The number of taxa reported in this study was 50 (from 23 mycological families); among these, six were identified at the genus level, four at the section level, and the remainder at the species level. All the taxa determined at the section level and five at the genus level are considered ethnotaxa (see the ‘Fieldwork methods’ subsection). The complete dataset of the recorded useful WMs in Andorra is available in the Supplementary material.

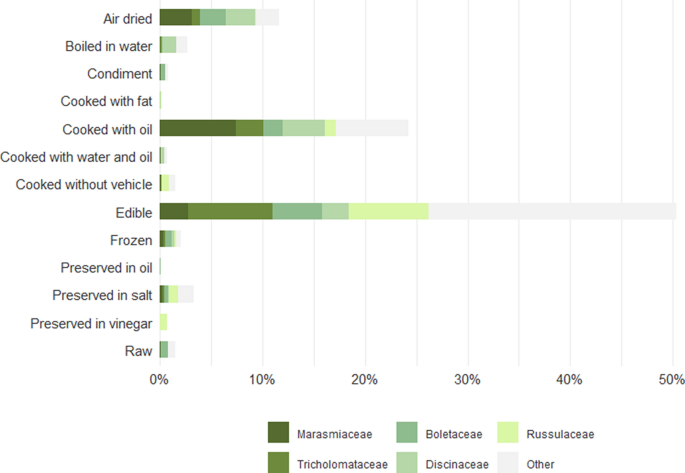

The five most-cited families are Marasmiaceae (14.25%), Tricholomataceae (12.29%), Russulaceae (11.60%), and Boletaceae and Discinaceae (11.35% each). The high representation of these families is unsurprising, as they include six out of the ten most frequently cited taxa. On the other hand, the most representative family was Tricholomataceae, with eight taxa, followed by Agaricaceae and Hygrophoraceae, with five taxa each.

The informants provided a total of 1,172 URs from 42 useful taxa (among the 50 total taxa), nine URs (0.77%) corresponding to medicinal uses, 1,142 URs (97.44%) corresponding to food uses, and 21 URs (1.79%) corresponding to other uses. The numbers show that a large amount of information was recorded for food uses, and traditional medicinal uses or other applications for WMs are less reported; however, we are convinced that it is important to record them. Industrialized countries have undergone acculturalization, that is, a form of more or less intense erosion of knowledge, traditionally passed down through generations [59]. This process affects many ethnobotanical prospections, and as previously mentioned, it is also evident in ethnomycological studies, which appear even more vulnerable, as reflected in the results obtained.

This ethnomycological approach in the territory lays the groundwork field and highlights the need for future research to focus more deeply on lesser-known or underreported uses, such as medicinal applications. Why is the medicinal use of WMs less widespread than that of plants in Andorra? While the reason remains uncertain, the most frequently reported use is culinary, whereas other uses, such as medicinal or economic uses (the latter, implying that WEMs are sold, in fact also related to food use) are only occasionally mentioned. This trend has also been observed in other ethnomycological studies, where medicinal uses constitute a minority and are typically limited to specific uses [1]. In contrast, recent scientific studies have highlighted the significant medicinal potential of mushrooms, prompting renewed interest in their investigation [60]. However, the traditional knowledge surrounding these organisms (largely preserved in the memories of older generations and scarcely practiced by younger adults) is at risk of disappearing due to climate change, anthropogenic pressures, and socioeconomic transitions prom primarily to secondary and tertiary activities [60].

