Summary

- Estonia is a small, post-Soviet country with a Russian-speaking minority. It is also one of the most geographically isolated NATO alliance members—and has a direct border with Russia. These characteristics make Estonia the most widely touted target of a Russian invasion of NATO territory.

- However, almost four years of attritional warfare in Ukraine have drained Russia’s financial, personnel and military resources. Its fighting power is diminished and, as things stand, it lacks the capabilities to successfully mount either a traditional military offensive or a hybrid attack.

- Europe’s NATO members (including Estonia’s neighbours) are also in a stronger position to assist Estonia against Russian aggression. Estonia itself has developed a three-pronged defence concept based on traditional artillery, air defence and a well-drilled societal response.

- It will take Russia some 5-10 years after the end of the war in Ukraine to refit and rearm for such an attack. To ensure Estonia’s security, the country and its allies need to continue developing their defence capability now and in the coming years—even if they have minimal assistance from the US.

Russia is scary

In September and October 2025, a string of Russian incursions into NATO airspace—brushing Estonia’s borders, crossing briefly into Romania and violating Polish skies—jolted European capitals. Taken alone, each incident could be dismissed as a navigational error or an act of military bravado. But together, the incursions seem to many in Europe like probes: a deliberate attempt by Russia to test NATO’s resolve and see if the alliance’s response has dulled after almost four years of grinding war in Ukraine.

For authorities in the European capitals affected, the pattern is ominous. It suggests a Kremlin willing to risk calibrated provocations and perhaps even a direct attack on NATO’s eastern flank. “An armed attack on Poland is being prepared”, warned General Wieslaw Kukula, the chief of staff of the Polish Armed Forces in November 2025. “The enemy has begun preparations for war”.

In Europe, this anxiety sits atop a deeper fear: that the American government, distracted by domestic politics and tempted by retrenchment, might soon reduce its presence or attach conditions to its role in Europe’s defence. Such a shift does not necessarily mean that the United States will formally abandon NATO. However, Europeans fear that even modest ambiguity or delay from the US could embolden Moscow to test the alliance’s cohesion: America’s announcement that it will not replace its rotational ground combat brigade in Romania has only reinforced these concerns.

If Russia was to test NATO, Estonia—small and symbolically potent as key frontline state and former Soviet republic—is widely touted as a likely target. First, among all the alliance members, Estonia sits closest to the storm. It is a small, flat and exposed frontier state with a Russian minority, pressed against Russia’s western frontier and within artillery range of St Petersburg.

Second, Estonia is isolated from the rest of Europe by the narrow Suwalki Gap, hemmed in by the Kaliningrad exclave to the south and Russian forces to the east, and lacking the strategic depth that larger states enjoy. This makes it the hardest corner of Europe to defend—a RAND wargame in 2016 concluded that Russia could seize the Estonian capital within 60 hours of an invasion.

Third, Estonia is, not coincidentally, the ultimate test of Western unity: if NATO cannot protect the Baltic state most obviously in the crosshairs, its security guarantees everywhere else will lose credibility. By the same token, if NATO can deter and (if necessary) defeat Russia in Estonia, this shows it can manage even the hardest case.

Such concerns have often roiled European politics. An influential 2025 book by Carlo Masala, If Russia Wins, imagines a successful 2028 Russian invasion of Estonia, just three years after the putative end of the Ukraine war. The European political and analytical community is rife with predictions of when and how Russia will choose to test NATO, with most forecasts focused on 2027 or 2028.We cannot know Russia’s future intent—even the Russian leadership likely does not know its ultimate intentions in the Baltics. But we can have a reasonable assessment of Russian military capabilities now, and for a few years into the future.

This paper examines the threat to Estonia as of late 2025, given the state of Russia’s forces, Estonia’s defences and NATO’s evolving political-military posture. We analyse two scenarios for an Estonian contingency: an outright invasion meant to seize ground quickly and force NATO into paralysis; or a hybrid “in-and-out” campaign that uses local proxies, sabotage and deniable special forces to create temporary faits accomplis under the fog of ambiguity. This report then evaluates both scenarios, drawing on operational-level military analysis, before considering how dependent deterrence remains on the US—and what a credible European-led response might look like, should Washington hesitate.

We conclude that, in contrast to the situation RAND saw in 2016, neither scenario could succeed strategically today or for about five to 10 years after the end of the Ukraine war, even with minimal US assistance. NATO’s task in the Baltics will be harder if the US retrenches from Europe, but it is not impossible even in that circumstance.

Maintaining NATO’s capacity to defend Estonia for more than few years after the war in Ukraine ends is, however, not automatic. But it depends less on the rate of Russian military reconstitution, and more on continued reforms and rearmament among NATO’s European members. Many such reforms have already begun, but they need to continue even after the emergency of the Ukraine war subsides.

The task ahead is therefore to consolidate. NATO needs to rehearse, Europeanise and demonstrate its deterrence. America remains an important ally, but NATO Europe must prove capable of holding the line even if Washington hesitates. Ultimately, a European-led defence of Europe will be more robust than a US-led defence simply because the US is far away and subject to dramatic political shifts on Europe and Russia—as seen under the Trump administration.

The wounded bear

The Russian army that exists today is not the one that once troubled Europe’s northern flank. Three years of attritional warfare in Ukraine have bled it white. Elite formations—Russian Airborne Forces (VDV) units from Pskov and tank divisions from the Moscow and Leningrad Military Districts (known until 2024 as the Western Military District)—are at skeletal strength. Manpower shortfalls, equipment losses and ammunition shortages constrain offensive options. By most estimates Russia has lost hundreds of thousands of personnel, tens of thousands of tanks and armoured vehicles and several fighter jets—while burning through millions of rounds of ammunition and drones.

At the same time, the Russian military is learning from its fight in Ukraine. Judging by the recent incursions, the Kremlin’s tolerance for risk has not disappeared. Many in eastern Europe believe that Moscow remains willing to use force to achieve shock and surprise—especially against a small neighbour whose defence depends on NATO’s political cohesion—and that it can use that force to break NATO unity. Ultimately, we cannot know Russia’s intent. But Europe and its Western allies can have a pretty good sense of Vladimir Putin’s capabilities.

