In a piece called October 7: The Return of History, which I wrote for the Jewish Review of Books some time ago, I wrote that

The purpose of Zionism … was to rewrite [Jewish] history, or at least its narrative arc. Zionism wasn’t about denying Jewish history—it was about altering it. … American Jews did not imagine that they could change Jewish history; they thought they could dodge it. As Saul Bellow put it in Humboldt’s Gift, Humboldt—a midcentury American poet who was the son of a Jewish Hungarian immigrant father—believed that “history was a nightmare during which he was trying to get a good night’s rest.”

Those radically different attitudes to history are, I still believe, one of the core divides between American Jews and Israelis. It’s difficult to describe the degree to which history infuses such a wide swathe of what gets discussed in Israel. A country founded out of the ashes of the worst of atrocities, and a country in which some of those who fought in the War of Independence are still alive, is bound to be history-infused. The fact that Jewish tradition (genuine Jewish tradition—not bagels and “tikkun olam”) is also deeply fixated on history only adds to that.

It is this fixation on history that so struck me about a recent Facebook post by Nissimmi Naim-Naor. There have been countless pieces written about the recent American election in the Israeli press, and a lot on social media, too. There have been predictions of an impending American Jewish wave of aliyah (a silly notion that is not going to happen—think German Jews), more serious discussions of what the poor Republican showing across the country suggests for Israel, which has fashioned its foreign policy on the assumption of continuing dominance of the Christian right, and much more.

Nothing, though, struck me as being as thoughtful—or as uniquely Israeli—as this post, which is VERY long, and AI-translated in full below. On his website, Nissimmi Naim Naor describes himself as “a chef who brings memory, culture, identity, and tradition to life through the art of food—especially carbs. Blending culinary creativity with Jewish heritage, Nissimmi crafts workshops that nourish both body and soul, fostering connection, learning, and community.”

In a more complete bio, also on his site, he describes himself as follows:

Nissimmi is a chef, ordained rabbi, educator and speaker, who blends his love of food and people with his commitment to building connections through culture, Jewish identity, and tradition. He is the creator and TV host of A Pot of Longing, as well as Shalom Hartman Institute’s People of the Cook: Your Kitchen as a Beit Midrash.

While based in Israel, he frequently travels to North America and Europe to lead intimate culinary events, large-scale workshops, and engaging lectures. Known for his magnetic personality and genuine love for meeting and feeding people, he brings a unique warmth and depth to every event he hosts.

…

Beyond the kitchen, Nissimmi holds degrees in philosophy, economics, political science, and law. He received his rabbinical ordination from the Hartman Institute and serves as a Casualties Notification Officer in the IDF reserves, having dedicated over 200 days to this role since October 7th.

Nissimmi lives in Jerusalem with his wife, Shlomit, and their three daughters. He also leads the Siah Yitzhak congregation in the Katamon neighborhood.

I suspect that many of our readers are not yet familiar with him, which I hope will change with today’s post.

Note, by the way, the first comment below his post, written by his wife:צריך להכין קפה לפני שקוראים את זה. שחור חזק. “You need to make yourself a coffee before reading this. Black and strong.” (The kind of comment that only a spouse can make!)

It is, indeed, long, but it is also hugely important. I hope you’ll take the time to read what he has to say. Below his post, I’ve attached an article from The New York Times in 1934 which, I think, adds even more resonance to what Naim-Naor writes:

I devoted a significant portion of my undergraduate degree to Herzl, this giant of a Jew who in less than ten years took a scattered and divided people and turned them into a massive mass movement that ultimately led to the establishment of a state for the Jewish people. But with your permission, I want to begin with the moment before, when Herzl was not yet Herzl.

There is today a fairly sweeping consensus among Herzl scholars, which becomes sharper when reading his diaries, that the formative event of his life in the Zionist context was not the Dreyfus trial, but rather the rise of Karl Lueger to the leadership of Vienna’s city council. Who is Karl Lueger? Well, a short history lesson:

Mid-19th century, the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Emperor Franz Josef gives the Jews what had until then been an absolute fantasy in most of Europe—full equal civil rights. As in all other places where this happened, Jewish talent, genius, and devotion proved themselves, and about fifty years later (Franz Josef still the emperor), the Jews in the Austro-Hungarian Empire become a cultural and economic force that cannot be ignored. The empire’s capital, Vienna, becomes one of the most important and powerful Jewish centers at the end of the 19th century, with Jewish bankers, philosophers, journalists, doctors, artists, and businessmen. The Jews gain full equality, enormous respect, and many of the magnificent houses on the Ringstrasse, the most prestigious street in Vienna that was built on the ruins of the ancient wall—belong to Jews. Vienna is a Jewish city, strong, proud, and self-confident.