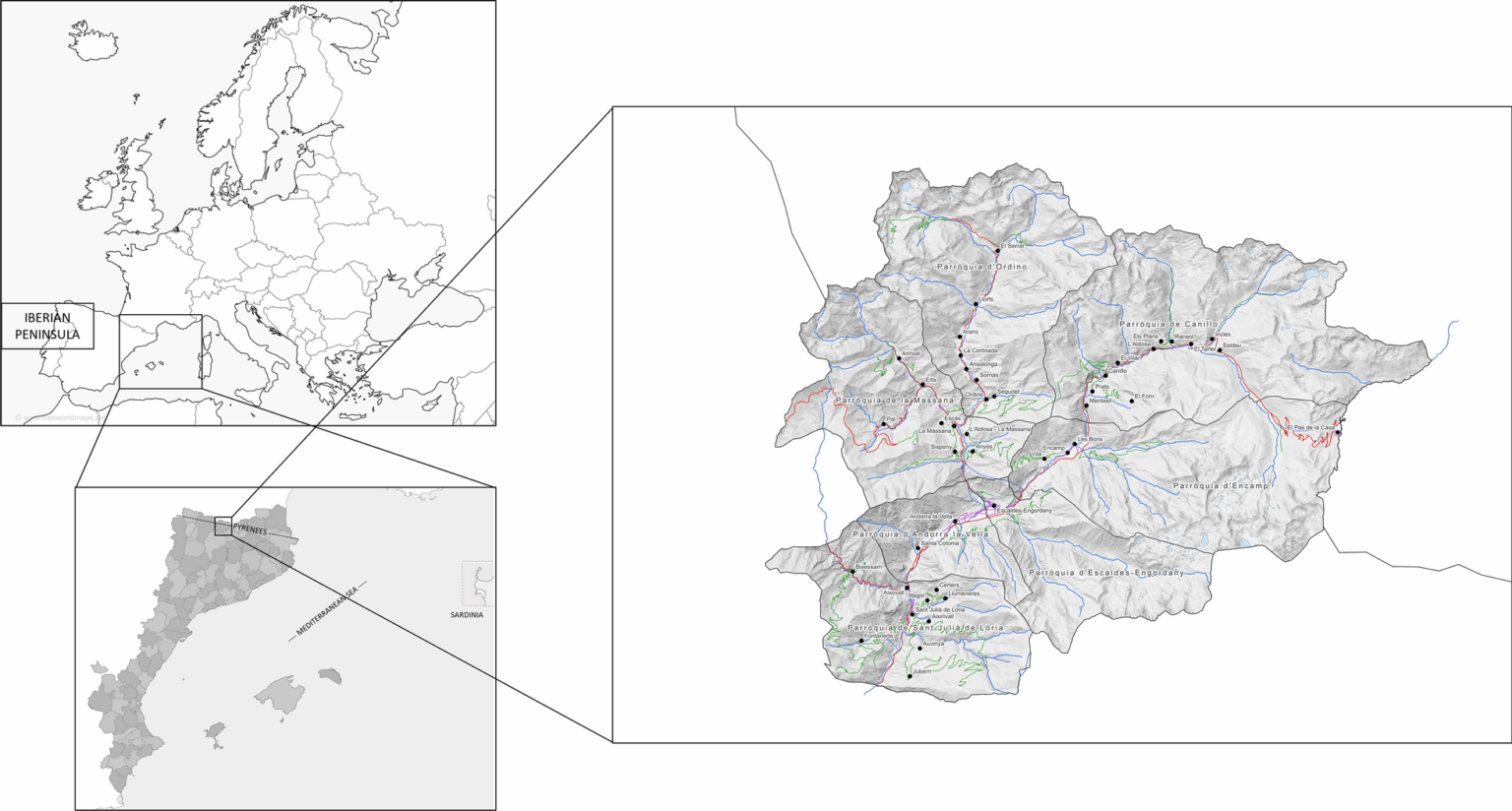

Table 1 presents the number of taxa mentioned in various ethnomycological studies worldwide, offering an overview of the data provided by these studies. We can observe that, in general, the number of WMs traditionally used is not very high and, even if it is not exhaustive, since we chose some works from geographically distant places as examples, our results from Andorra are among the very highest recorded in terms of total taxa and the highest of all as per food taxa. Notably, the territory with more useful WMs recorded [1] is in the same Iberian Peninsula, where Andorra is located. Ethnomycological prospections often highlight only a limited number of taxa. For example, in the Catalan linguistic area (CLA), a region composed of multiple territories, including Andorra, 643 taxa have been documented as edible mushrooms [57]. Similarly, in Mexico, 425 WEMs have been cited as being traditionally consumed [57].

General quantitative ethnomycology

To assess the state of ethnomycological knowledge in the area and establish some parameters for further comparisons, we calculated the FIC of our total prospect, which was 0.96. This value, which is very close to the maximum of 1.00, indicates a high level of agreement among the informants regarding the use of WMs, suggesting that the dataset is consistent and culturally cohesive in the studied territory. This very high value ultimately accounts for the robustness of the dataset obtained. We calculated the FIC for culinary uses (0.96), the same strong value as the general index. With respect to medicinal and other uses, the FIC value provides a nonsignificant, negative result, since there are few reports of these kinds of uses.

The ethnomycoticity index (EMI), calculated via an estimation of 2,000 WMs in the territory [22], is 2.05%, which means that less than 5% of the macromycetes present in the territory are known or used by the informants. It is not possible to compare EMI with other territories because the works do not indicate any estimation of the mushroom diversity of the territories studied. We considered the ethnobotanicity index (EI) [11] as the equivalent in plants, and we provide some examples. In the surrounding region of Alt Urgell (Catalonia), the EI was 26.63%, which is comparable to that in other Catalan areas, where a quarter of the native plants are typically recognized by their local names and traditional uses [72]. As shown in Table 1, the number of WMs taxa reported is usually low, meaning that EMI values, compared with those of plants, always represent a lower value. There is still much research to be done in the field of ethnomycology and in understanding the mycodiversity of Pyrenees. However, we believe that this new index could be a useful tool for comparing different territories and may serve as a foundation for future studies. When comparing plants and fungi, it is important to consider that the number of macromycete species is greater than that of plants and that their phenology, scarcity during dry years, and cultural factors (such as distrust and caution) significantly influence their use.