However, in 2025—and at least until a few years after the war in Ukraine ends—the logistical and operational barriers to Russia achieving any political-military objectives in Estonia are formidable. In part this is because defence planning and readiness in the Baltics has not stood still since February 2022. Estonia has learned from Ukraine’s experience—and taken it as a warning.

Since 2022, Estonia has shifted from a strategy of punishing Russia through sanctions and a counterattack if it were to invade towards a strategy of denying Russian forces the capacity to invade. The Estonian government has increased defence spending to roughly 5% of GDP, with over €10bn ($11.5bn) earmarked until 2029. This money is transforming the Estonian Defence Forces (EDF) into one of Europe’s most capable small militaries.

Estonia’s defence posture

Estonia’s new defence concept is built around three core pillars: the first is artillery supremacy. It has acquired South Korean K9 “Kõu” self-propelled howitzers, longer-range HIMARS systems (under joint Baltic procurement) and massed ammunition stockpiles. In any conflict, heavy artillery fire would be used to prevent an aggressor from advancing, both by impeding forward progress by the adversary’s manoeuvre forces, and by disrupting or destroying its supply lines, stockpiles and logistics.

The second pillar is air and drone defence. This is centred on the joint Estonian-Latvian purchase of IRIS-T batteries and the creation of sophisticated drone defences along the eastern frontier, which comprise an integrated grid of sensors, counter-UAS systems and surveillance drones. Estonia has also requested the deployment of a NATO Patriot battery and is looking for other ways to bolster its air defence, especially against ballistic missiles. Estonia relies on the Baltic Air Policing mission through NATO for combat aircraft, though it does have growing air surveillance capabilities.

The third pillar is total defence through the mobilisation of society, which in Estonia numbers about 1.4 million people. The volunteer Defence League (Kaitseliit), which has over 38,000 members, provides immediate territorial defence and urban resistance capacity. In case of an external attack, this reserve force would supplement Estonia’s active-duty force of about 7,000 personnel (including air and naval forces) and another 40,000 citizens who have received military training but have no assigned military role. Overall, Estonia has around 85,000 citizens prepared and willing to mobilise.

Together, these measures have already transformed Estonia’s posture. The country no longer depends solely on NATO’s promise of rescue. It now aims to deny any invader the ability to achieve objectives before allied reinforcements arrive—a strategy that, in light of Ukraine’s battlefield experience, makes military sense.

Lessons of war

Three battlefield lessons from Ukraine, in particular, have informed Estonian and NATO planning for potential Russian military action in Estonia.

Lesson one: defence is stronger than offence. Ukraine has used dense minefields, layered obstacles, swarms of cheap drones and pre-sighted artillery to increase and consolidate the long-time dominance of defence over offensive manoeuvre warfare. Such tactics can halt mechanised formations cold and mean Estonia’s open terrain—forested but flat, with limited road for mechanised forces—could become a lethal defensive trap. In almost four years of war in Ukraine, Russia’s innovative military has not solved or even appreciably reduced this problem. It remains incapable of rapid or broad offensives.

Lesson two: artillery remains the god of war. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has demonstrated how massed fires (artillery and long-range missiles, for instance), coupled with pre-aiming at known targets, real-time drone spotting and counter-battery radar, can decimate even large armoured columns. Estonia’s recent investments in modern artillery systems and precision rounds indicate that its government is taking seriously the need for such upgraded capabilities, even amid the uptick in aerial warfare via drones.

But this is not to minimise lesson three: drones and loitering munitions have revolutionised reconnaissance and strike operations. Cheap first-person view (FPV) drones can destroy tanks; loitering munitions can harass supply lines; small unmanned aerial vehicles provide constant overwatch. The proliferation of drones used by both Russia and Ukraine mean that every movement is observed; every road is a potential ambush. Along the frontline in Ukraine, both sides’ use of drones has created a “kill zone” in which neither side can operate. This is effectively freezing the fight in some places.

The lessons of Russia’s war in Ukraine suggest that small, prepared states now have a greater chance than ever of denying larger, better-armed adversaries their military objectives due to an inherent defensive advantage. This has been amplified by drone technologies and advances in precision munitions. Any aggressor entering Estonia would face constant surveillance, passive and kinetic obstacles, persistent fires and severe attrition before ever reaching Tallinn. Indeed, all three factors make defence cheaper and more lethal.

Estonia’s points of weakness

Of course, Estonia remains at risk due to other reasons. This includes the social vulnerability of Narva and Ida-Viru County, which are home to a large Russian-speaking population that Moscow might seek to exploit. The local people have remained loyal to Estonia, but the region continues to be susceptible to disinformation and agitation. This is because of persistent socioeconomic disparities between the region and the rest of Estonia; limited Estonian-language integration and media consumption that leaves parts of the population dependent on Russian-language information; and the proximity of the Russian border, which enables cross-border influence operations.

The Friendship Bridge spans the Narva river. Ivangorod, Russia is located on its eastern border, with Narva, Estonia to the west. (Picture Alliance. Photo by Krisztian Elek / SOPA Images/Sipa USA)

The Friendship Bridge spans the Narva river. Ivangorod, Russia is located on its eastern border, with Narva, Estonia to the west. (Picture Alliance. Photo by Krisztian Elek / SOPA Images/Sipa USA)

Estonia might also struggle to maintain its logistical, materiel and personnel depth. The country’s supply routes are limited; its depots, though hardened, are vulnerable to precision strikes. Sustaining dispersed forces under drone and artillery attack is difficult, especially given the relatively small size of Estonia’s armed forces. Though Estonia’s military is bigger and better prepared than it once was, it is still too small—and its defence capabilities too limited—to fight a protracted war on its own. This is a function of its small population size and limited economic resources, as well as its challenging proximity to a much bigger neighbour.

Estonia would therefore require external reinforcements in any protracted campaign, though how many and quickly would depend on the size of any Russian invasion force and Estonia’s continued defence investments. Investments in rail and road infrastructure through Poland and the Baltic states will make getting these reinforcements from other NATO member states into Estonia easier in the future—although some planned improvements are not yet complete.

