The Hastrup find, with more than 200 bronze fragments, reveals commercial and cultural links between Denmark and the heart of Europe 2,700 years ago.

In June 2019, Gheorghe Popescu, a metal detectorist, made an extraordinary discovery in a forest in Hastrup, on the Jutland Peninsula, Denmark. What he found was not a handful of loose coins, but more than 200 fragments of bronze objects, a treasure that has turned out to be a unique window into a period of major change and long-distance connections in prehistoric Europe.

A comprehensive study published in the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports now reveals the secrets of this find, showing that these objects, made between 2,800 and 2,600 years ago, traveled more than a thousand kilometers from the Alps to northern Europe.

To understand the importance of the Hastrup treasure, one must place it within the European scene between the 8th and 6th centuries BC. In southern Scandinavia, it was the twilight of the Nordic Bronze Age. At the same time, in Central Europe, the Hallstatt culture was flourishing, known for its warrior elites and rich burials.

This was a time of reconfiguration. The trade networks that for centuries had carried bronze (an alloy of copper and tin) from the Alpine mines northward were beginning to change. The climate was cooling, agricultural practices were shifting, and iron was beginning to emerge as the metal of the future.

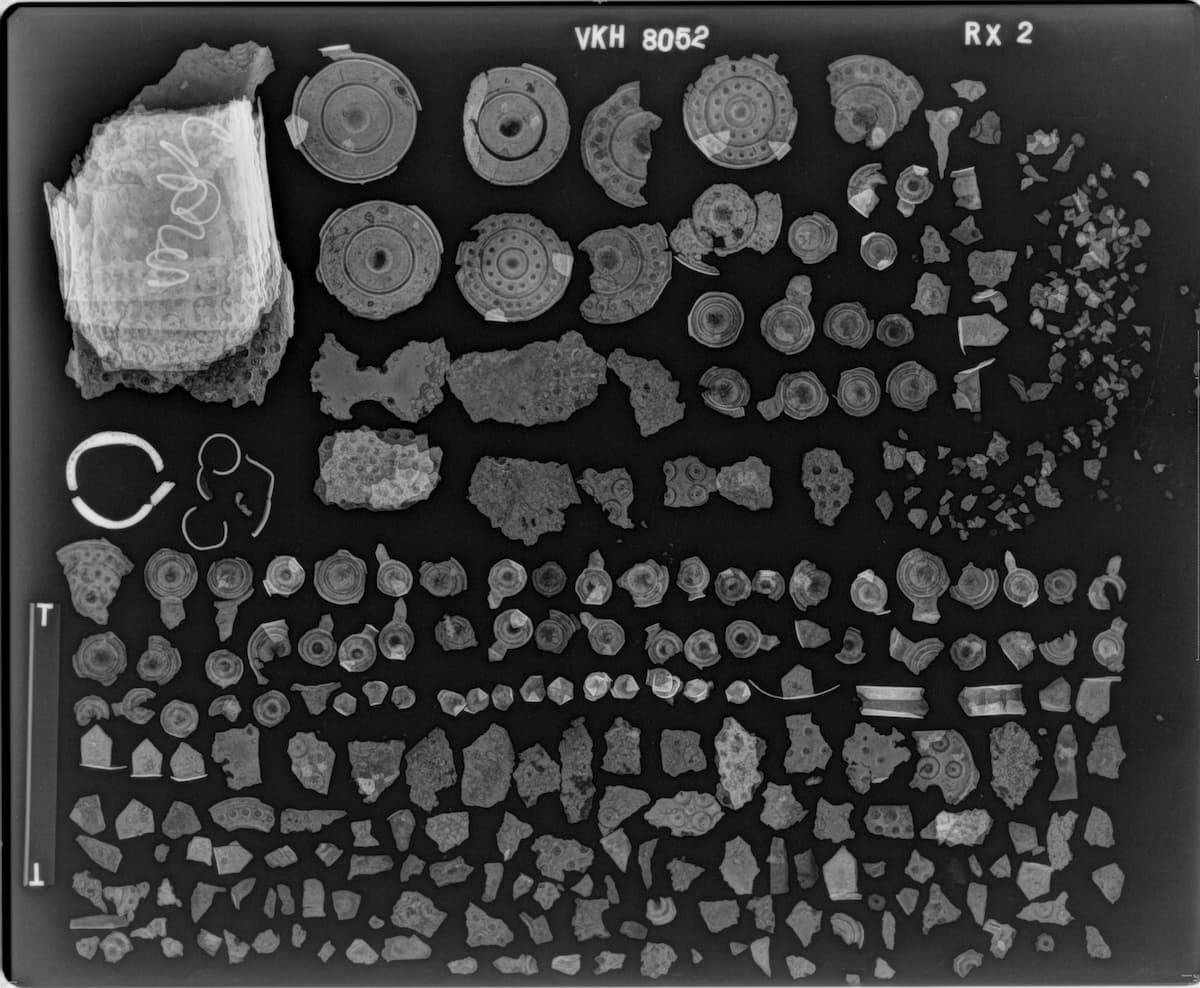

X-ray image of the Hastrup hoard (all objects are bronze artefacts). Credit: Konserveringscenter Vejle

