The 30th Conference of the Parties (COP) — the annual meeting of countries that signed the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) — is currently underway in Brazil.

PREMIUM Indigenous activists participate in a protest at the COP30 U.N. Climate Summit, Friday, Nov. 21, 2025, in Belem, Brazil. (AP Photo/Andre Penner)(AP)

PREMIUM Indigenous activists participate in a protest at the COP30 U.N. Climate Summit, Friday, Nov. 21, 2025, in Belem, Brazil. (AP Photo/Andre Penner)(AP)

As with every COP, COP30 will review how far nations have come in meeting past commitments to avert or adapt to the climate crisis, and may set new ones.

This moment offers an opportunity to assess whether the 29 COPs held since 1995 have made any real difference. Here is what the data shows.

The ultimate reason for the COP negotiations is global warming. Assessed on this metric alone, the talks so far do not indicate success. The world has already recorded one year of 1.5°C warming, suggesting that a long-term breach of this threshold is no longer far off. Global leaders agreed in the 2015 Paris Agreement to limit warming to 1.5°C, as exceeding it in the long term could trigger irreversible changes in the climate.

The reason global warming has reached this point is that human beings continue to add greenhouse gases to the atmosphere. An increase in these gases means that the energy reaching the Earth from the sun gets trapped for longer, instead of being radiated back into space — a process HT has described in detail here.

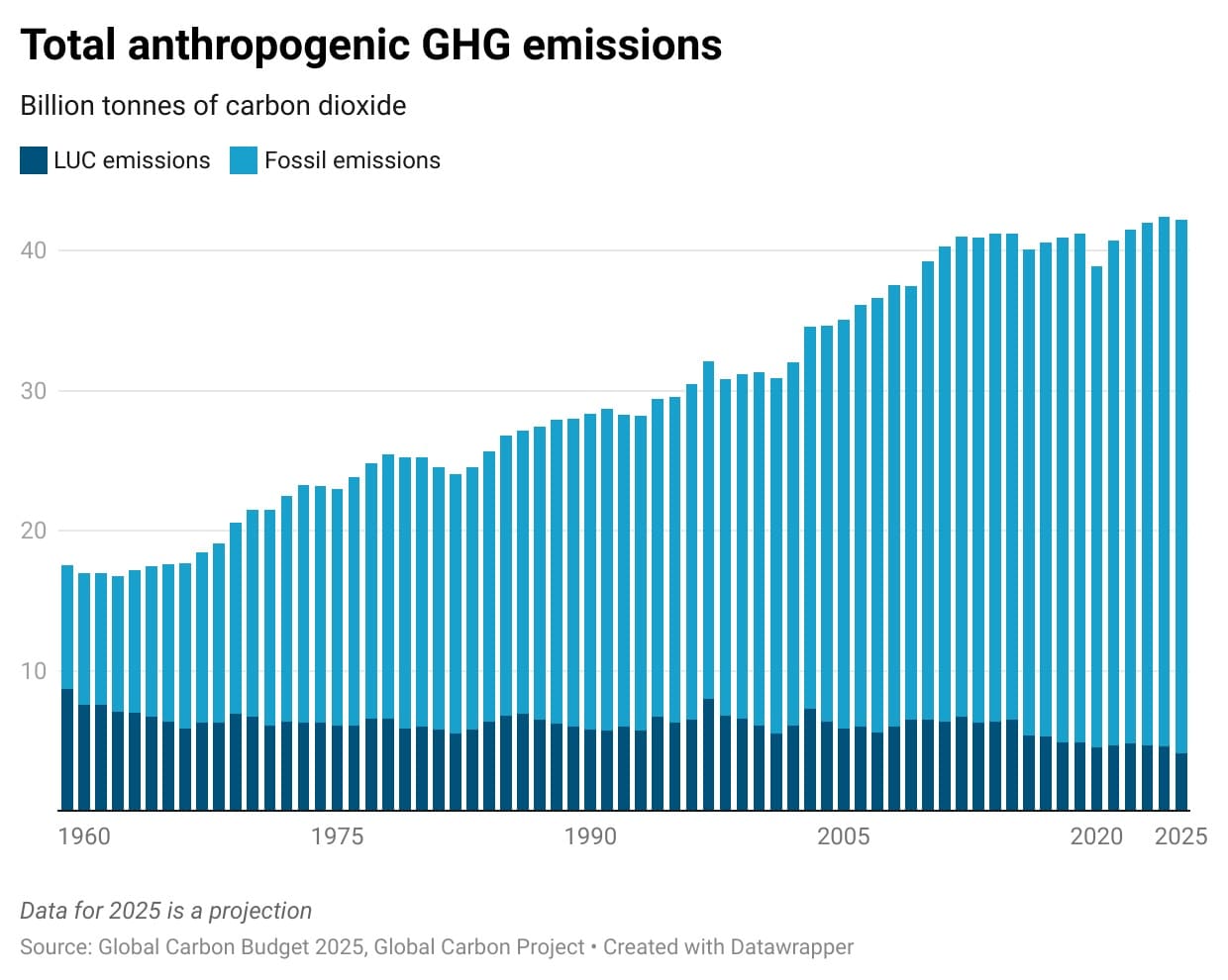

A paper published on November 13 by the Global Carbon Project (GCP), a global consortium of scientists, shows that GHG emissions from fossil fuel use (after accounting for the carbon dioxide absorbed by cement) hit a record high in 2024, equivalent to 37.8 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide (GtCO₂). In 2025, emissions are projected to rise further to 38.1 GtCO₂.

To be sure, burning fossil fuels is not the only way humans add greenhouse gases to the atmosphere. Changes in land use — such as converting forests to farms or concretised areas — also contribute, because trees absorb carbon dioxide. This Land Use Change (LUC) component added another 4.6 GtCO₂ of emissions in 2024, down from 4.7 GtCO₂ in 2023. It is projected to decline further to 4.1 GtCO₂ in 2025. This means total human GHG emissions reached a record 42.4 GtCO₂ in 2024 but are expected to fall slightly to 42.2 GtCO₂ in 2025.

Does this projected net decline in anthropogenic emissions in 2025 signal any impact of COP negotiations so far? Not really. There are at least two reasons for this. First, the GCP paper itself notes low confidence in the LUC projection because it is based on proxy estimates. Second, the decline shown by these estimates is largely due to reduced forest loss from fires in South America — a change likely linked to the easing of El Niño conditions, a cyclical warming of the equatorial Pacific that adds to global temperatures. With El Niño absent in 2025, global temperatures have come off their 2024 peak only temporarily, and the reduction in fires may simply reflect this short-term shift. In other words, the slight expected decline in total human emissions is neither new nor the result of structural change.

Total anthropogenic GHG emissions

Total anthropogenic GHG emissions

However, this does not mean climate negotiations so far have been a complete failure. LUC emissions, for instance, have been stagnant for some time and are declining over the long term. Similarly, while fossil fuel emissions continue to rise, the pace of growth has slowed. As expected, the growth rate of total human emissions has also decelerated. Without even this limited progress, the world might already have crossed the 1.5°C threshold in the long term.

(Abhishek Jha, HT’s senior data journalist, analyses one big weather trend in the context of the ongoing climate crisis every week, using weather data from ground and satellite observations spanning decades)

All Access.

One Subscription.

Get 360° coverage—from daily headlines

to 100 year archives.

E-Paper

Full Archives

Full Access to

HT App & Website

Games

Subscribe Now Already subscribed? Login