Estonia also needs to consider its air-defence density. Medium-range systems are on order, but full coverage will take time. Low-level drones and cruise missiles could still penetrate. As seen in Ukraine, an inability to defend the skies can be debilitating for any fighting force because it leaves personnel, equipment, supply lines and other strategic targets vulnerable to attack and destruction. In a conflict, a lack of air defences would also put Estonia’s civilian infrastructure at risk, including its energy and communication systems.

Finally, cyber vulnerabilities persist. Estonia’s status as a digital pioneer makes it a prime target for cyber disruption. Coordinated attacks on networks and infrastructure could paralyse early command and control while wreaking havoc on everyday life in Estonia.

These are the potential avenues Russia might try to exploit in either of the two scenarios—outright invasion or hybrid attack—examined below.

Scenario one: Outright conventional invasion

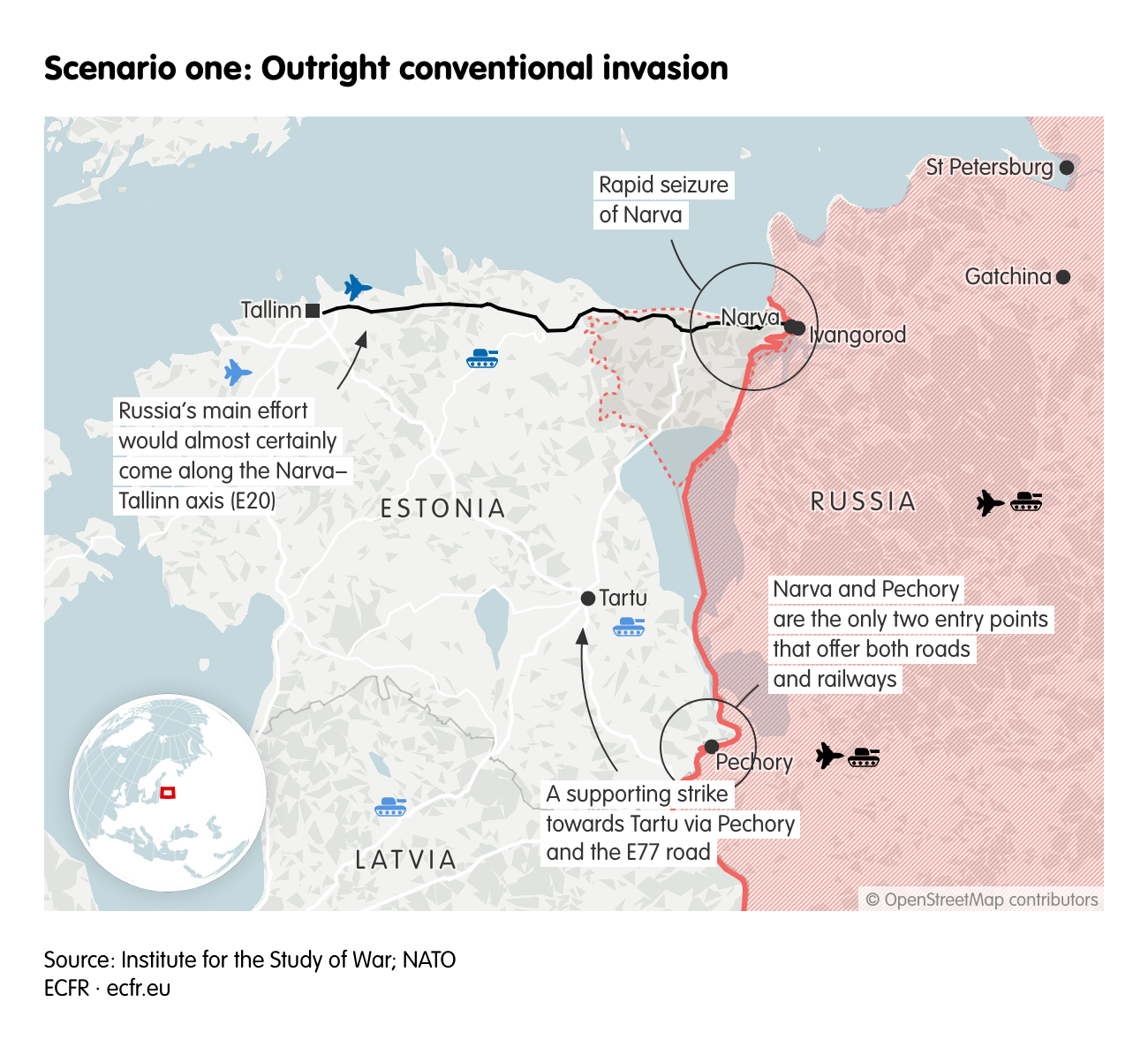

A conventional Russian invasion of Estonia would likely pursue limited objectives—a rapid seizure of Narva, perhaps a drive towards Tallinn—to shock NATO and force a negotiated “pause”. The intention could be simply to undermine NATO and prove that Article 5 commitments on the eastern flank are empty; or to gain territory for Russia to use as leverage to extract other concessions on NATO force posture or other Russian priorities. Given the degraded state of Russia’s forces, even a limited campaign to gain leverage would be a high-risk operation with a narrow window for success.

Russia’s main effort would almost certainly come along the Narva–Tallinn axis (E20): a 210km-long corridor of roads and bridges cutting westwards from Russia, across Estonia’s industrial belt. A supporting effort might strike north toward Tartu via Pechory and the E77 road route, aiming to divide Estonian forces and threaten NATO’s reinforcement routes from Latvia. Narva and Pechory are the only two entry points that offer both roads and railways. There are no other truly viable options for offensive operations into Estonia.

Russian forces available

This type of campaign requires surprise, which is probably difficult to achieve given current NATO attentiveness to Russian military movements. As a result, Russia is likely to rely on its available—and nearby—forces, primarily those in the Moscow and Leningrad Military Districts. On paper, Russia appears to have about 40,000 ground forces located in the vicinity of the Baltic states that might contribute to a conventional invasion of Estonia. Closest to the border is the 6th Combined Arms Army, which has two motorised rifle regiments at Luga and Kamenka. Kaliningrad has one motorised rifle regiment, one motorised rifle brigade and a naval infantry brigade.

