On a cold night in November 1938, in Hamburg, five-year-old Israel Hirsch stood across the street and watched his world burn. Flames consumed the synagogue where his father prayed, worked, and sang. Fire trucks came, lights flashing, sirens wailing, and then did nothing. They had been ordered not to intervene. That was the night Germany stopped being home.

The synagogue was the heart of the neighborhood. Its dome dominated the street, its doors opening daily to prayer, music, and community. Israel’s father, David Hirsch, was its cantor and executive director. Their apartment stood directly across from it. After Kristallnacht, nothing on that street felt familiar again.

Before the flames, the Gestapo came for his father. David Hirsch had been warned and fled, hoping absence might spare his family. It did not. The message was simple and brutal: return or his family would be taken. He came back.

He was forced to open the synagogue safes as sacred objects and communal treasures were emptied before him. Then he was made to watch as the building was set on fire. The fire brigade stood by. Neighbors watched in silence. No one intervened.

When the synagogue collapsed into ash, something else collapsed with it—the belief that this was a country where Jews could still belong.

Miracle of Escape

David Hirsch was arrested that night and deported to Sachsenhausen. There, Jewish men rounded up during Kristallnacht were beaten, starved, and humiliated. Six weeks later, he was unexpectedly released, saved only by a visa to the United States. As he left the camp, a guard called after him: “When we reach the shores of America, we will destroy every last one of you. Now raus, Jude.”

He came home on the first night of Hanukkah, a miracle born in darkness.

Escape came in fragments. In 1939, the family fled Germany for England, carrying little more than hope and uncertainty. Two years later, Israel’s father left for the United States alone, determined to secure a future for his family. For more than two years after that, Israel, his mother, older brother, sister, and his younger brother waited in wartime England, enduring nightly bombings and the constant fear of what might come next.

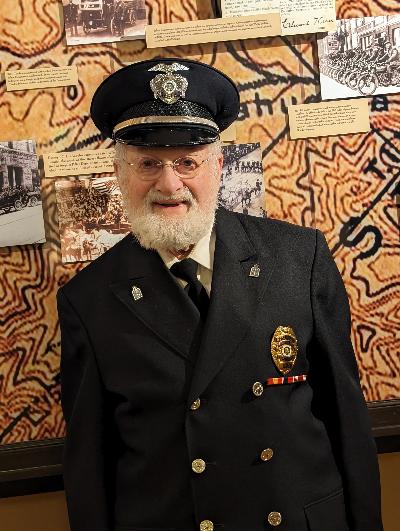

LAPD Chaplain Corps. Rabbi Hirsch is fourth from the left.

LAPD Chaplain Corps. Rabbi Hirsch is fourth from the left.

In desperation, his mother wrote to Eleanor Roosevelt, and, astonishingly, received a reply confirming that they would be permitted to emigrate.

Years later, Israel would recall his mother, Elsie, saying, “Never did I feel God’s presence as strongly as then.”

The family boarded the ship Mauretania, crossing the Atlantic with hundreds of soldiers and refugees. When they arrived at Ellis Island, Israel was just nine years old and America was no longer just a distant promise. It was home.

American Soldier

At 17, Israel Hirsch was drafted into the U.S. Army and sent to Korea. Amid the brutality of war, he kept kosher and put on tefillin daily, acts of spiritual defiance anchoring him to something eternal. Later, because he spoke fluent German, he was stationed in Hamburg, his birthplace, interrogating German soldiers desperate to surrender to American forces rather than fall into Soviet hands. During this period, Rabbi William Greenberg served as the chaplain on the base in Hamburg, and Rabbi Hirsch assisted him closely for several months, an experience that quietly shaped his own future path.

History had come full circle. The Jewish child who had fled Germany returned as a soldier of a free nation.

Back in the United States, Hirsch pursued Jewish learning, earning a master’s degree in Judaic Studies and, eventually, rabbinic ordination in Israel.

He married Phyllis, together raising four children, and today they are blessed with grandchildren and great-grandchildren, having built a life in Los Angeles rooted in devoted service to the Jewish community.

Servicing the Community in LA

As a rabbi and educator, Hirsch worked quietly, but relentlessly to protect Jewish life. As part of the Los Angeles Crisis Response Team, and later as a chaplain with the LAPD, he became a bridge between faith and civic responsibility. He ensured police understood Jewish holidays, Shabbat mode, and the vulnerability of families walking to synagogue. Increasing crosswalk timing, patrol visibility, simple awareness, his work was driven by partnership.

In the early 2000s, he joined the LAPD Chaplain Corps as a volunteer, serving officers of all faiths. He comforted families after sudden deaths, stood beside officers facing moral injury, and brought quiet presence into moments of unbearable loss. Chaplains trained with psychologists, learned how to speak to grieving parents, attended roll calls, rode along on patrols, and simply showed up, again and again.

For this work, Rabbi Hirsch received numerous honors, including the LAPD’s Saint Michael Award for Chaplain of the Year. But titles never mattered to him.

Even after suffering a stroke in his nineties, he continued visiting his station, attending ceremonies, and bearing witness.

Even after suffering a stroke in his nineties, he continued visiting his station, attending ceremonies, and bearing witness.

Asked what it takes to be an LAPD chaplain, Rabbi Hirsch offers a deceptively simple answer: “You have to be an erliche person, a person of integrity. Someone who does not judge.”

That quiet definition is his legacy.

Rabbi Israel Hirsch did not measure his life by what he endured, but by how he responded. It is a blueprint for moral courage, how trauma can be transformed into service, how faith becomes responsibility, and how memory demands action. His life conveys a deeply Jewish truth: to remember is not enough. We are responsible for what we do with that memory.

In a fractured world, that responsibility has never mattered more.