X-ray image of the Hastrup hoard (all objects are bronze artefacts). Credit: Konserveringscenter Vejle

It was a time marked by major cultural and economic transformations, during which pan-European networks of connectivity and trade experienced multiple disruptions, the study notes. In this context, the deposition of valuable objects, known as a “treasure,” was not a simple hiding place, but probably a ritual offering, a way of marking status or of interacting with the divine.

The find: more than 200 pieces of a puzzle

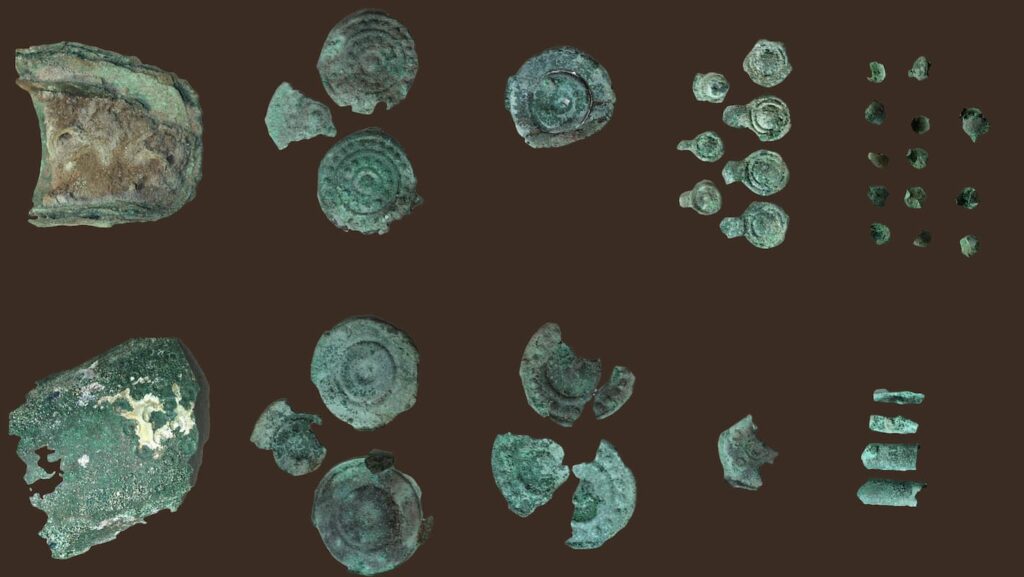

The treasure, carefully excavated by the Vejle Museum, consists exclusively of fragments. Researchers have managed to classify them into eight groups, all made of fine sheet metal and decorated using repoussé techniques. The most striking are a series of discs or circular plates of different sizes.

Large Discs: A minimum of eleven plates, between 36 and 46 mm in diameter, decorated with concentric motifs of dots and circles. Their most distinctive feature, which makes them unique, is four “clips” or clamps on their reverse, a fastening detail without known parallels in northern Europe.

Small Discs: Between 64 and 70 smaller plates, with two clips on the back, also decorated.

Receive our news and articles in your email for free. You can also support us with a monthly subscription and receive exclusive content.

Sheet Plates: Fragments of thin bronze sheets decorated with concentric circles, possibly parts of belts or the decoration of a wooden cart.