This Jewish idyll is rudely disrupted in the elections for mayor held in 1895, in which after years of direct appointment by the emperor, democratic elections are held (open of course only to men with education and property, but that’s another story) for the mayoralty of Vienna—and the elected mayor is Karl Lueger. Vienna undergoes major changes in these years, with massive immigration from Eastern Europe that changes the social and cultural fabric of the city, whose streets suddenly hear much more Yiddish and Czech, and Lueger is elected on a platform that calls for returning Vienna to the real Viennese, not allowing schools that teach in languages other than German, and also limiting the number of Jews in journalism. Karl Lueger is of course fully antisemitic, and openly so (one Adolf Hitler even mentions him in his biography as a source of inspiration for antisemitism from the period he lived in Vienna), and when he is elected Jewish Vienna is shocked. The emperor is unwilling to accept his election and orders repeat elections that end—surprise, surprise—in Lueger’s victory. The emperor refuses to accept his election the second time, and the third and fourth times, and the fifth time Lueger is elected the emperor has no choice left, and in 1897 Karl Lueger, a declared antisemite, is appointed to head Vienna’s city council.

During this saga, on June 8, 1896, Herzl writes in his diary that this is the beginning of a St. Bartholomew’s Night descending upon Europe; and this rupture, of seeing the wealthy and powerful Jews of Vienna frightened about the future, while they try to calculate whether the emperor’s cancellation of his election is good or bad for the Jews, leads Herzl to take action and begin a process that will end fifty years later in the establishment of a Jewish state in the Land of Israel.

Bill Clinton won the 1992 elections riding on the slogan “It’s the economy, stupid,” which expressed American disgust with magnificent achievements in foreign policy—when the average American struggles to get through the month. Similarly, Zohran Mamdani—a New Yorker, son of an upper-class Muslim family, 34 years old, is about to win the upcoming elections for mayor of New York riding on the pain of young New Yorkers living hand to mouth, who see how the city where young Leonard Cohen, Paul Simon, and Bob Dylan rented apartments for pennies so they could make art, is becoming a city of multimillionaires only, where young people who aren’t doctors, lawyers, or venture capitalists simply cannot live. Mamdani’s policy can be summarized by saying he’s for everything good (affordable housing, employment, free public transportation, and LGBTQ rights) and against everything bad (the rich, police, and corruption); oh yes, he’s also against Israel as a Jewish state, refuses to call Hamas a terrorist organization, promised he would arrest Netanyahu when he arrives in New York, and was filmed two years ago instructing his activists to explain to those they speak with that “when they feel the boot of the NYPD on their neck, it’s the IDF that tied the laces.”

By the way, much of Mamdani’s campaign includes food, and he’s photographed eating in places he seems to know well, and that New Yorkers love to eat at; and he’s charismatic, smart, photographs excellently—and according to friends of mine who met him for one-on-one conversations—also an amazing conversationalist and very attentive. It must be admitted honestly that he devotes most of his campaign to the issues that are most burning for the average New Yorker—rent, the education system, and public transportation; he’s running against Andrew Cuomo—a Democrat from the heart of the establishment, wealthy, older—and a serial sexual harasser; and many of those about to vote for him say they’re choosing him despite “his problematic views on Jews and Israel” because he promises to fix the things that bother them in their city.

If you ask me personally, I believe Mamdani is a kind of Ben Gvir. Just as every time Ben Gvir says something terrible and then says “I said terrorists, not Arabs” it’s still clear to me that at the end of the day, at home, when he takes off the mask and tie—he’s the same racist Arab-hater; regarding Mamdani too it’s clear to me that despite his hiding behind “just” anti-Israeliness and concern for Palestinians, and the fact that he has Jewish activists and friends, at the end of the day, at home—he’s a real and very sophisticated antisemite who will never admit it publicly. One doesn’t have to agree with me of course, and Mamdani indeed invests much effort in reassuring New York’s Jews (about twenty percent of the population, and far beyond those twenty percent of the city’s capital, culture, and economy) and explaining that he will always be there for them.

Many of New York’s Jews, from the right and left, are terrified of his likely election as mayor; and conduct among themselves discussions about what Trump will do if Mamdani is elected, and families are torn apart over the choice of young Jews (who grew up in wealthy homes with parents who would never vote for an anti-Israeli Muslim who calls for taxing the rich) to vote for Mamdani.

