Christmas is a time filled with memories for mum-of-two Azra Omerbegovic – some happy, but many too painful to revisit.

Tomorrow, it will be 30 years since the signing in Paris of the Dayton Peace Agreement, marking the end of the Bosnian War, but the horror of the conflict remains for many victims.

Now living in Birmingham with her husband Refik – Azra, 47, was born in Sarajevo, a city then based in Communist Yugoslavia, where she lived happily with her parents and two brothers, one older and one younger, until April 5 1992 when their lives changed forever.

At the start of the decade, Communism collapsed across Eastern Europe, leading to the break-up of Yugoslavia, as various republics declared independence.

Sarajevo was in the newly formed Bosnia and Herzegovina, which declared independence on March 1 1992, with a population of 44% Muslim Bosniaks, 32.5% Orthodox Serbs and 17% Catholic Croats. The Muslims became pariahs, resulting in mass bloodshed. And Sarajevo endured the longest siege in the history of modern warfare – lasting three years, 10 months and three weeks – from April 5 1992 to February 29 1996. Led by Bosnian Serb forces commanded by General Ratko Mladic, the aim was to ethnically cleanse the Muslim Bosniaks.

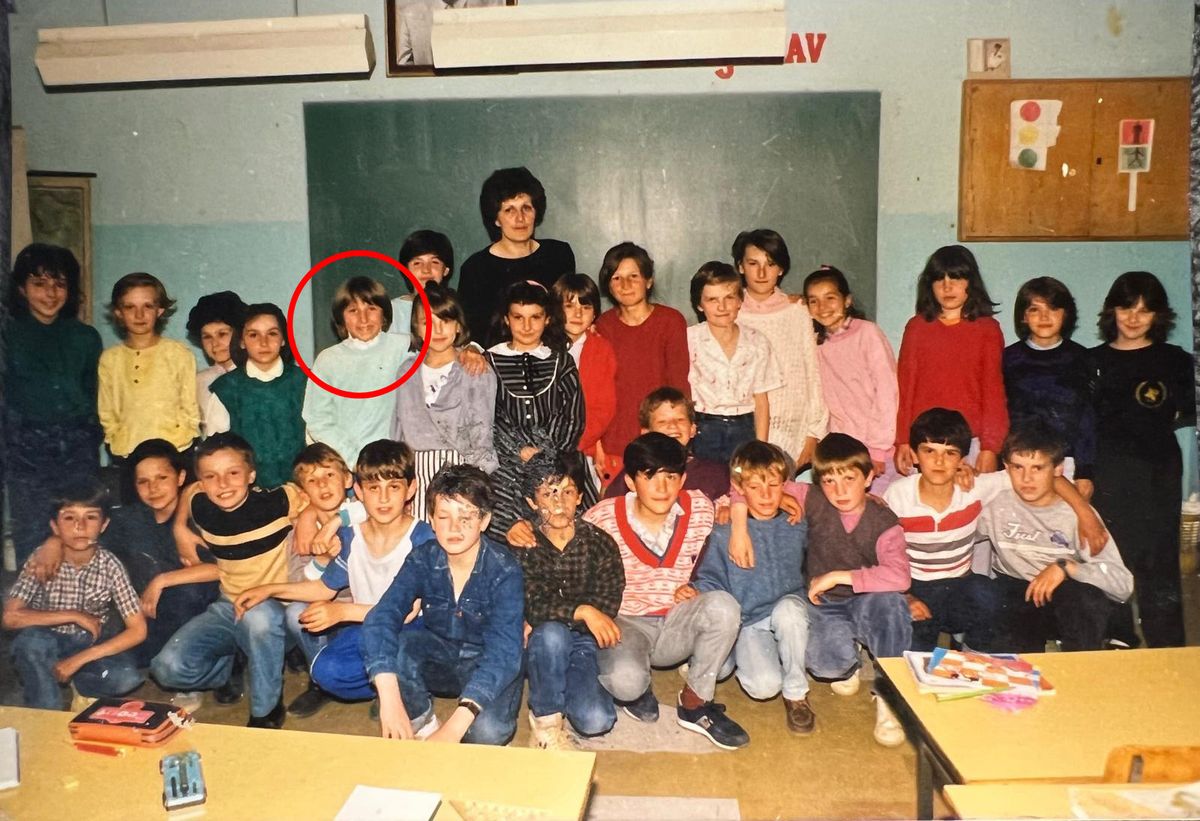

For Azra there was no logic to the warfare. She had been blissfully happy in her mixed secondary school, with friends of all faiths. Recalling the change after independence, she says: “At school, we [Bosniaks] were suddenly discriminated against just because of our names. I remember one Serb classmate saying, ‘We are going to kill you all’, and the teacher, also a Serb, said to him, ‘George, stop making jokes’. We all laughed and brushed it aside. That was Friday. The following Monday, we didn’t go to school.”

In April 1992, her Serb neighbours left Sarajevo – including her best friend Jelena. The Bosniaks who remained were under siege. “They meant for Serbs to move out of the city, leaving it as a clear shooting range,” says Azra. “The bombing started, snipers were shooting from every direction, shells were raining from the hills. People were dying, children were being killed.”

They lived without water, electricity and food for most of the siege, by the end of which 12,000 people – among them 1,600 children – were dead.

Women and girls were gang-raped and civilians were tortured, starved and murdered. Many were driven into concentration camps, including Azra’s father-in-law, who spent seven months in two camps near Vlasenica and Batkovic. She says: “The camps were extremely overcrowded, with no basic facilities for washing, toilets or food. Beatings and executions were a daily routine. He still has nightmares and feels the side effects of torture.

