Korea has the chance to become a test bed not just for physical AI but for a new social model around it,” Ahn said. “If labor, companies and the government can use tools like the yellow envelope law to create a shared strategy instead of a permanent war, Hyundai’s Atlas could mark the beginning of a new kind of prosperity.”

https://www.koreatimes.co.kr/southkorea/society/20260127/yellow-envelope-law-meets-age-of-robot-workers

Posted by Substantial-Owl8342

1 Comment

What will happen when there are no jobs, that make the money for individuals, that want to buy the goods being manufactured?