Often when we think about photographs, we don’t even think about the painful stories that may be hidden behind them, since most of the time they simply sit on shelves and drawers, carefully preserved, representing a very painful and often final connection with a loved one during the recent war in Kosovo.

It was precisely this thought that became a main impetus for me to start writing this article, and to show that the story of a photograph can have a great significance not only for us as an audience, but also for the families of persons missing during the war, since in the absence of documents or official evidence, they turn these memories into symbols of remembrance for their loved ones.

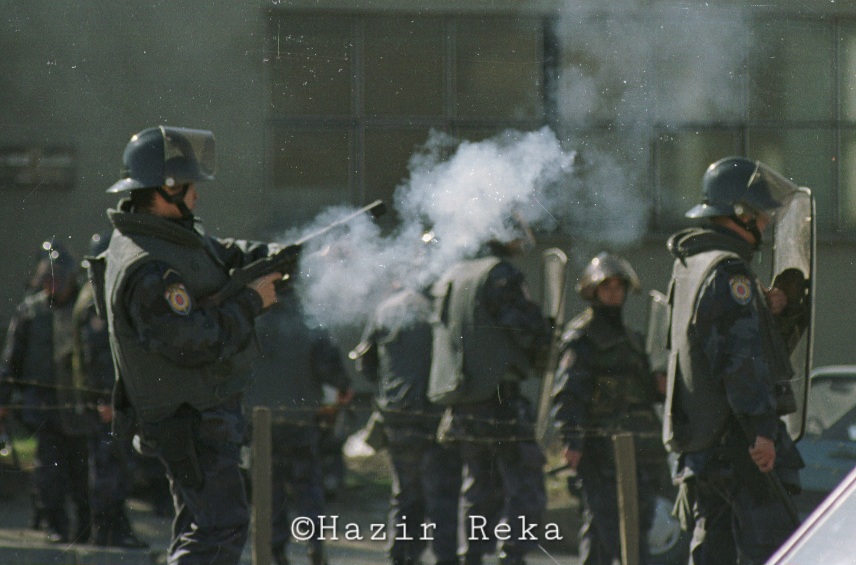

My curiosity to understand more about this topic led me to a conversation with a man who documented these moments in real time – photojournalist Hazir Reka.

NATO helicopter carrying the German defense minister Franz Josef Jung lands at peacekeeper’s headquarters in Kosovo capital Pristina, February 20, 2008. NATO thwarted overnight a bid by Kosovo Serbs to assert their authority in a northern slice of the newly independent republic, restoring control on the border with Serbia where crowds had burned down two crossing points. REUTERS/Hazir Reka (KOSOVO)

NATO helicopter carrying the German defense minister Franz Josef Jung lands at peacekeeper’s headquarters in Kosovo capital Pristina, February 20, 2008. NATO thwarted overnight a bid by Kosovo Serbs to assert their authority in a northern slice of the newly independent republic, restoring control on the border with Serbia where crowds had burned down two crossing points. REUTERS/Hazir Reka (KOSOVO)

Reka is known for his work, as he has witnessed many painful moments during this period, and has documented very important moments through his work.

According to him, photographs should be preserved as private memories, but some of them that have historical value should be archived in public spaces.

“For years, people have been taking photos of various parties, objects, and people that may no longer exist today. They have historical value and should be preserved as evidence,” he says.

Reka also highlights the difficulties he faced during the early days of his career as a young photojournalist, with the main challenge being the lack of adequate equipment to document the events of the time. One specific event he remembers having problems with his equipment was the Recak massacre.

