The road leading to the discovery of portraits of the governors of Malta is strewn with multiple hazards and a myriad of dead ends. Disappointments abound; trails lead up blind alleys and clues grow cold. However, one recent journey, despite its twists and turns, resulted in an intriguing voyage; one that in turn left many questions unanswered.

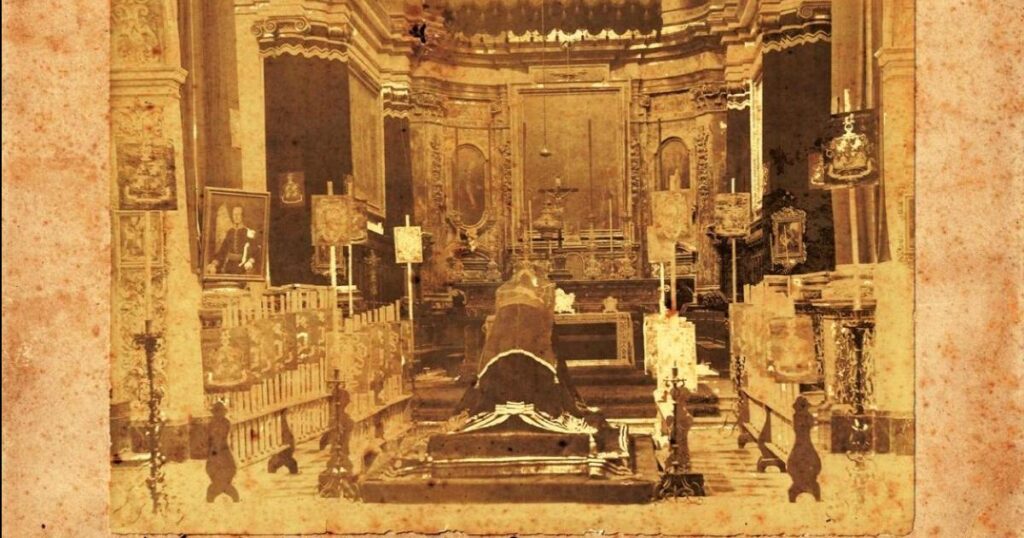

The case in point is that of Governor Richard More O’Ferrall (1847-1851). The journey began a couple of years ago with the appearance of a rare photograph of the interior of St Paul’s Shipwreck collegiate parish church in Valletta. The photograph, reproduced here, is captioned I Funerali del Governatore Civile R. More O’Ferrall and was dated December 14, 1880.

It shows a catafalque erected in front of the main altar, surrounded by other significant accessories borrowed from the Sodalità dei Preti (of the same church) that were customarily used for the obsequies of deceased prelates. A gold-trimmed black pall is draped over the catafalque, on which are placed symbolic mementos of the deceased, such as his sword and cocked hat; over these a gold, tasselled gauze-like veil shrouds the catafalque and serves as a metaphor for death. The surrounding columns are also draped in black fabric and the six large altar candles are of dark-coloured beeswax. The reader might well ask why a foreign civil dignitary merited such devoted reverence.

More O’Ferrall was the first and only Roman Catholic governor of Malta; this meant that, in addition to having a good knowledge of the Catholic Church’s modus operandi, his position as governor gave him direct access to the Vatican hierarchy; a fact that was to prove advantageous to St Paul’s Shipwreck’s collegiate chapter.

Silver mace, St Paul Shipwreck church. Photo Robert Cassar, Courtesy of St Paul’s Shipwreck Church.

Silver mace, St Paul Shipwreck church. Photo Robert Cassar, Courtesy of St Paul’s Shipwreck Church.In recognition of the work carried out by the canons administering to the sick during the plague of 1813, Pope Pius VII granted them the privilege of processing with a mace rather than just a simple silver staff. It turned out that the cathedral chapter, which until that time had not exercised their prerogative of using a mace, took umbrage and put a stop to such usage by the canons of St Paul’s. This dispute rumbled on for many years until More O’Ferrall negotiated between the cathedral chapter and the Vatican, eventually resolving this Gordian knot in 1850.

Having restored their hard-won privileges, the canons of St Paul’s sought to express their gratitude to the late governor with what they viewed as appropriate obsequies. Included in the funerary arrangement was the governor’s portrait (to the left of the catafalque) which merits examination. The portrait was painted by Giuseppe Calleja (1828-1915) and still hangs in the sacristy.

Of the three portraits of More O’Ferrall known to the authors, two show him wearing a uniform. The third, hung in the Malta Chamber of Commerce, which was founded with the governor’s encouragement in 1848, was painted by Giuseppe Calì in 1890, and is thus a posthumous portrait. Besides the sacristy portrait, another likeness of More O’Ferrall is held in a private collection in Malta.

Before we come to an examination of these two uniformed portraits, it is important to point out a peculiarity in More O’Ferrall’s character. The reader will note that in referring to the governor, the appellation “sir” has not been used.

Historians and researchers please note that he was never knighted (nor was he a baronet) and thus does not merit this title. He is unique in this circumstance among the 19th-century governors of Malta, just as his religious persuasion as a Roman Catholic was singular, and thus rendered him the right man for the job, following his predecessor’s entanglement with the Church in Malta (see ‘Sir Patrick Stuart: a striking profile’, The Sunday Times of Malta, November 2, 2025).

More O’Ferrall was a man of high principles, and while he encouraged others to accept honours and awards, he eschewed them for himself. It is More O’Ferrall’s refusal of honours that presents us with the first anomaly in the way he was depicted in the two portraits under consideration: in one of these portraits, the governor is shown wearing the ribband and breast star of a knight commander of the Order of St Michael and St George, which is, as discussed above, incorrect.

