America’s last nuclear detonation was nothing special. Smaller than the bomb that killed 73,000 people in Nagasaki, it exploded 1,397 feet below the Nevada desert. It shook the ground, created a shallow concavity in the sand, and killed no one that we know of, although it vented 0.1 curie of radiation, an amount used in nuclear medicine to kill thyroid cancer.

Called “Divider” by the Los Alamos National Laboratory, the test reportedly, unofficially, measured the ability of the W91 warhead mounted on an air-to-ground missile to withstand shocks and fire after being dropped by a B-52. The results are classified.

But Divider marked the end of the Cold War. Nine days after the test, on Oct. 2, 1992, President George H.W. Bush bowed to congressional and popular pressure and signed a nine-month pause in underground nuclear testing. A series of scheduled tests at Nevada was canceled, and both the missile and W91 warhead were dropped.

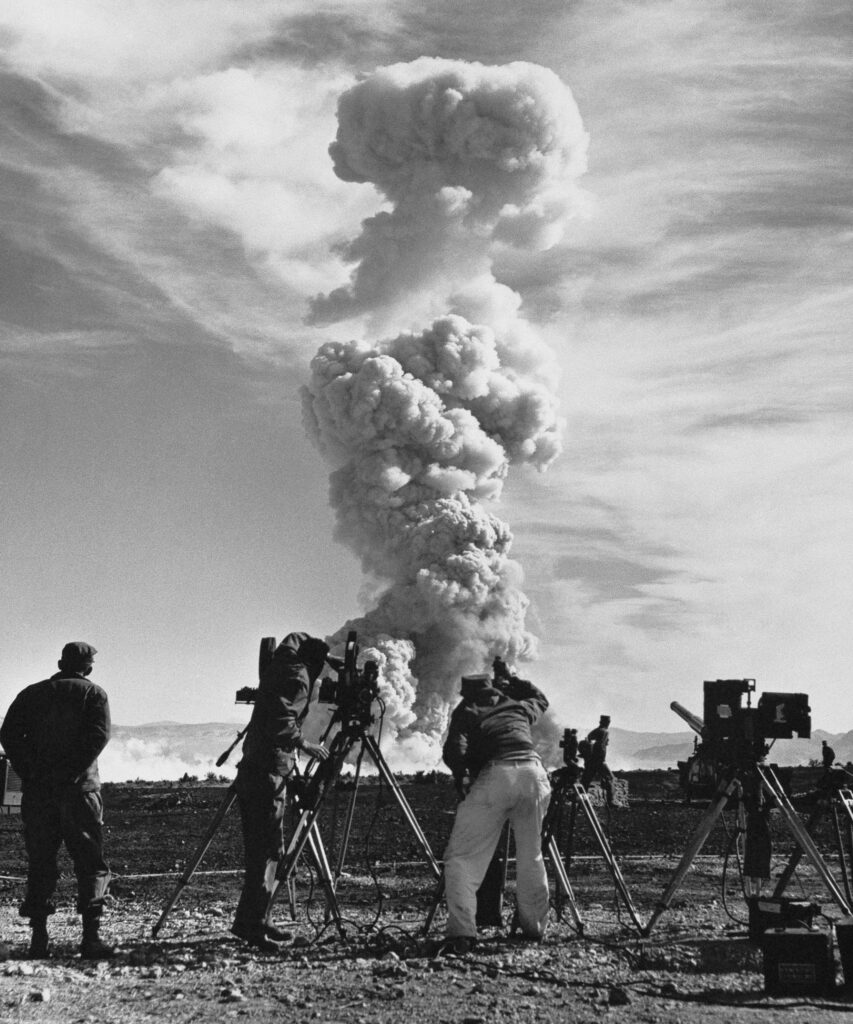

In this June 1953, photo, film crews photograph an atom cloud forming after an atomic shell fired a test in the Nevada desert. (The Associated Press file)

In this June 1953, photo, film crews photograph an atom cloud forming after an atomic shell fired a test in the Nevada desert. (The Associated Press file)

After 47 years, and 1,054 tests, the United States stopped blowing up nuclear bombs. Nevada had hosted 928 of those tests — 100 of them in the open air, which spread radioactive fallout across the country, most heavily in neighboring Utah. Another 106 tests contaminated Pacific Islands. Seventeen tests were conducted in the continental U.S. at Meeker and Parachute, Colo.; Carlsbad and Alamogordo, N.M.; in Alaska, Nevada and Mississippi.