Medicinal uses

The total number of taxa used for medicinal purposes was five, of which only one report was dedicated to veterinary use, and the rest were for human use. The nine use reports were reported by nine informants, each referring to one taxon. Moreover, information about the four medicinal mixtures was also collected (Supplementary material).

Lycoperdon perlatum Pers. is the most cited taxon (five URs), followed by Claviceps purpurea (Fr.) Tul. (two URs), and Marasmius oreades (Bolton) Fr. and Ramaria spp. are cited one time each. Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Desm.) Meyen has been reported as a medicinal taxon only in mixtures. Although it is not a WM species, as it is a micromycete, we decided to include it because some informants reported past medicinal uses.

Lycoperdon perlatum has been reported as a vulnerary antirheumatic agent for the treatment of meningitis. The fruiting body can be used directly, but spores can also be applied for skin disorders. Vulnerary use was also reported in Fajardo et al.’s ethnomycological study [1], as skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders are frequent when working in hills, and in Catalan theses from the Garrigues [73] and Pallars [74] districts. The veterinary application of this taxon has also been reported, such as its direct use of spores to treat ulcers and wounds.

The use of sclerotia produced by C. purpurea as a labour coadjuvant was reported twice. Niell et al. [75] documented the use of C. purpurea in Andorra and Alt Urgell (Catalonia), noting that its sclerotia were used by midwives as a labour coadjuvant. Some informants vaguely remember the preparation of a tisane, but details such as the quantity of sclerotia used or the precise timing of administration were not transmitted. Additionally, the limited transmission of this knowledge may be related to both a general unfamiliarity with the species in Andorra and the secrecy traditionally maintained among midwives (which constitute restricted knowledge). This secrecy, likely due to the sensitive nature of its use, contributed to the loss of detailed knowledge, which appears to have occurred in the last century with the modernization of the country. Furthermore, Illana-Esteban [76] described alkaloids from sclerotia and their uses in current traditional medicine. In addition, eating cooked M. oreades has been reported to have an intestinal anti-inflammatory effect, and eating cooked Ramaria spp. in small amounts is considered depurative and can help with constipation.

Finally, with respect to medicinal mixtures, L. perlatum, C. purpurea and S. cerevisiae taxa were reported for four preparations. Lycoperdon perlatum mixed with Lilium candidum L. tepals has been reported to be used twice as an antirheumatic agent and for burns or scalds. Claviceps purpurea was reported with Saxifraga longifolia Lap. as a labour coadjuvant. Finally, to constitute an anthelmintic plaster, S. cerevisiae was added as a binder, together with Artemisia absinthium L., Juniperus oxycedrus L. and N. tabacum.

Food uses

In the studied area, 39 taxa consumed as food for self-consumption were identified. Among the 1,142 URs provided by 127 informants, 99.04% were reported to be consumed by humans, and 0.96% were consumed by animals (Supplementary material). The mean number of WEMs cited per informant is 7.22, with 28 taxa being the maximum reported by one informant and one the minimum. We reported that 79.49% of the taxa had the same use by at least three informants. According to Grand & Wondergem [77] and Johns et al. [78], such repeated use reports may indicate the robustness of the information, which can be useful for identifying promising candidates for further research and the potential development and commercialization of new products, whether medicinal, as treated by the quoted authors, nutritional, or otherwise of general interest [52]. The frequency of mention is also a key parameter in assessing the cultural significance (CS) of an organism, which refers to the perceived importance or role that the organism plays within a particular cultural context. For WEMs, Garibay-Orijel et al. [79] developed the edible mushroom cultural significance index (EMCSI), which includes seven cultural variables. In this study, we were unable to calculate this index, as it would have required more specific data than what was collected during our prospecting. We acknowledge the relevance of this metric, which has been applied in previous studies, such as those by Alonso-Aguilar et al. [80] and Ruan-Soto [81], and intended to incorporate it into the Andorran dataset as more comprehensive data become available.