Finally, the 76th Guards Air Assault Division is located near Pskov. This has three airborne regiments, part of the elite VDV. Alongside these ground forces, according to the most recent order of battle, the Russia Aerospace Forces might have up to three fighter aviation regiments in proximity to the Baltic region, in addition to reconnaissance, air defence, refuelling capabilities and other aircraft.

As of late 2025, the number of Russian ground personnel and air forces at Baltic air bases is almost certainly many times fewer than what planning documents suggest. Almost four years of war have left the units of the Moscow and Leningrad Military Districts severely depleted. The VDV units and tank units assigned to this region have been decimated, with large portions of their soldiers and equipment deployed to and eventually killed (or destroyed) in Ukraine.

Reports from the Baltic states and Finland also suggest that the Russian military bases nearest their borders are largely empty. Some continue to host armoured vehicle; at others, runways and other military infrastructure have been refurbished, expanded or built from scratch. But Russian forces have, for the most part, not returned in large numbers. We cannot be certain of precisely how many of the supposed 40,000 ground personnel and three fighter regiments of aircraft are currently available for an invasion of Estonia, but we can estimate the upper and lower bounds with some confidence.

For starters, Moscow is unlikely to use its Kaliningrad units for an operation in Estonia. Doing so would leave the exclave defended only by the naval infantry brigade, a risky prospect now that Finland and Sweden have joined NATO, which has allowed the alliance to easily dominate the Baltic Sea. A decision not to use the Kaliningrad forces would be significant because it would reduce by at least 10,000 the number of ground forces available for an Estonia operation; and because it likely means that NATO allies can be less concerned about a Russian attempt to block reinforcements through the Suwalki Gap if required. Given the limited forces available and Kaliningrad’s vulnerability, Moscow is likely to concentrate its military efforts around Estonia only—at least for the limited campaign this scenario imagines.

A border fence between Lithuania and Russia pictured at the Suwalki Gap area, the land corridor on the shared border between Lithuania, Poland and Russia. It is flanked by Russia’s exclave of Kaliningrad to the northwest and its ally Belarus to the southeast. Poland, October 17, 2022. Picture Alliance. REUTERS/Kacper Pempel

A border fence between Lithuania and Russia pictured at the Suwalki Gap area, the land corridor on the shared border between Lithuania, Poland and Russia. It is flanked by Russia’s exclave of Kaliningrad to the northwest and its ally Belarus to the southeast. Poland, October 17, 2022. Picture Alliance. REUTERS/Kacper Pempel

Of the remaining 30,000 Russian soldiers that should be in and around the Baltic region, eye-witness accounts and satellite imagery suggest that half remain at most. Russian soldiers are rarely seen near Estonia’s borders these days, for instance. Much of Russia’s aerospace forces are now focused on operations in Ukraine and Russia has moved some aircraft to locations further out of reach of Ukrainian attacks. This makes it reasonable to assume that less than half of Russia’s usual complement aircraft are still at their bases in the region around Estonia.

This matches reports from Estonia’s Foreign Intelligence Service which indicate that Russian garrisons directly behind the borders of Estonia, Finland, Latvia and Lithuania are “mostly empty”, and that Russia has deployed the forces which should be stationed there to Ukraine. It is reasonable to assess that around two motorised regiments and some airborne and artillery detachments might remain on Russian territory in close proximity to the Baltic region (likely understrength). They are probably accompanied by one or two fighter aviation regiments (about 90 to 100 aircraft) plus some air defence, reconnaissance, refuelling capabilities and early warning aircraft.

The resulting 15,000 or so ground personnel and 90-100 fighter aircraft offers a reasonable upper bound of what Russia could cobble together for a conventional invasion of Estonia. However, it is likely that the Russian reality is significantly more meagre. According to an interview with a Western official, intelligence estimates as of late 2025 assess that Russia retains only two brigade tactical group equivalents near Estonia, both understrength and tasked mostly with territorial defence duties.[1]

Using an estimate of two battalion tactical groups (BTG), supplemented by some nearby airborne and artillery detachments, then the true number of Russian forces available for an operation might be closer to 5,000 personnel. This is a third as large as the upper bound estimate. The total airpower available might also be lower than 100 aircraft—potentially only 40 or 50 fighter jets at any one time.

Of course, in planning such an offensive, Moscow would have the option of turning to other regions beyond the Western Military District for reinforcements. But it is unlikely to do so. First, it is not clear that other military districts are any better off when it comes to available personnel, or that they could contribute forces to an operation in Estonia without compromising Russia’s other security needs.

Importantly, any effort to increase the number of Russian soldiers based near Estonia would trigger alarm bells across NATO. On first sight of Russian troop movements, Estonia would likely mobilise its reserve and civil defence forces, and preparations for reinforcements would begin across the alliance. In this case, losing the element of surprise almost guarantees failure, given the weakened state of Russia’s military and limited forces available for an Estonia offensive.

The operation

Challenge one: River crossing

The opening phase of a Russian invasion into Estonia would likely involve intense electronic warfare and standoff strikes. Russian batteries near Ivangorod and Gatchina could fire long-range artillery and missiles to suppress Estonian command centres and air defences; drones would provide overwatch while combat engineers attempt to bridge the Narva river under fire.

Russian efforts to bridge the Siverskyi Donets river in Luhansk Oblast and Seim river in Kursk Oblast in Ukraine have demonstrated just how hard such an effort would be. Bridging is generally evaluated to be among the most difficult of military operations, even under the best of circumstances—now consider the presence of drones, which also require specialised combat engineers. Drones not only eliminate the element of surprise; they attrit military forces executing the operation, derail any progress these personnel achieve and destroy convoys as they cross any bridges that are successfully constructed. At the Siverskyi Donets river in 2022, Russia lost an entire BTG in its unsuccessful bridging attempt.

