“We interviewed people in their 70s, 80s, and 90s who had never lived in Norway, yet spoke fluent Norwegian,” says language researcher Alexander Lykke from OsloMet.

He has been to the USA twice to document what remains of the Norwegian language.

The Americans spoke the old rural dialect from the Norwegian villages their parents or grandparents came from.

Lykke and the Norwegian research team travelled through Minnesota and Wisconsin, where large numbers of Norwegians settled from 1850 onwards.

In Westby, Wisconsin, for example, confirmation classes were taught in Norwegian all the way into the 1940s, until a pastor arrived who did not speak the language.

“They spoke the Gudbrandsdal dialect with the same grammar and old word forms,” says Lykke.

Tight-knit Norwegian communities and continued immigration helped preserve the Norwegian language for a long time.

“US law required schools to teach only in English, but nobody enforced it. So Norwegians taught in Norwegian. Poles taught in Polish, and Germans in German,” says Joe Salmons.

He is a professor of linguistics at the University of Wisconsin and researches immigrant languages.

Swedes switched to Norwegian

Norwegian immigrants met, worked with, and lived nearby people from other countries.

Salmons explains that a lesser-known part of language development in the USA is that both immigrants and Americans learned languages other than English. Especially children.

“Many Anglo-Americans became very

proficient speakers of all sorts of different immigrant languages. If all the kids on the

playground spoke Finnish, so you learn it to talk

to the other kids ,” says Salmons.

He describes an area in Wisconsin with a large Norwegian immigrant community and much fewer Swedes.

“The Swedes eventually switched to Norwegian,” says Salmons.

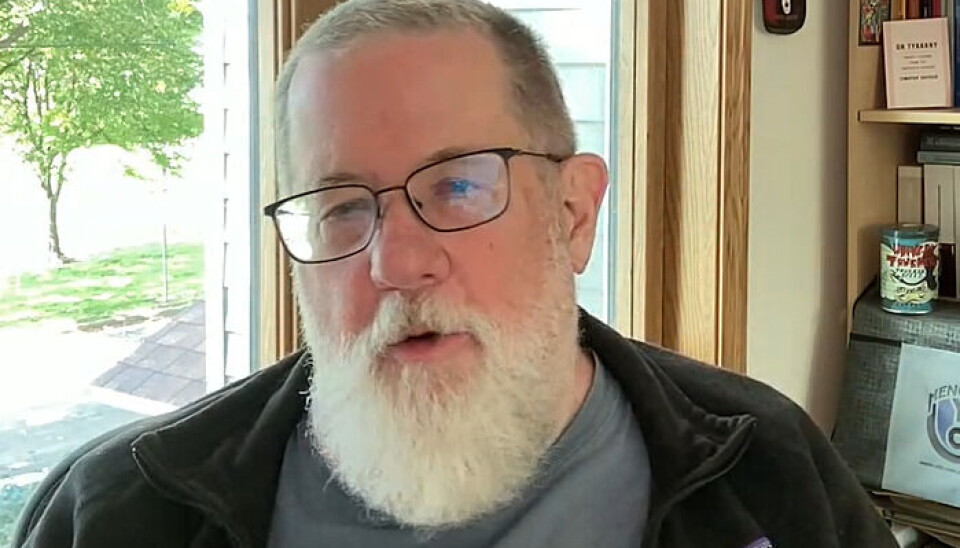

Joe Salmons is a professor of linguistics at the University of Wisconsin. He is very familiar with research on Norwegian in the USA and collaborates with Norwegian researchers. Much is similar for German, which is his language.

(Photo: Nina Kristiansen)

Had to leave to find work

The Norwegian immigrants held onto the language from their homeland for a long time, but then American society changed.

“Family farming started to fade. People left their local communities to work in factories. The schools started teaching in English,” Salmons explains.

“But the kids continued to speak Norwegian during breaks,” says Lykke.