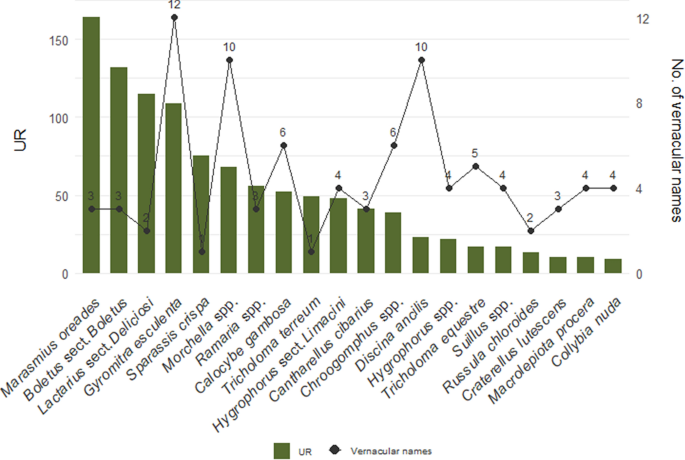

The five most cited species are M. oreades (164 URs; 14.36%), Boletus sect. Boletus L. (132 URs; 11.56%), Lactarius sect. Deliciosi (Fr.) Redeuilh, Verbeken & Walleyn (115 URs; 10.07%), G. esculenta (109 URs; 9.54%), and S. crispa (75 URs; 6.57%). To consult the taxa included in the sections, see Additional file 1 (Ethnotaxa established in the studied area), as explained in the ‘Fieldwork methods’ subsection. Sparassis crispa is among the most cited WEMs of Andorra since it is considered a good WEM and highly valued by those who know it [82] but is not reported as one of the most commonly known WEMs in neighbouring regions, as it is not even included in the guide ‘101 Bolets de Catalunya que cal conèixer’, in English ‘101 Mushrooms of Catalonia you should know’ [83]. In addition, S. crispa creates strong emotions in informants since eating them is considered a reward for the effort and luck of having found them (see the ‘Other uses’ subsection).

The top 20 taxa, which represent 93.61% of the URs, and their principal modes of consumption are shown in Table 2.

The consumed part of WEMs is always the fruiting body, the only part of the mushroom visible in macromycetes. As in other recent works, we also noted a preference for the use of visibly large mushrooms that grow on land [68].

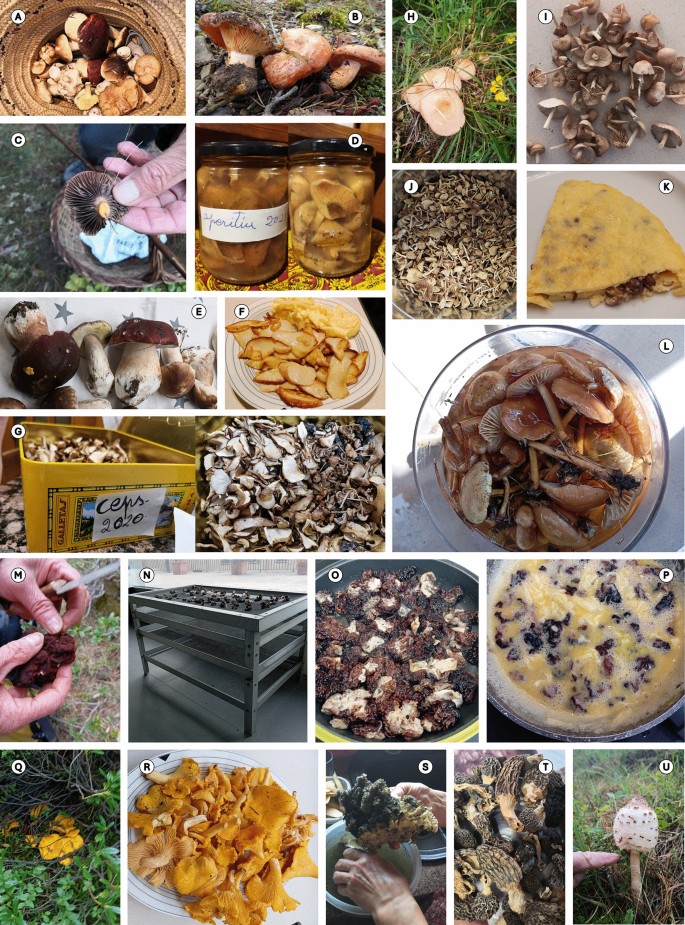

Among the 1,142 URs, 47.28% reported a preparation (336 URs; 29.42%) or preservation (204 URs; 17.86%) method. For 50.35% (575 URs) of the cases, the mushrooms were reported only as edible, and for 2.37% (27 URs), the WEMs were eaten raw or used as condiments. See Fig. 2 for a detailed breakdown of URs by food category and Fig. 3 for visual examples of different preparation and conservation methods applied to WEMs.