Until they went underground at the Nevada Test Site, nuclear tests were a tourist attraction in Las Vegas, where cocktails were served on casino rooftops in full view of mushroom clouds 65 miles away. Photos and films showing whiplashed trees, flying house parts, squealing pigs, bleachers full of sunglass-wearing VIPs, and Army troops marching toward an eruption remain as artifacts of America’s braggadocio of its nuclear might. Even today, tours are available to show bent bridges, huge craters and towers erected for tests that were canceled.

On July 3, 1993, President Bill Clinton began to negotiate a global test ban treaty. Adopted in 1996 and signed by 186 countries — though no nuclear power, including the United States, ratified it — the treaty made nuclear testing taboo, in the judgment of the Arms Control Association.

Less than a year into Clinton’s first term China tested a nuclear bomb and Clinton responded with a secret memo, signed Nov. 3, 1993, called “Presidential Decision Directive 15.” It stipulated that the United States must maintain a capability to resume testing and “a capability to conduct a nuclear test within two to three years.” President Joe Biden affirmed the policy in 2022 with National Security Memorandum-7, which “establishes as U.S. policy an expectation that the United States must be ready to perform an underground nuclear explosive test using a (weapon) drawn from the existing stockpile and limited diagnostics within 36 months, assuming current barriers to achieving this timeline in relevant laws and regulations will be overcome.”

Under this policy, President Donald Trump has the authority to order a resumption of nuclear testing, as he did on Oct. 29. His order, delivered as Air Force One was about to land in South Korea to meet with Chinese President Xi Jinping, brought stunned silence from officials responsible for America’s nuclear weapons. According to CNN, a delegation that includes Energy Secretary Chris Wright, National Nuclear Security Administration leader Brandon M. Williams, and officials from the U.S. National Laboratories will visit the White House in the coming days “to dissuade” Trump from testing.

What they will tell the president, presumably, is that testing is not necessary to maintain America’s nuclear dominance, and that it could ignite both a global arms race and noisy anti-nuclear opposition not seen since the 1980s.

“If there is a threat of resumed testing today, it most likely comes from a desire for political posturing rather than technical necessity,” wrote Dylan Spaulding, a physicist with the Union of Concerned Scientists.

If testing were to resume, the Nevada Test Site is the only underground site designated for nuclear weapons testing.

The White House has said testing is necessary to keep pace with testing by Russia and China.

When asked on 60 Minutes why he needed the test, Trump replied, “Well, because you have to see how they work. You know, you do have to. And the reason I’m saying testing is because Russia announced that they were going to be doing a test. If you notice, North Korea’s testing constantly. Other countries are testing. We’re the only country that doesn’t test … I don’t want to be the only country that doesn’t test.”

He insisted that Russia and China are both testing, though “they don’t talk about it.”

Supporters of testing pointed to several reasons to conduct them, some of them technical and other political, including demonstrating the country’s nuclear capability and ensuring the reliability of the stockpile.

Writing for the Heritage Foundation, Robert Peters, a senior fellow at the group’s Allison Center for National Security, said while it might be technically correct that there’s no need to test the current arsenal, the U.S. is building new warheads.

“It may, in fact, be necessary to test these new systems to ensure that they work as designed. Modelling and simulation may be sufficient to assess the viability and characteristics of these new warheads — but that is not a proven proposition,” he wrote.

“Moreover, the purpose of nuclear weapons is to deter one’s adversaries from carrying out breathtaking acts of aggression. In that sense, even if nuclear explosive testing is not necessary to convince American policymakers that next-generation nuclear systems work, it may be necessary to convince America’s adversaries that its nuclear arsenal is credible,” he said, adding a test might also be necessary to “demonstrate resolve.”

The Preparatory Commission for the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty Organization (CTBTO), which monitors nuclear testing through its International Monitoring System, reports that North Korea is the only country to have exploded nuclear weapons in recent years, producing underground blasts that were picked up by seismic monitoring stations. Daryl Kimball, executive director of the Arms Control Association nonprofit, said in an online statement that “no country, except North Korea, has conducted a nuclear test explosion in this century, and even they have stopped.”

“Accusations that Russia and China may have conducted very low-yield but super-critical nuclear weapons tests are unsubstantiated and highly debatable, and such tests provide little value for advancing the capabilities of their nuclear programs. Such concerns are far better dealt with by ratifying the CTBTO and securing the option for short-notice on-site inspections and/or other forms of confidence-building measures,” Kimball said.