Religion had kept the mother tongues alive. In Norwegian churches, it was considered ideal to use Norwegian in services.

“Norwegian was considered the language of the heart. But then the Lutheran churches merged, and English became the common language,” says Lykke.

Americans first and foremost

At the same time as Norwegian-Americans left their local communities to pray, work, and get an education, strong patriotic movements emerged in the United States.

During World War I, it became especially important that everyone in the US should see themselves as Americans first.

This accelerated integration.

But even though immigrants were pushed to Americanise, Norwegian traditions, food, and language did not disappear.

“There’s a widespread belief in the US that European immigrants integrated very quickly, but that’s nonsense. It’s a myth that is being misused politically,” says Lykke.

Language disappears in three generations

Mike Putnam is a professor of German and linguistics at Penn State University.

He refers to a well-known theory in linguistics: That an immigrant language typically disappears within three generations.

Mike Putnam researches German in the United States, including the old-fashioned language of the Amish people, who do not mix with the rest of society.

(Photo: Nina Kristiansen)

The first generation are of the immigrants themselves. They speak their native language at home, but outside they encounter the language of their new country.

The second generation is their children. They hear the heritage language at home and may learn to speak it, but parents want their children to thrive in the new society. Some parents choose to speak English themselves, others will flip back and forth.

The third generation is the grandchildren. They have no exposure to the heritage language and are unable to communicate with their grandparents.

“When that happens, grandparents often have a kind of allergic reaction to the loss of their heritage, and will try to reignite interest in their language and culture,” says Putnam.

Spoke the Trønder dialect with her grandfather

This happened to Evelyn Galstad. Her grandfather was eight years old when he came to the United States. All his life he spoke the Trønder dialect at home, but he never passed the language on to his children.

“As he got older, he regretted not holding on

closer to the ties that he had in Norway and his family that were left there. I think it was just

sort of a moment that it clicked that I was the last one that he could teach Norwegian,” says Galstad, who is the youngest of the grandchildren.

She speaks the old Trønder dialect fluently, although she switches to Bokmål when she teaches Norwegian at Luther College in Iowa.

“But I couldn’t read or write Norwegian until much later,” says Galstad.

Evelyn Galstad is the youngest of eight grandchildren – and the only one her grandfather taught Norwegian.

(Photo: Anders Moen Kaste)

“Understood Norwegian worse than they spoke it”

100 years after Americanisation fully took hold, Alexander Lykke sat in churches making recordings of elderly people who still spoke their heritage language. This is what researchers call languages children learn at home but which are not the main language of the wider society.

Many of those he interviewed did not learn English until they started school. Some still spoke with a noticeable Norwegian accent.

By then, most were comfortable speaking English and mixed English words into their Norwegian.

“They sometimes struggled to find the right words, but they were clearly speaking Norwegian in distinct dialects. In fact, they understood Norwegian less than they spoke it. Several had trouble understanding the Oslo dialect. They still spoke the dialect of their mother or grandfather,” says Lykke.

He conducted fieldwork in 2016 and 2022. Much had changed.

“Many had passed away, and those who remained were six years older. They found it harder to bring out their Norwegian,” says Lykke.

Relevant to all immigrant languages

How people age with a heritage language is something that interests researchers.

Lykke tells the story of a grandmother whose native language was Norwegian and who later developed dementia. As her condition worsened, she began to lose her English. Her grandchild had to learn Norwegian in order to communicate with her.

For that reason, research on Norwegian in the United States is now about more than documenting old dialects or studying what happens to Norwegian in an English-speaking environment.

“This is valuable knowledge for all immigrant societies and for everyone who moves to other countries. We can learn about different forms of multilingualism, how languages change, and what language means for social life and personal identity. Most importantly, we learn what happens to immigrants’ languages as they age and experience cognitive decline,” says Lykke, adding:

“This is also useful for understanding Somali and Polish immigrants in Norway.”

———

Translated by Alette Bjordal Gjellesvik