Representative images of wild edible mushrooms (WEMs) documented in this study, showing them in different contexts. B, H, Q in their natural habitat; A, C, M, S, U picked by the informants; E, I, R fresh—recently harvested; D, G, J, N, T with a conservation method applied; L rehydrated post air drying/precooking; F, K, O, P with a preparation method applied. The spices depicted include the following: A mixture of WEM; B Lactarius deliciosus; C, D Lactarius sect. Deliciosi; E, F Boletus sect. Boletus; H–L Marasmius oreades; M, O-P Gyromitra esculenta; N Paragyromitra infula; Q, R Cantharellus cibarius; S Sparassis crispa; T Morchella spp.; and U Macrolepiota procera

Outlining the preparation methods, there are five categories. The most cited WEMs are cooked with oil (277 URs; 24.26%), mainly to specify that the WEMs are prepared in a stew (168 URs; 14.71%) or for an omelette (88 URs; 7.71%), principally with M. oreades or G. esculenta in both cases.

With respect to preservation methods, air-drying WEM was the most commonly used method (133 URs; 11,65%), followed by preservation in salt (38 URs; 3.33%) and the modern freezing technique (24 URs; 2.10%), where Boletus sect. Boletus is the most cited taxon.

Air drying remains the most common method of preserving WEMs; M. oreades (36 URs), Boletus sect. Boletus (29 URs), G. esculenta (25 URs) and Morchella spp. (16 URs) are the mushrooms most commonly reported for air drying. However, species from Lactarius sect. Deliciosi cannot be air dried and are typically preserved in vinegar alone as appetizers or in salt. Notably, only taxa preserved in vinegar alone were recorded. Other preservation methods reported will be more relevant when elaborating mixtures (see the next subsection, ‘Food mixtures’). Gyromitra esculenta, Boletus sect. Boletus, and M. oreades can also be preserved by freezing; a more modern technique that is increasingly replacing air drying as a preservation method, since it is more accessible and less time-consuming.

Eating raw WEMs was reported in 1.58% (18 URs) of the culinary data. All the raw reports on human consumption (7 URs; 0.61%) referred to Boletus sect. Boletus to prepare a salad or a carpaccio. The remaining 11 URs (0.96%) referred to animals that consumed Boletus sect. Boletus, M. oreades, S. crispa, or Tuber melanosporum Vittad. Informants often describe animal feed as problematic, since these WEMs are highly valued, and their consumption by animals prevents the informants from harvesting them.

In addition, Boletus sect. Boletus, Craterellus lutescens (Fr.) Fr., M. oreades, and T. melanosporum were reported as condiments (9 URs; 0.79%). The first three are usually pulverized and added to many different traditional dishes. Tuber melanosporum, which is one of the most valued mushrooms in haute cuisine, is employed as a condiment to prepare a truffle-infused cognac or a pâté. We believe that these last two reports show a strong French influence.

Given the growing interest and demand for WEMs and their frequent use and reporting, we propose several candidates for nutritional analysis, as their values have not yet been studied, as reported in Álvarez-Puig et al. [57]. Nutritional values are essential for promoting the distribution and consumption of wild species, as these species may offer significant benefits in terms of nutrition, sustainability, and the conservation of biocultural heritage [84]. Casas et al. [84] reported the nutritional value of wild food plants in the CLA and highlighted their importance. Similarly, we believe that WMs also warrant further study to encourage their safe use, since their nutritional value is important for promoting the distribution and consumption of species. Moreover, this represents a new approach that may contribute additional applications to ethnomycological studies beyond their primary objective of data collection and preservation.

With respect to the ethnotaxa established, some of the taxa included do not have reported nutritional information. In Chroogomphus spp. ethnotaxon, Chroogomphus helveticus (Singer) M.M. Moser and Chroogomphus purpurascens (Lj.N. Vassiljeva) M.M. Nazarova are not analysed; in Hygrophorus spp. ethnotaxon, only Hygrophorus chrysodon (Batsch) Fr. has reported nutritional value, as these ethnotaxa and Hygrophorus sect. Limacini P.-A. Moreau, Bellanger, Loizides & E. Larss. are great candidates for further studies. Finally, Discinia ancilis (Pers.) Sacc. is among the most reported WEMs and is traditionally known as ‘murga d’orella’ (see the ‘Myconymy and its cultural dimension’ subsection), with no nutritional value in the literature. We propose it as a strong candidate to substitute for G. esculenta, which also lacks nutritional information, but owing to their toxicity reports (see the ‘Between poison and tradition’ subsection), we do not consider it a priority candidate.

Food mixtures

In addition to individual WEMs uses, this study inventoried 148 food mixtures with plants and fungi (Supplementary material). All the plant and fungal taxa were jointly analysed in relation to the food mixtures.