The question of why More O’Ferrall would have chosen the uniform of a lower ranked official cannot be easily answered

British colonial governor’s uniform dress coatee, 1850s, England, maker unknown. Gift of Miss P Lowe, 1979. Te Papa (PC001945)

British colonial governor’s uniform dress coatee, 1850s, England, maker unknown. Gift of Miss P Lowe, 1979. Te Papa (PC001945)To be sure, More O’Ferrall was a distinguished politician and administrator; his full and formal appellation at the end of his career as The Right Honourable Richard More O’Ferrall, DL, JP, PC, was adequate proof of this. His post-nominals signify his appointments as deputy lieutenant (DL) of a British county, justice of the peace (JP) and privy counsellor of Ireland (PC); it is the latter appointment that carries the formal address of “The Right Honourable”.

The Privy Council is a formal body of advisors to the sovereign of the UK; it is nowadays composed principally of senior politicians and judges. The appointment was, and still is, for life.

More O’Ferrall was appointed to the Privy Council in recognition of his status as a respected member of the House of Commons. During his 30-year political career, he represented various constituencies in Ireland and served as first secretary of the Admiralty, as well as financial secretary to the Treasury of the UK government.

Lord Lieutenant’s scarlet coatee. Private collection, Malta. Photo: Peter Bartolo Parnis

Lord Lieutenant’s scarlet coatee. Private collection, Malta. Photo: Peter Bartolo ParnisBoth portraits show More O’Ferrall wearing a dark blue single-breasted jacket (coatee) with scarlet Prussian (standing) collar. In the sacristy portrait, where his cuffs are also visible, they too are of scarlet fabric embroidered with a silver oakleaf motif. Both portraits include silver epaulettes.

As governor of Malta, More O’Ferrall would have been entitled to wear a governor’s uniform as shown here, except that the uniform depicted does not include the customary silver epaulettes. To get a better idea of the effect of the full outfit with epaulettes, one can view the scarlet lord lieutenant’s uniform also shown.

More O’Ferrall would have been entitled to wear a deputy lieutenant’s scarlet uniform after his term as governor of Malta. The difference between a lord lieutenant’s and a deputy lieutenant’s uniform is that in the latter case, the buttons were paired vertically. However, More O’Ferrall clearly isn’t wearing this type of uniform, since neither portrait depicts either a double-breasted coatee or the cuff flashes (three-pointed embroidered flaps).

Civil uniform coatee, before 1838. Private collection, Malta. Photo: Peter Bartolo Parnis

Civil uniform coatee, before 1838. Private collection, Malta. Photo: Peter Bartolo ParnisAnother uniform More O’Ferrall would have been entitled to wear as a senior politician in the home government would have been the cabinet minister’s civil uniform, also shown. This is made of blue fabric with silver embroidery and is single-breasted. Unfortunately, this has gold buttons and black velvet cuffs, so we also must discount this.

There was another uniform superior civil officers (members of colonial legislative councils) were entitled to wear. This uniform best matches that which More O’Ferrall is shown wearing in these two portraits.

In the official descriptions of this uniform, dated 1825 and 1843, epaulettes were expressly forbidden; however, a photograph of the original owner wearing this outfit shows him sporting epaulettes, so it may have been the case that epaulettes were permitted in some colonies by the late 1840s when More O’Ferrall’s was appointed governor of Malta.

Superior Civil Officer coatee. Private collection, Malta. Photo: Peter Bartolo Parnis

Superior Civil Officer coatee. Private collection, Malta. Photo: Peter Bartolo ParnisResearch also shows that regional variations did exist in different parts of the British empire, and in many cases, local habits depended on the governor’s predilections. It wasn’t until the civil service reforms of the 1860s that civil uniforms were standardised throughout the empire.

Nevertheless, the question of why More O’Ferrall would have chosen the uniform of a lower-ranked official cannot be easily answered. It may have been a result of his aversion to symbols of authority or, being pragmatic, he may have decided to cut costs and adapt his cabinet minister’s uniform; there certainly were the tailoring and embroidery skills present in Malta that were patronised by the naval and military forces, which would have allowed him to do so.

Then there is always the possibility of artist’s licence. More O’Ferrall left Malta in 1851 and his death occurred in 1880. As this author’s research has revealed, there are few examples of the governor’s likeness in Malta or the UK; one must therefore wonder what sources the artists were working from: their own memory, or the descriptions of others who had most likely not seen the subject for close on 30 years.

Patrick Macgowan wearing his Superior Civil Officer’s uniform. Private collection, Malta. Photo: Peter Bartolo Parnis

Patrick Macgowan wearing his Superior Civil Officer’s uniform. Private collection, Malta. Photo: Peter Bartolo ParnisThe rather naïve style in which these portraits are rendered, especially the sacristy portrait, would indicate that the portrait was commissioned by the appreciative canons, quite possibly in haste, to meet the deadline for the obsequies that would have traditionally been held a month after the death of the subject, and that the artist was working from memory.

Nevertheless, due to the gratitude shown by St Paul’s Shipwreck collegiate chapter, we have a record of a rare event and an intriguing portrait to puzzle over.

Thanks and dedication

The authors thank St Paul’s Shipwreck collegiate church for its assistance in sourcing images for this article.

This article, which had been planned many months ago, is dedicated to the memory of the late Dr Albert Ganado, whose own scholarship in matters Melitensia has been an ever-present inspiration to the authors’ research. Serendipity plays a welcome part in historical research, and in this case it is wholly appropriate that the focus of today’s topic should be the very church in which Dr Ganado’s funeral was held a few weeks ago.