Challenge two: Open terrain

If Russia’s forces did make it across the Narva river, they would still need to advance 200km through open terrain under near-constant surveillance. Here, Estonia’s geography would work against them: the Narva corridor is narrow, dominated by urban terrain and pre-registered artillery zones (artillery zones with pre-defined targets). Every bridge and choke point is known to the EDF and marked for destruction at H-hour. Within the first 12 hours, Russian vanguards would face layered minefields, kill zones covered by K9 howitzers and saturation by FPV drones.

Russia’s daily sustainment requirement—nearly 200 short tonnes per BTG—would strain logistics, especially once NATO airpower and drones began interdicting convoys. As Ukraine has shown, even a small artillery battery can immobilise entire armoured columns once supply lines are exposed. And time is also Russia’s enemy. To succeed, the invaders would need to seize Narva and penetrate at least 100km inland within 48 hours, before heavier reinforcements arrived from nearby NATO allies. Every hour of delay would tilt the balance towards the defenders. Drone surveillance, precision artillery and NATO airstrikes would convert the advancing columns into kill boxes.

Challenge three: Attacking the defenders

Estonian army forces would soon meet Russia’s advancing ground forces. And Estonia’s reserves can mobilise rapidly: in the snap exercises which Estonia holds several times a year, the transition from government decision to reserve-force assembly can happen in 24 hours. In the event of a real Russian invasion, the process would happen at least this quickly. Estonia is a small country and light ground forces could be in Narva just a few hours after receiving an order to report.

Estonia’s wartime strength is estimated at about 43,000 ground forces, including one heavy (armoured or light mechanised) brigade and one light (infantry) brigade. A conservative estimate suggests that half of these forces would be ready to fight within the first 12-24 hours, even as the remainder of the reserves continued to assemble, with more forces joining the fight over the course of the second day. Within 36 hours, Estonia could likely have both its brigades engaged in battling a Russian invasion force, with around 25,000-35,000 personnel participating.

This force would be at least twice as large as the Russian contingent, possibly up to seven times as large if the Russian strength is at the low end of the estimated range (up to 5,000 personnel and around 40-50 aircraft). Even if only half of Estonia’s forces arrived in Narva, the 21,500 personnel would be one-and-a-half to four times larger than Russia’s invading army. If Russian forces chose to divide their assault along a northern and southern route (Narva and Pechory), Estonian soldiers would also split up—but maintain a numerical advantage over Russian units in both locations. A southern invasion axis would also make external reinforcement of Estonian forces easier, as units from other Baltic states could arrive quickly.

Rules of thumb used by military planners typically estimate that a successful offensive requires that the aggressor have two to three times as many forces as the defender. In this case, if only half of Estonia’s wartime force arrives in time, Russia would need 44,000-66,000 soldiers to accomplish even the limited offensive outlined here—certainly more than is available today. The experience in Ukraine implies that heavy and effective use of drones on Estonia’s part might push these numbers still higher.

Challenge four: Allies in reserve

Russia’s only hope, then, would be to catch Estonian forces entirely off-guard, cross the Narva river quickly and make rapid progress inland, before even a small (10,000 or so) contingent of Estonia’s military force had time to assemble. Then Russian forces, as the defender, would have to try to exploit their own advantage by retaining any seized territory even as Estonian and NATO reinforcements arrive. But this scenario is unlikely—Estonia could meet this 10,000-person target with just its active-duty force and small portion of its high-readiness reserves, thereby thwarting any Russian attempts to traverse the Narva river to progress inland.

Estonian forces can also expect rapid support from members of the Baltic Joint Expeditionary Force (comprising the other Baltic states, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden and Britain). These reinforcements would almost guarantee that Estonia could repel or dislodge any Russian soldiers who have gained a foothold. Even if Tallinn’s worst fears came true and Washington hesitated to send in US ground-combat brigades, heavy reinforcements from nearby European NATO countries could arrive by the 48-hour mark, if not sooner.

Latvia and Lithuania each have one heavy brigade and additional infantry forces. Fearing that Russia plans to move on them too, neither might be willing to send too many forces into Estonia. Together, however, they could likely contribute at least one additional heavy brigade. NATO would also mobilise its Enhanced Forward Presence Battlegroups forces in the Baltic states, offering at least several heavy battalions and possibly another brigade.

Furthermore, Poland has 13 heavy brigades and could likely offer several additional mechanised and artillery units if necessary. Though their arrival might take longer than 24 hours, Poland would have an incentive to respond in some way, especially if Warsaw feared that a successful Russian campaign in the Baltics would leave its own territory more vulnerable.

Challenge five: Covering all bases

One concern is that Russia would try to block reinforcements from arriving by opening a secondary attack axis along route E77. However, given the limited Russian forces available for this operation, Estonian soldiers along with early-arriving reinforcements from other Baltic states should be able to keep this corridor open. Even if Russia allocated several thousand personnel to such an effort, the equivalent of one heavy brigade (3,000-5,000 soldiers)of Estonian and allied forces should be enough for this task. Moreover, if Russia did split its forces, fewer Russian soldiers would be operating in and near Narva, reducing the allied requirements in that area.

Russian ground forces would not receive much relief from the air. Instead, Russian airpower would struggle to achieve air superiority and likely be overwhelmed by NATO fighter aircraft. Sticking with the assumption that 40-100 Russian fighter aircraft could support a Russian offensive in Estonia, NATO countries could be reasonably certain of at least contesting the skies over Estonia if they can rally at least 30-40 fighter aircraft of their own (though 50-60 would be better). Drones and anti-aircraft missiles launched by Estonian forces would assist NATO aircraft in their efforts to keep Russian fighters from targeting NATO ground forces and infrastructure or providing cover to Russian ground forces at key points such as the Narva river crossing, especially in the early hours of the invasion.