With respect to WEMs, 20 taxa have been reported, with Lactarius sect. Deliciosi (57 URs; 8.52%), Boletus sect. Boletus (30 URs; 4.48%), and M. oreades (16 URs; 2.39%) being the most commonly reported. Among the plants, 19 taxa included Olea europaea L. subsp. europaea var. europaea (133 URs; 19.73%), Allium sativum L. (96 URs; 14.35%), Vitis vinifera L. (65 URs; 9.72%), and Piper nigrum L. (57 URs; 8.52%), the most reported plants used as vehicles for preservation (olive oil or vinegar) or as condiments of mixtures (garlic or pepper). The mean number of species reported in food mixtures is 4.00, with the highest number being 12 species in a single mixture and the minimum required to constitute a mixture being two.

Cooking with oil is the main use reported (182 URs; 27.20%), followed by preservation in vinegar (158 URs; 23.62%), in oil (102 URs; 15.25%) or in oil and vinegar (97URs; 14.50%). In general terms, a 57.10% (382 URs) corresponded to preservation methods, and 40.81% (273 URs) corresponded to cooking methods. For the remaining percentage, 1.79% (12 URs) corresponds to Boletus sect. Boletus eaten raw as a salad with olive oil (O. europaea subsp. europaea var. europaea), pepper (P. nigrum) and vinegar (V. vinifera), and only 0.30% (2 URs) corresponds to a mixture of two WEMs (Boletus sect. Boletus and M. oreades) pulverized together and used as a seasoning for various traditional dishes, such as stew, roast chicken, or meatballs.

As Lactarius sect. Deliciosi is the most cited WEM in mixtures, we provide a more detailed analysis of their mixtures. It is typically preserved in vinegar (V. vinifera; 22 URs; 3.29%) as an appetizer alone (see the ‘Food uses’ subsection) or mixed with A. sativum, P. nigrum and Laurus nobilis L. As a relevant report, it can be cooked without a vehicle (4 URs; 7.02%), meaning that it is cooked in the oven, grilled or traditionally cooked in hot slate. In all cases, the WEM is seasoned traditionally with ‘all i julivert’ [garlic (A. sativum) and parsley (Petroselinum crispum (Mill.) Fuss)]. In the third case, the slate is rubbed with garlic (A. sativum) beforehand to prevent the stone from breaking apart.

Finally, the informant consensus factor for food mixtures was 0.94. This value is very high, even if it is not yet comparable with other ethnomycological studies, because, to date, scarce attention has been given to fungi in comparison with plants in ethnobiological research. This suggests that its maximum value is one, providing solid information, through the agreement and consistency among informants, of popular knowledge in fungal mixtures with plants and fungi themselves.

Other uses

In this category, non-medicinal and non-food uses were reported. As noted by Gras et al. [11], this category, with its numerous subtypes, is considered fragile, as its traditional functions have diminished over time. Many of the associated tasks have been mechanized, and the once hand-crafted products are now mass-produced and commercially available in supermarkets. Moreover, if ethnomycological studies are overlooked, the category of other uses is even less studied. Nonetheless, these practices and associated knowledge are well regarded by informants because of their cultural relevance and potential to generate income for local communities [11].

In our study, we compiled 21 URs from 15 taxa (Supplementary material). The most reported use in this category was the collection of WEMs for sale, and the taxa cited were Cantharellus cibarius, Chroogomphus spp., Hygrophorus sect. Limacini, Hygrophorus spp., Lactarius sect. Deliciosi, M. oreades, Morchella spp., Ramaria spp., Tricholoma equestre (L.) P. Kumm., T. imbricatum (Fr.) P. Kumm., and T. terreum. Nonetheless, this tradition has largely disappeared.

Lycoperdon perlatum was reported as a game, since children used to play to disseminate its spores, forming a kind of cloud, and A. muscaria was reported as a fly repellent. Sparassis crispa, one of the best-known mushrooms in the area but also the hardest to find, had the sacred tradition of gathering it on the 8th of September (the National Day of Andorra). In addition, in folk literature, there is the expression ‘Si veus una greixa no la facis créixer’, meaning that you must pick the WM if you see it (even if it is small), since, if you do not do so, another may catch it and enjoy its precious taste.

Ethnomycological knowledge and forest management

Traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) is a concept that refers to human interactions with nature in all aspects: cultural, environmental and socioeconomic [85]. It also reflects interactions on a spatial and temporal scale, offering insight into long-term processes in interactions between humans and nature [85]. In this ethnomycological process, other information gathered and reported in the interviews referred to aspects linked to TEK and forest management, such as the seasonality of mushroom picking, morphological identification, ethnographic details, and ecological issues. This ecological understanding is closely linked to forest management practices, as different approaches, such as maintaining open areas, can influence mushroom productivity [86]. However, TEK could not be quantified due to its heterogeneity and the variability in informants’ descriptions.