On one of my visits to New York a little over a year ago, I sat for coffee with an American friend who is a rabbi, an amazing educator, and very Zionist. While we’re talking about the war, about the bubbling antisemitism, and about this young man trying to get elected mayor, she said a sentence that stunned me: “People tell themselves, it won’t happen here, here we’re really strong, here we have money and power and we’re the elite of this country—and these people simply haven’t studied enough history, and don’t know how strong we were in Madrid, in Vienna, in Rabat, and in Amsterdam—until everything turned around.” Her words have stayed with me since, and particularly on every visit to the US, where I heard from Jews about more and more hair-raising antisemitic incidents they experienced—including attempted attacks on their synagogues; and I saw more and more anti-Israeli (with or without swastikas) and anti-Jewish graffiti.

Personally, the fact that the next mayor of the largest and strongest Jewish city in the world is going to be (probably) fully antisemitic reminds me of the election of Karl Lueger to head Vienna’s city council. It’s a moment when the Jewish elite of the city understands that it’s not as strong as it thought, and in a very frightening way—also not as at home as it thought.

This is a moment when the Jewish elite of the city understands that it’s not as strong as it thought, and in a very frightening way—also not as at home as it thought.

Jewish journalist Franklin Foer published an article a year and a half ago in which he declares the end of the golden age of American Jewry, and since then I’ve heard this declaration repeated again and again—in salon conversations, coffee shops, and synagogues; and it’s a terrifying feeling. It’s clear to me that as mayor, Mamdani won’t want attacks against Jews in his city; but the ripple effects of the anti-Israeli and anti-Jewish sentiment are felt well throughout the United States. When Barack Obama publicly commits to be there and help Mamdani, it’s not far-fetched to assume that at some point in the next two decades the United States will have an anti-Israeli and perhaps also antisemitic president, and this is a new and terrifying reality that threatens Jewish existence in the United States, and let’s be honest—also in Israel (the situation in the Republican Party, in case you were wondering, is no less threatening).

About the responses of New York’s rabbis to this event one could write an entire (and fascinating!) book that would deal with establishment politics, nonprofit laws, and the tension between being an elite and the painful understanding that you’re not the government; but the rabbinical response I want to quote here is that of Rabbi Angela Buchdahl, who on one hand made clear how dangerous this moment is for New York’s Jewish future, and on the other—that we have, as Jews, difficult existential problems that accompany us and will accompany us even after these elections—and the most important thing is our togetherness. We cannot afford to disqualify, ostracize, or distance people from us because of who they voted for, and we must be united in the face of the challenges before us.

In the past two years I’ve told every American Jewish group I’ve met how significant their support for us after October 7th was, and that we promise never to forget it. The first step on this path will be to remind them that we’re there with them now too, and ready to support them in any way they need.

Unlike the days of Karl Lueger, and thanks to the work and self-sacrifice of a Viennese journalist who was shocked by his election—now Jews also have a home of their own.

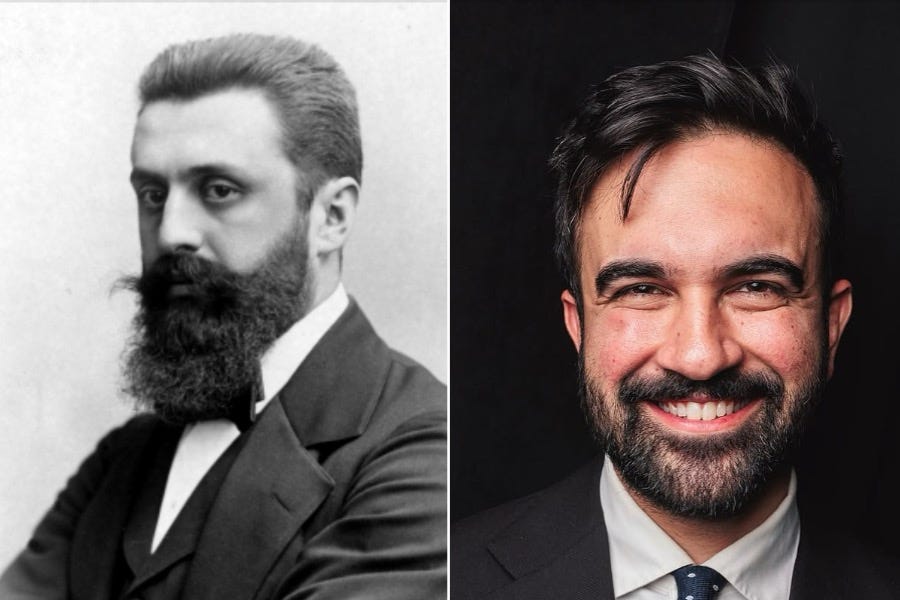

(In the picture: a Viennese journalist who believed in the power of dreams, and an American politician with other dreams)