F-16 fighter jets fly over Kucova, the newly rebuilt NATO air base, in Kucova, Albania, March 4, 2024. Picture Alliance. REUTERS/Florion Goga

F-16 fighter jets fly over Kucova, the newly rebuilt NATO air base, in Kucova, Albania, March 4, 2024. Picture Alliance. REUTERS/Florion Goga

Within minutes of Russian forces crossing into Estonia, NATO fighters at Amari (Estonia), Lielvarde (Latvia) and Siauliai (Lithuania) could respond. The Baltic Air Policing mission has 4-12 aircraft across the three sites, which could begin immediately attacking Russian positions. As soon as authorised, likely within hours, allied aircraft from the Nordic states and Poland could join the fight, offering air interdiction, early warning, and targeting of Russian logistics and supply lines. Together the Nordic states and Poland have 17 squadrons of fighters available, amounting to over 200 aircraft. If half of these responded to the incursion in Estonia, this would give NATO at least 100 fighter aircraft, enough to reach or surpass parity with Russia’s aerospace forces. This would prevent Russia from achieving air superiority. In fact, NATO itself could dominate the skies.

Russian naval operations to support its ground operation are also unlikely. Moscow’s Baltic Fleet could threaten coastal strikes, but any amphibious landing near Tallinn or the western islands would be suicidal in a sea now dominated by NATO after Finland’s and Sweden’s accession. Even under the best of circumstances, amphibious invasions are among the most difficult attempted by modern militaries. Few such operations are successful in the absence of air superiority, which Russia would almost certainly not have. Any effort to move from the sea onto Estonian territory would be easily spotted and countered—whether by land-based artillery fire, airstrikes or allied naval forces in the Baltic Sea.

Likely outcomes and responses

Militarily, this scenario is untenable for Russia. A conventional invasion of Estonia in 2025 (and for several years after the end of the war in Ukraine) would end not in victory but in strategic disaster. Russian forces might achieve a brief penetration, perhaps capturing parts of Narva or Kohtla-Jarve within 24-48 hours. But they would then stall and face catastrophic attrition at the hands of allied ground and air forces. Within days, Russia would face the choice of withdrawal, annihilation or escalation into full-scale war with NATO—assuming Moscow has the resources for such an escalation, which it does not as long as the Ukraine war continues.

Notably, the successful NATO defence imagined here does not rely on an immediate or decisive US response. Reinforcements from the Baltic and Nordic states and Poland should see Estonia able to halt a Russian advance and overwhelm Russian forces—either by wiping them out entirely or by forcing a hasty retreat within a matter of days. That Estonia can count on immediate support from this small group of allies, which can all respond quickly and have a direct stake in preventing Russia from achieving success in Estonia’s north-eastern corner, seems reasonable. Moreover, NATO’s Article 5 response (likely triggered the moment allied troops in the Enhanced Forward Presence battlegroup came under fire) could make many more forces, including aircraft and ground brigades from Germany, available within a few days.

A Russian offensive that occurs in the next few years would require certain types of US participation. US intelligence, logistics and strategic enablers like aerial refuelling would be necessary. It is realistic that America would provide such support to Estonia after offering Ukraine extensive military assistance, intelligence sharing and some logistics support during its war with Russia. This includes organising the airlift and transport of military hardware destined for Ukraine’s eastern front.

Similarly, the Trump administration gave Israel air-defence assistance and possibly supported air refuelling operations during its 12-day war with Iran, even though Israel is not formally a treaty ally. Notably, by providing even minimal assistance to Estonia, America would thwart Russia’s main political objective: to find and exploit cracks in the NATO alliance.

Scenario two: Hybrid “in-and-out” campaign

Far more plausible than Russia’s direct invasion of Estonia is a hybrid attack: a rapid, deniable operation blending local proxies, cyber sabotage and limited Russian incursions. The goal would be political shock, not territorial gain: to create confusion, delay NATO’s decision-making and demonstrate Western impotence and disunity.

A hybrid campaign, following the model in Crimea 2014, would begin with information and cyber shaping. Russian disinformation networks would amplify grievances in Ida-Viru County, alleging discrimination against Russian speakers. Cyberattacks could disable local power grids or municipal services, creating confusion. Small pro-Russian groups—real or fabricated—might stage protests or riots in the border city of Narva. At a pre-chosen moment, these disturbances would coincide with armed action.

Local cells, coordinated by GRU handlers, could try to seize municipal buildings, police stations or bridges. Within hours, masked men in unmarked uniforms—Spetsnaz or VDV detachments—might cross from Ivangorod under the pretext of “protecting Russian citizens”. A single company-sized force (150-300 troops) could attempt to secure key sites (the Narva bridge, a substation or an airstrip) backed by artillery fire from across the border and drone reconnaissance overhead.

From Russia’s perspective, the aim would be to present NATO with a fait accompli before attribution is clear. Moscow would claim a “local uprising,” call for restraint and propose negotiations. The entire operation would last no more than 48 hours—long enough to create headlines and sow doubt, but short enough to avoid open war. Such an operation depends on three things: speed, deniability and local complicity. But Estonia’s defence environment is now hostile to all three.

Enter the grey zone

Challenge one: Convincing the population

First, attribution will be instantaneous. NATO’s integrated Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance network—satellites, signals intelligence, drones and open-source tracking—would identify Russian involvement within hours. Second, the local population in Narva is not insurgent. Polling since 2022 shows an overwhelming rejection of Russian war narratives. Even if a few agitators acted, they would find little mass support.

Finally, Estonia’s police, defence league and army units now train jointly for precisely this scenario. In the near term, Estonia has plans to establish a 200-person military base in Narva that would speed up any response. With just these 200 active-duty forces, along with rapid-response reserve detachments located nearby and its border police, Estonia has plenty of forces and firepower available. It could isolate and neutralise local threats within hours of an alert that some sort of hostile, grey zone takeover was under way.

Challenge two: Successful infiltration

Tactically, Russian detachments inserted into Narva would face lethal density. Urban warfare is notoriously complicated and, like warfare in more open terrain, heavily favours the defender. US urban combat operations in places like Iraq illustrate how just a handful of defenders can thwart the advance of even a much larger, better equipped offensive force. In Estonia, urban zones are pre-surveyed for artillery fires; defenders can seal them off with FPV drones and precision mortars. Any exfiltration route—across bridges or via helicopter—would be under drone surveillance. Within 24 hours, the invaders would be pinned, low on ammunition and exposed to public identification, all before the bulk of Estonia’s forces had arrived in Narva.