For example, Boletus sect. Boletus was not known, as per traditional uses, in the territory, and it was between the 1930s and 40 s that French people thought Andorrans that these WMs were edible. With respect to ecological issues, the informants reported that M. oreades has decreased in quantity since fields are no longer working, as an example of changes in agricultural and silvicultural management. As related by some informants prescribed burning is no longer legally allowed and this can modify mushroom availability [86]. Moreover, mushroom picking activities themselves have importantly increased in the late years and there is the perception that inexpert gatherers are performing this leisure activity, which results in populations degradation. These relevant observations and similar reports are also gathered from the findings of Akpaja et al. [87] in Nigeria and Teke et al. [61] in Cameroon, where ecosystem degradation due to farmland expansion, grazing, and settlement growth has contributed to the disappearance of WMs and, consequently, to the loss of ethnomycological knowledge, although in our case, the disappearance of the carpophores of some species is linked with the disappearance of traditional agricultural practices. Many spaces cultivated earlier are no longer used, and the management of some pastures has changed. For example, some meadows or incipient forests are now closed forests, where the mushroom species are different. Given the above, we consider this TEK gathered during the interviews to be highly valuable and insightful for understanding the ethnological context of society and to propose ways to recover some uses.

Between poison and tradition: cultural understandings of mushroom toxicity

Poisonous mushrooms are a significant concern and were reported by 22.14% of the informants. This reflects widespread public awareness of mushroom toxicity, which is also common among healthcare professionals and government authorities, due to the risks associated with foraging, especially among inexperienced individuals. We recorded 61 toxicity reports (TRs) and classified them into three categories: poisonous unless properly prepared (31 TRs; 50.82%), poisonous (25 TRs; 40.98%) and dose-dependent toxicity (five TRs; 8.20%). A total of 11 taxa were reported, five as poisonous mushrooms and six as mushrooms, which should be eaten with precaution to avoid adverse effects. The relevance of knowledge about possible troubles caused by mushrooms is logical in a society that is importantly linked to mushrooms, particularly their culinary uses, to safely select and treat WEMs.

Amanita muscaria, A. pantherina (DC.) Krombh., Lactarius sect. Torminosi (Fr.) Cooke, Ramaria pallida (Schaeff.) Ricken and Tricholoma saponaceum (Fr.) P. Kumm were cited as poisonous mushrooms. Moreover, information about WEMs at risk of confusion with poisonous WMs was also recorded.

Although our informants described A. muscaria as a deadly mushroom, it is not officially classified as such. Its ingestion can lead to euphoria and psychotropic effects, along with brief episodes of central nervous system stimulation and depression [88]. However, severe outcomes can occur, and as informants warn, it should not be confused with Amanita caesarea (Scop.) Pers., especially during the early stages of fruiting body development. Like the first example, A. pantherina can be mistaken for M. procera, which is why the informants avoid consuming the latter WEM. Similarly, there is a risk of confusion between T. saponaceum and T. terreum. Likewise, Lactarius sect. Torminosi is often confused with Lactarius sect. Deliciosi. The former produces white latex and is mildly toxic because of its gastrointestinal irritants, whereas the latter, with reddish latex, is edible. However, according to one informant, eating too many of the edible ones may cause dark-coloured urine as a negative side effect.

Tricholoma equestre is cited as edible with 17 URs; however, some informants mention that it should not be eaten in high quantity since it has adverse effects. Informants also reported that countries such as France prohibited its consumption. This is because acute poisoning has been linked to severe cases of rhabdomyolysis after the repeated consumption of large amounts [89]. Collybia nuda (Bull.) Z.M. He & Zhu L. Yang are also reported as harmful if eaten in abuse; as the locals say, ‘totes les masses piquen’, meaning that all excesses may cause troubles.

Finally, the most cited category, ‘poisonous unless properly prepared’, refers to two taxa: Gyromitra esculenta (23 TRs) and Morchella spp. (8 TRs). These two taxa, traditionally known as ‘murgues’ in Catalan (see the ‘Myconymy and its cultural dimension’ subsection), are considered WEMs. However, previous cooking or preservation methods must be applied to avoid mushroom toxicity. These methods include air drying, boiling with water, or applying both methods before traditional cooking and eating. Notably, informants never eat this WEM alone, always mixed with a source of protein (generally, meat or eggs) and in low quantities. Another taxon named ‘murga’, D. ancilis (one TR), is directly reported as a toxic mushroom. Once this has been established, expressions reported by our informants, such as, translated, ‘Now they say they are toxic. If they were, they would all be dead for years’ or ‘The French say it is deadly, but if it were, there would be half people from Andorra dead’ who are contextualized and applicable to all reported ‘murgues’. However, G. esculenta is the only species reported as toxic and with sale banned in several European countries, such as France or Spain, owing to its consequences, even if preparation or preservation methods are applied. They contain gyromitrin, a toxin that leads to clinical symptoms such as vomiting and diarrhea, followed by jaundice, convulsions, and coma. In addition, both hepatotoxic and carcinogenic effects have been reported in in vivo and in vitro studies [90].