“We experienced fear like no one could imagine. Hunger, the thirst, the cold and the darkest days that stayed for 1,425 days. I didn’t have time to be a teenager. I grew up overnight. I had to help my mum find food and water while she looked after my younger brother who was only five. Many nights we would spend in the crowded, dark, damp basement, not knowing when or where we would get our next meal from. Thankfully, we received parcels from Islamic Relief, I don’t know what we would have done without them.

“I remember when Mladic, who led the Army of Republika Srpska, said, ‘Shell Velušici and Pofalici [neighbourhoods] because there are no Serbs living there. Don’t let them sleep at all. Make them go insane’. That night we left our home running without shoes toward the shelter, shivering and crying out of fear. I thought we were not going to make it through the night.” One day she received news her 90-year-old grandmother had been burnt alive by a Serb soldier who pushed her into a fire.

Azra says: “Day and night, we were listening to the radio, hearing the news from all parts of Bosnia. Rape, killing and destruction became the norm. Srebrenica was besieged too, despite being a UN safe zone. Even after the promise of ‘never again’, after the Holocaust, genocide happened again in Srebrenica in July 1995. The whole world watched in silence.”

On July 11 1995, Bosnian Serb soldiers captured Srebrenica in eastern Bosnia and Herzegovina and killed more than 8,000 Bosniak Muslim men and boys, in the largest massacre seen on European soil since the Second World War. Reflecting on her reaction to the Dayton Peace Agreement, Azra says: “We welcomed it with disbelief, but a glimmer of hope emerged we’d be able to survive the winter. The war stopped but not a single family did not lose a close member.”

In 2005, she visited the UK as part of a university programme, meeting her future husband Refik, pictured with her right, an IT analyst working for the NHS. Azra is taking a two-year absence of leave from her PhD in philosophy and religion, at Birmingham University.

Living a settled family life once again, she remains a proud Bosnian Muslim and will never forget how loved ones suffered. She says: “I share my story in the hope we learn from the past, and act today to challenge racism, hatred or any form of discrimination, so any violence driven by ignorance or prejudice never happens again.”

Shahin Ashraf, head of global advocacy for Islamic Relief, says: “What we saw happen 30 years ago in Srebrenica was one of the worst crimes against humanity. It all began with seeing others as subhuman.”

Islamic Relief is marking the anniversary with survivors’ testimonies and images from award-winning photojournalist Alix Fazzina. See more here.