If NATO intelligence confirmed the presence of Russian troops in Estonia, the alliance would move rapidly from Article 4 consultations to Article 5 readiness. NATO air assets would be deployed (just the Baltic policing forces would likely be sufficient in this case to counter such a small Russian grey zone contingent); cyber forces would retaliate (in this Estonia is a NATO leader); and Russian positions across the border could face suppression fire. The grey zone Moscow hoped to exploit would collapse into black and white. And importantly, European dependence on US support would be even more limited than in the case of a full-scale invasion.

Challenge three: Russia outnumbered

Overall, a hybrid “in-and-out” operation remains more plausible than a full invasion, but only marginally. Its success would depend on surprise and confusion, both of which are harder to achieve today than in 2014, when Russia took Crimea. Estonia’s counterintelligence, border control and community resilience have improved dramatically. Its border police, for example, is equipped with advanced technology, drones and sensors that would allow it to almost immediately detect and identify any sort of abnormal presence near the country’s borders. Given the lack of Russian forces in the area over recent years, any sort of activity would likely be spotted immediately.

Placards and posters are displayed along the perimeter of the former Russian embassy in Tallinn, December 6th 2025. (Picture Alliance. Photo by Artur Widak/NurPho)

Placards and posters are displayed along the perimeter of the former Russian embassy in Tallinn, December 6th 2025. (Picture Alliance. Photo by Artur Widak/NurPho)

Likely outcomes and responses

There remains a very small likelihood that Russia could seize and hold even a single town for more than 24-48 hours without being exposed and expelled. Even a quick military failure on NATO’s part, however, could achieve some political disruption. Moscow could spin a temporary incident—a firefight in Narva, a blackout in Tallinn—as proof that NATO cannot control escalation or achieve unity in the face of Russian ambiguity. That, rather than territorial conquest, is the true danger.

To counter this risk, some kind of rapid NATO response would be important, even just for signalling purposes. Estonia could likely suppress a grey zone-type campaign on its own, but a quick reaction from NATO aircraft, mobilisation of at least infantry forces in nearby states, and US intelligence, cyber and command and control support would reinforce the alliance’s unity. If truly necessary, NATO forces stationed in the Baltic states as part of the Enhanced Forward Presence mission could be moved into Estonia to offer additional reinforcement.

America’s diminished role

The bottom line is that even with limited US involvement, Estonia and European NATO allies could halt and likely decimate a Russian ground invasion intended to seize part of Narva. Similarly, Estonia’s coordinated territorial defence, cohesive society and support from NATO’s ISR network would be prepared to counter Russia should it attempt to mount a hybrid campaign. Simply put, in 2025, the Russian army lacks the manpower, logistics and air cover to sustain a 100-200km offensive under NATO fire.

As such, if the US was delayed in its provision of military support, it would not doom Estonia’s defence in the first scenario described above. European states are not without their own capabilities, including strategic enablers: they have several dozen dedicated air tankers, for instance. While this is not a large fleet, it is sufficient to support the limited operation described. European states also have close to 50 satellites focused on military intelligence collection along with civilian satellites, reconnaissance aircraft and other means. Estonia would not be totally blind without US support.

The bigger problem for Estonia’s defence lies in the European ability to exploit the intelligence it collects, particularly due to barriers in intelligence sharing across countries. This is a solvable problem, however. In a true regional crisis, necessity will likely create the political will necessary to push Europe forward in this area. Europe is also dependent on the US for strategic lift. However, European demands on this capability—especially in the early days of a Russian invasion of Estonia—will be limited given that most forces for the operation can be sourced from nearby.

Europe is perhaps most reliant on US leadership for command and control. But even if American political decision-makers hesitated on how much support to provide for Estonia’s defence, NATO would likely immediately mobilise its command systems to support European-led operations. It is unlikely that US policymakers would object, given that these systems are in place and would entail only limited US involvement. The EU also has a command-and-control structure which, while weaker than that offered by NATO, could be exploited in a pinch.

Finally, European NATO allies might also require US-led weapons resupply if an operation to drive back Russian forces takes longer than a few days. This is especially when it comes to munitions, such as air-launched missiles, air defence interceptors and other types of ammunition.

Some will argue that, even with the military balance stacked against it, Moscow could achieve a political win if Washington delayed or limited its support in any way. That hesitiation would undermine European belief in the value of NATO and US support, and weaken the alliance. But even this is unlikely in the next several years. European NATO allies would not need much US assistance to counter a Russian invasion of Estonia—even if Washington hesitates to send ground forces, it is likely to provide the types of enabling support on which Europe still depends. For Moscow, this outcome would be a military and political disaster that could threaten Putin’s regime. Moscow will likely seek subtler, more ambiguous ways to test NATO instead.

The strategic clock

The next few years will present a unique balance. As long as Russia remains tied down in Ukraine, which could be for just another few months or perhaps for many years, it constrains its capacity to project power elsewhere. But this constraint will not last indefinitely. When the fighting stabilises or ends, Moscow will begin to reconstitute its forces. It is possible (though not guaranteed) that with a stronger, rebuilt military force, Russia will be tempted to test NATO. Estonia and its allies therefore have a strategic window, lasting between five and 10 years after the Ukraine war ends, in which to lock in the defensive advantages they currently enjoy.

This means NATO needs to accelerate ongoing reforms: complete air-defence integration; harden logistics and the infrastructure required to rapidly move tanks and other heavy materiel to NATO’s eastern edge; stockpile munitions of all types; and deepen social resilience, particularly in the Baltic states. But perhaps more importantly, it also means ensuring that effective deterrence no longer depends solely on the speed of US decision-making.

In limited scenarios like the two examined here, whereby Estonia faces a constrained and weakened Russian adversary, European NATO members can almost achieve this level of self-sufficiency (though they would likely still benefit from US intelligence, command and control, and logistics support). The alliance’s goal, however, should be the ability to fight, and to signal resolve, on European initiative from hour one of a potential invasion—even after Russia reconstitutes its force and returns in full to bases along its border with NATO.