Some informants reported that boiling G. esculenta with a garlic clove (A. sativum) and observing whether the clove turns black can indicate toxicity; others reported that its avoidance by animals or insects serves as a warning sign (as reported in other regions [61]). However, these methods should be understood as cultural beliefs or traditional practices, as there is no scientific evidence supporting their effectiveness in detecting toxicity. Although the consumption of this WEM is strongly discouraged, it has been eaten for a long time and continues to be consumed in traditional and popular contexts.

Myconymy and its cultural dimension

In this research, 155 vernacular names were recorded for 49 taxa (Supplementary material). In the whole CLA (of which Andorra represents less than 1% both in inhabitants and in extension), slightly more than 1,500 vernacular names have been recorded for slightly fewer than 500 taxa [57], so that Andorran ethnomyconymy accounts for approximately 10% of the repertory to name ca. 10% of the taxa. Coprinus comatus (O.F. Müll.) Pers., Sarcodon imbricatus (L.) P. Karst., and Tricholoma portentosum (Fr.) Quél. are the only taxa for which a vernacular name was reported, but no information on use or toxicity was provided. In the case of one taxon, Imleria badia (Fr.) Vizzini, one informant recognized the mushroom as edible in the forest but did not know or could not recall its name.

Out of the 155 vernacular names, four are in French, one is in Basque, and the rest are in Catalan. The most cited taxon in terms of folk name is Lactarius sect. Deliciosi (107 URs; 10.25%), which has been reported 103 times as ‘rovelló’ and four times as ‘rovelló d’avet’; the second name specifically refers to L. salmonicolor, which grows in fir (A. alba) forests (‘avetars’ in Catalan). This ranking is followed by M. oreades with 101 URs (9.67%), 99 of which correspond to the typical folk name ‘carrerola’, one to the close ‘carrereta’ (both linked to the disposition in lines (‘carreres’ in Catalan) of this mushroom [91]) and the third as ‘moixeriga’, associated with the same taxon, as the informant mentioned two folk names for it, the most frequently cited and this one. Figure 4 shows the 20 most cited WEMs and their number of vernacular names associated.

The ethnomyconymy index is 2.45%, a similar value to the ethnomycoticity index (EMI), indicating that most fungi in the territory have not a vernacular name, as they are not used. The linguistic myconymy diversity index has an equivalent in plants, the linguistic phytonymy diversity index, which is usually calculated to value the linguistic richness of a territory independently of its flora [11]. In this case, the linguistic myconymy diversity index achieves a value of 3.16 for all taxa (suggesting a mean of more than three folk names per fungus), with the maximum number of vernacular names given to a taxon being 12 and the minimum being one. These high number and variety of names reinforce the mycophilic character of the territory studied.

Particular attention should be given to taxa with a high number of vernacular names. In general, the existence of a high number of myconyms for a taxon is an indicator of increased knowledge and high cultural relevance of this mushroom in the studied area, as stated for plants by Turner [92] and, as reflected, for the Catalan linguistic area, which concerns the present paper, in the comprehensive work of Cuello-Subirana [93]. Gyromitra esculenta, D. ancilis and Morchella spp. recorded 12 and 10 folk names, respectively, for the first and the other two cases. When analysed in detail, most of them contained the word ‘murga’ alone or with many variants, e.g., ‘murga negra’, ‘murga de cervell’, ‘murga d’orella’, ‘murga de campana’, etc. As reported previously (see the ‘Between poison and tradition’ subsection), these WEMs are considered similar in terms of their properties and poisonous conditions. We believe that this association is based on the similarity of their folk names, and as a precaution, informants prefer to apply all the methods described. Finally, Lactarius sect. Torminosi, an ethnotaxon composed of poisonous wild mushrooms, was associated with nine folk names. We believe that this high number of names reflects the particular attention given by the informants regarding toxic mushrooms in the territory studied, since few vernacular names are reported concerning poisonous mushrooms [68]. Few poisonous species have specific vernacular names; informants typically just recognize that they are ‘not good’ and avoid them. However, in the case of Lactarius sect. Torminosi, its resemblance to the well-known and widely consumed Lactarius sect. Deliciosi may explain the abundance of folk names used to refer to it. Since this high myconymic variability also occurs in Andorra for other taxa, we believe that people who collect and/or eat mushrooms should be very concerned with the possibly toxic ones and talk often about them (even if just to remind them that they are toxic or to fix particular details for a correct identification), so diverse names and variants are not rare.