The Kosovo Protection Corps of former guerrillas carries a coffin past grieving relatives at the funeral of 13 ethnic Albanian victims of the 1998-99 Kosovo war, October 6, 2006. Their remains were found in mass graves in Serbia and returned to the United Nations-run province this year. The burial took place in Kosovo Polje, just west of the capital Pristina. REUTERS/Hazir Reka (SERBIA AND KOSOVO)

The Kosovo Protection Corps of former guerrillas carries a coffin past grieving relatives at the funeral of 13 ethnic Albanian victims of the 1998-99 Kosovo war, October 6, 2006. Their remains were found in mass graves in Serbia and returned to the United Nations-run province this year. The burial took place in Kosovo Polje, just west of the capital Pristina. REUTERS/Hazir Reka (SERBIA AND KOSOVO)

“When the Recak massacre happened, I went to the scene much earlier, and I had a problem with my camera, because it was old equipment, but with the help of my fellow photographers I avoided the problem. You can imagine not having those very important photos, considering the risk of getting there, where along the way there was a possibility that anything could happen and you would return without photos,” he recalls.

Regarding the role of photography in reconciliation and documentation, Reka indicates that despite his efforts together with his colleagues to preserve important materials, institutions have not been careful regarding this aspect.

“From 1984 until today, I have followed many events such as: protests, demonstrations, the war, refugees, their return from different countries where they were, and for me the chronology of events throughout these years is important. Although the state has not been careful enough in archiving them – I am talking about my photographs and those of my colleagues, but maybe the time has come,” says Reka.

Family members weep at the funeral of 13 ethnic Albanian victims of the 1998-99 Kosovo war, October 6, 2006. Their remains were found in mass graves in Serbia and returned to the United Nations-run province this year. The burial took place in Kosovo Polje, just west of the capital Pristina. REUTERS/Hazir Reka (SERBIA AND KOSOVO)

Family members weep at the funeral of 13 ethnic Albanian victims of the 1998-99 Kosovo war, October 6, 2006. Their remains were found in mass graves in Serbia and returned to the United Nations-run province this year. The burial took place in Kosovo Polje, just west of the capital Pristina. REUTERS/Hazir Reka (SERBIA AND KOSOVO)

On the other hand, institutions say that there is already an institutional effort to document this visual evidence. According to the Institute of War Crimes in Kosovo, there is a state archive, where materials containing strong evidence about the recent war in Kosovo are documented and stored.

“The creation and functioning of this archive is based on Article 5 and Article 7 of Law No. 08/L-145, where the Institute is given the mandate to collect, process, store and publish data on crimes committed during the war in Kosovo. The archive includes photographs provided by family members, NGOs, local and international institutions, as well as open public sources. These photographs are catalogued according to verification protocols and are part of the documentation files of crime cases”, emphasizes Drilon Selmani from the Institute of Crimes Committed During the War in Kosovo.

Selmani also emphasizes the value and importance that the Institute places on family photographs in the absence of official documents, since according to him, these photographs play a very important role in the documentation process.

“The Institute considers them as supporting evidence with historical, emotional and documentary value. They help in identifying victims and confirming their presence at certain times and places. In some cases, the photographs have been used as part of documentary files submitted to justice institutions, where they serve as a supporting element for other testimonies and facts in investigative or judicial processes,” Selmani added.

However, according to Selman, the entire process of collecting and documenting these materials and evidence is not easy at all because they face a variety of challenges, ranging from the lack of information and data, legal responsibility for verification, to the risk of manipulation of this evidence.

Currently, the Institute for War Crimes in Kosovo has collected around 20TB of digital material, 320 meters of physical material, and over 900 book titles in their library, while regarding the issue of missing persons, they are in the process of officially preparing the data.

In conclusion, even though 26 years have passed since the last war in Kosovo, war crimes still remain alive among us, so they do not become obsolete over time, and it is precisely the numerous photographs from this period that have served as living evidence of this bitter time. Even though time has passed, justice institutions continue to prosecute and solve war crimes cases. /Sara Mulliqi/ Telegraph/

This article is a product of the Academy for Reporting in the Field of Dealing with the Past (BmK) and Conflict-Sensitive Journalism, implemented by the Pro Peace Program in Kosovo and the Association of Kosovo Journalists – AGK. The views expressed in this article are the responsibility of the journalist and do not in any way reflect the views of Pro Peace and AGK.