The distinction between US-led and Europe-led NATO responses to a potential future test by a reconstituted Russian military is now central to strategic planning. Under current NATO plans, in a scenario in which the US is fully engaged, the alliance could detect, attribute and counter Russian aggression—whether conventional or hybrid—with relative ease. America’s Airborne Warning and Control Systems and ISR would saturate the Baltic skies; US fighters and long-range fires would destroy any lodgement before it could consolidate. US ground forces would arrive with reinforcements in under a week and Washington’s political leadership would unify allies. Under these conditions, any type of Russian incursion into Estonia would collapse within days.

If, however, Washington were hesitant or distracted, the early burden would fall on NATO Europe. This prospect is not as bleak as it once was: Poland now fields one of Europe’s largest armies; Finland’s and Sweden’s NATO membership allows the alliance to easily dominate the Baltic Sea; France, Germany and the Nordics are ramping up ammunition and air-defence production. Europe can contest the airspace, interdict logistics and reinforce Estonia within 48 hours, and certainly by the 72-hour mark. Europe also has intelligence assets and some command-and-control systems that it could use to support its own defence.

Still, without Washington, the political process of reaching consensus could also be longer, extending response times. In the above two scenarios, relying only on European capabilities would likely elongate Russia’s window for penetration into Estonia by a day or two. While this is likely not long enough to change the outcome, such a delay could potentially be more impactful if it were extended or in the case of a full-scale invasion that takes place after Russia has fully reconstituted its forces. What Europe does still lack are two capabilities that only the US can provide at scale: strategic lift and deep precision strike. These contributions were not essential in the scenarios considered here but will be once Russia reconstitutes and can mount a larger invasion force. These are gaps Europe must work to fill with some urgency.

For Estonia, the policy prescription is clear: build a defence that assumes European leadership for the first 72 hours and treats US entry as decisive acceleration, not salvation. If Tallinn and NATO Europe can hold that line, deterrence will prevail even despite shifting American attention.

Tomorrow’s problem

Estonia today is both vulnerable and safe. It is vulnerable because of geography, and it is safe because of its preparations and Russia’s weaknesses. Russia’s airspace provocations may be unsettling, but they are symptoms of its limitations, not its strength. Neither a conventional invasion nor a hybrid “in-and-out” campaign offers Moscow a realistic path to success in the next several years. The former would end in disaster; the latter in embarrassment. But both could still wound—politically, economically, psychologically—especially if Estonia and its allies grow complacent or remain too dependent on the US in the future.

European NATO allies can take several specific steps today to ensure their defence is robust—no matter what the future holds.

- European countries need to agree on which threats they are most concerned about, and for which scenarios they should most urgently prepare. Right now, there is widespread disagreement among European officials on what type of challenges European member states should be focusing on (and their timeline) when it comes to military rearmament, procurement and training. A conventional attack on a frontline state is likely to be one of these high-priority scenarios, but various types of hybrid campaigns may may also feed into a shared definition of requirements.

- European NATO members should focus on meeting capability targets set for them by NATO and reducing their dependence on the US. This will mean investing first and foremost in building an independent strategic lift capability and a stockpile of deep-strike missiles, along with the intelligence and targeting assets to make use of both. As noted above, though Europe might want more satellites and reconnaissance aircraft, what it needs most is the ability to share and integrate information across borders.

- Europeans should prioritise the development of command-and-control systems and processes that they can operate without US support. While these could occur through the EU, another option is for Europe to assume responsibility for command-and-control functions inside NATO.

- Europe should also look to take leadership positions within NATO. Going beyond building more robust and integrated defence capabilities, this could eventually include the Supreme Allied Commander role but might start with other institutional leadership positions at lower levels. It will be challenging to make these leadership transitions, such as managing control of US nuclear weapons (a SACEUR responsibility that the American military might retain) but these are surmountable with discussion and time.

- European capitals should ground their military planning firmly on what they can achieve within the next 5-10 years—and also a realistic assessment of what Russia can and cannot do in the same timeframe. Europe has plenty of time to build the military capacity required to defend itself without America and has significant advantages over Russia in many areas. Most importantly, it can start now (and to a degree already has), while much of Russia’s reconstitution will need to wait until its war in Ukraine comes to an end.

If there are any lessons to be learnt from four years of war, it is that Russia is not ten-feet tall and Europe is not entirely hopeless. And for now, the frontier holds. The war in Ukraine has also taught Estonia, and the alliance, that defence—when properly built—can hold back mechanised formations and even hybrid attacks.

For Europe’s NATO members, this should be a source of comfort and security. Even small states that border Russia like Estonia do not need to fear imminent Russia aggression. Such an invasion is unlikely in the near to medium term—but Estonia and its European partners can handle it on their own if it did. The challenge is to ensure that this lesson remains true not only today, while Russia is wounded, but tomorrow, when Russia could again have the capability to test the West.

About the authors

Jennifer Kavanagh is a political scientist with a focus on US national security and defence policy. Her research looks at US military strategy, force structure and defence budgeting, the defence industrial base, and US military deployments and interventions.

Previously, Kavanagh was a senior fellow in the American Statecraft programme at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. She also worked as a senior political scientist at the RAND Corporation, where she led projects for defence and national security clients. She served for three years as director of RAND’s Army Strategy programme. Her work has been published in Foreign Affairs, the New York Times, Foreign Policy and the Los Angeles Times among other outlets.

Jeremy Shapiro is director of research at the European Council on Foreign Relations and a non-resident senior fellow at the Brookings Institution. He served at the US State Department between 2009-2013.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank numerous colleagues and officials who contributed, at times unwittingly, to this paper. In particular, we would like to thank Nicu Popescu, Jana Kobzova, Jeremy Cliffe, Marta Prochwicz Jazowska, Rafael Loss, Nick Witney, Ben Friedman and Michelle Newby for careful reads and helpful comments. We would also like to thank Amy Sandys for brilliant editing that makes us appear comprehensible, and Nastassia Zenovich and Chris Eichberger for stunning graphics that make us appear visually appealing. Any mistakes in the paper remain, however, our responsibility.

[1] Author interview with Western intelligence official, September 2025

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.