Other elements: The treasure also includes thick and thin rings, bronze tubes, and small buttons or studs, the latter very common in the Hallstatt culture.

What were all these objects? The researchers point to a use linked to female ceremonial attire or to the equipment of horses and ceremonial carts. The coherence in the typological expression of the artifacts (…) supports the interpretation that the treasure comprises items that once formed part of the same garment or equipment, the article concludes. The Nordic context reinforces this idea, as ritual deposits with objects associated with women and processional carts are abundant in this region.

A foreign style in Nordic lands

Here lies the first major revelation of the Hastrup treasure: its style is not local. None of these types of objects, especially the discs with clips, have close equivalents in the Nordic Bronze Age. However, their stylistic affinities connect them directly with the art and craftsmanship of the Hallstatt culture in Central Europe, particularly with its final phase (HaD).

The closest parallels are found at sites in southern Germany, northern Italy, and eastern France. The study includes comparative images of nearly identical pieces found in Obertraubling (Bavaria) and in the necropolis of Este (Italy). Bronze ornaments, in small and large versions, dominate the find, but the Hastrup discs with the four clips on the back have no parallel in the Nordic region to date, the research states. This uniqueness raises an intriguing question: were they imported as such, or were they made locally, imitating a foreign style with a distinctive innovation of their own (the clips)?

To answer how these objects reached Denmark, the scientific team, led by Louise Felding, Daniel Berger, and Heide Wrobel Nørgaard, carried out a sophisticated archaeometallurgical analysis. They selected eight representative fragments and subjected them to tests to determine their chemical composition and the isotopic “fingerprint” of their metals. The results form a complex map of sources and trading practices.

The copper used came from at least three or four different mining regions, all located within the vast Alpine area. Lead isotope analyses point to areas such as the Schwarz-Brixlegg district (in the northern Alps, between Austria and Germany), the Slovak Ore Mountains, and, notably, to the southern Alps, in the Trentino region (Italy).

The chemistry of the metal reveals a crucial practice of the time: mixing and recycling. Some objects, such as a thick ring and a small disc, show a perfect chemical correlation. This indicates that they were made by melting together two different metal batches: one of tin-poor copper derived from fahlerz ores (typical of the central Alps or Slovakia), and another of bronze (copper with tin) made with copper from southern Alpine chalcopyrite, possibly from the Calceranica mine in Trentino.

By contrast, two of the large discs and the decorated sheet plates were made from a single batch of very pure metal, with a likely origin in the southern Alps. This suggests that these pieces were made together, in the same workshop and for the same purpose.

The origin of the tin, an essential metal for making bronze, is more difficult to pinpoint. The isotopic signatures of tin in the Hastrup objects are compatible with several regions, but the most likely, given the evidence for prehistoric mining, are the deposits of Cornwall (in southwestern Great Britain) and the Ore Mountains (Erzgebirge, between Germany and the Czech Republic).

A unique assemblage for a transnational elite

The combination of all these lines of evidence paints a fascinating picture. The Hastrup treasure is not a random collection of scrap, but the remains of one or several coordinated sets: perhaps the sumptuous attire of a high-ranking woman, a set of equipment for a ceremonial cart, or a combination of both.

The objects were made in the 6th century BC, using rolling and repoussé techniques that were not local to Scandinavia but characteristic of southern workshops. They arrived in Jutland through exchange networks that, despite the transformations of the period, continued to connect the Hallstatt world with the north. The metal traveled, perhaps in the form of ingots or already cast objects, from the Alps, and the tin possibly from Great Britain or Central Europe.

The uniqueness of the clips on the large discs remains a mystery, hinting at the possibility of local innovation or of a specific community style yet to be discovered. The Hastrup treasure is, ultimately, an exceptional testimony to a period of transition, in which raw materials, ideas, and symbols of status circulated over thousands of kilometers, shaping complex cultural identities at the fringes of the Bronze Age.

Louise Felding, Daniel Berger, Charlotta Lindblom, Heide Wrobel Nørgaard, The Hastrup hoard: Metallurgical and typological links between South Jutland and Hallstatt Europe in the 8th to 6th centuries BCE. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, Volume 69, February 2026, 105533. doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2025.105533