Under the innocuous sounding “stockpile stewardship,” the United States has made enormous scientific and technical leaps in supercomputing and equipment, to the point that under the Nevada desert the alchemy of thermonuclear bombs is being divined and tested without creating a critical mass that explodes.

A canister containing the Divider test device is shown during the last nuclear test at Nevada, Sept 23, 1992. It was lowered into a deep shaft, which was backfilled, and exploded. (National Archives)

A canister containing the Divider test device is shown during the last nuclear test at Nevada, Sept 23, 1992. It was lowered into a deep shaft, which was backfilled, and exploded. (National Archives)

So confident are scientists and engineers in the process that they certify annually in a letter to the president that nuclear weapons in the stockpile will explode as designed. A similar letter from the commander of U.S. Strategic Command states that its weapons work and that tests are not needed. This assurance process, begun by Clinton, is in its 30th year. Until Trump’s surprise announcement, leaders of the U.S. nuclear enterprise insisted repeatedly that exploding nuclear devices to test them is unnecessary.

Stockpile stewardship, in essence, involves miniature replication of the process invented by J. Robert Oppenheimer’s team at Los Alamos in 1945 that creates a critical mass of plutonium by an imploding sphere. The first bomb, Trinity, and the bomb dropped on Nagasaki, were plutonium implosion bombs. In subsequent bombs, called hydrogen or thermonuclear bombs, the plutonium explosion triggered fusion contained in a small tank of tritium gas.

Today, the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California uses lasers in its National Ignition Facility in a quest for fusion, the perpetual power of the sun. The lab’s day job, though, is bombarding BB-sized capsules filled with deuterium and tritium to mimic what happens in a plutonium implosion bomb, the “primary” for H-bombs, according to Spaulding. A “primary” serves as the trigger for the much larger fusion reaction

“You’re studying how deuterium and tritium fuse, and how you generate a spherical implosion, and the kinds of physical instabilities. When you try to squeeze those fusion capsules, the analogy is, it’s like squeezing a water balloon between your hands, right? You don’t want it to bulge out anywhere. It’s really hard to do that symmetrically. There’s all kinds of little ripples and things that form. And the same thing is true of the inside of a primary.”

The ignition facility “can also generate very high X-rays and other forms of radiation that they can use to do weapons-effects testing. So if you want to know, for instance, what happens to your bomb if it’s exposed to a nuclear detonation nearby or even in space, you can put your components in the NIF target chamber or nearby, expose them to radiation from the experiments and see whether your electronics get fried.”

Los Alamos personnel, meanwhile, are installing a huge, permanent, $2 billion complex called PULSE, which stands for Principal Underground Laboratory for Subcritical Experimentation. Dug 1,000 feet below the desert, a maze of tunnels 2 miles long connect to a control room.

One of its tasks is to study the quality of bombs in the stockpile. The PULSE machinery can bombard microscopic bits of plutonium with neutrons or electrons and yield high-speed X-ray images of the metal, without blowing it up. With that 400-foot machine, they can compare the performance of aging plutonium pits with newly forged ones made at Los Alamos and what their supercomputer simulations say they should be, said Spaulding.

A second set of tests are aimed at understanding “what are called performance margins in a weapon,” Spaulding said. “What I’m sensing and getting from conversations with the NNSA is that margins are really where their uncertainties are. It’s not that they’re worried that new warheads won’t work. … The game is really understanding if there’s a 10% uncertainty in one factor in the experiment: How does that propagate to an uncertainty in yield in a weapon that is, say, 60 or 70 years old.”

Some tests planned for PULSE are done in large containment spheres that reduce the risk of radioactivity escaping. Ignited in alcoves, the spheres are then sealed away with cement walls.

America’s nuclear testing technology has evolved dramatically since Divider. Today, each test costs millions of dollars and ends with the bomb and its equipment vaporized and entombed thousands of feet below ground. Of the 800 underground tests at the Nevada Test Site, 32 leaked radioactive iodine.

Meanwhile, Russian President Vladimir Putin told his ministers to propose “reciprocal measures” if the United States tests.

Ultimately, the U.S. investment in nuclear technology is a psychological deterrent that may be as powerful as a new warhead, nuclear experts say, and that the work of supercomputers and billion-dollar equipment that mimic nuclear processes projects a technical sophistication as powerful as the number of warheads.