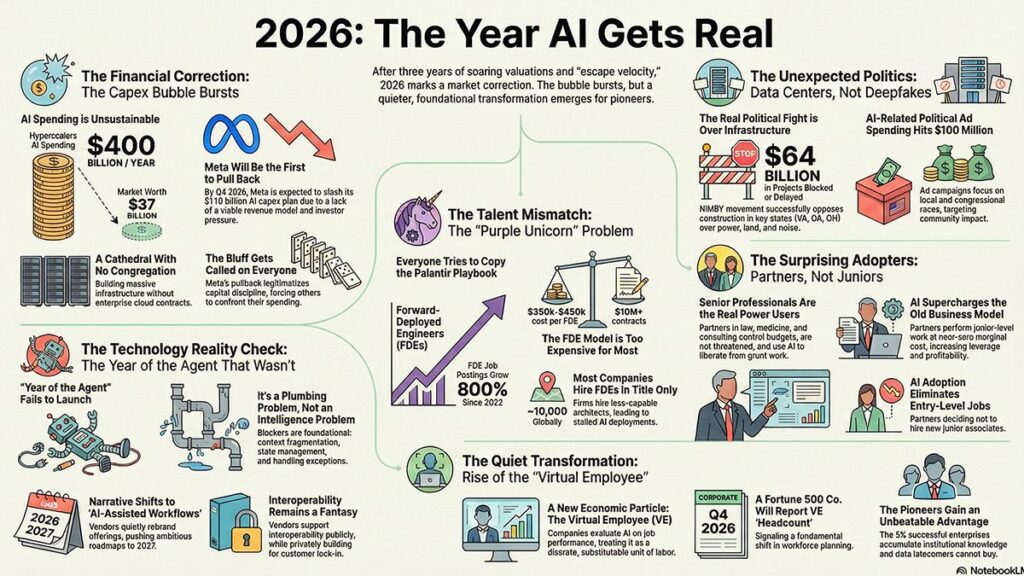

A field guide to the correction, the politics, and the quiet transformation underneath

By the end of 2026, we’ll look back and realize the year wasn’t about AI at all. It was about gravity.

For three years, the AI industry operated at escape velocity. Valuations that defied arithmetic. Roadmaps that promised autonomous everything by next quarter. A cultural moment so frothy that sports betting, meme stocks, crypto, and AI startup funding all drew from the same psychological well: the collective conviction that number go up is its own thesis.

Then came 2026. And gravity reasserted itself.

The Bubble Within the Bubble

Meta throws in the towel on AI capex by Q4 2026 as part of spending pullback.

Here’s the setup: Americans now wager $150 billion annually on sports, up from $4.6 billion in 2018. Zero-day options—the Wall Street equivalent of a scratch ticket—are 62% of S&P 500 options volume. Meme stocks don’t even make the news anymore. We’ve built an entire financial culture around not doing math.

The math doesn’t work. Everyone knows. Nobody cares. The story’s too good—until it isn’t.

The math doesn’t work. Everyone knows. Nobody cares. The story’s too good—until it isn’t.

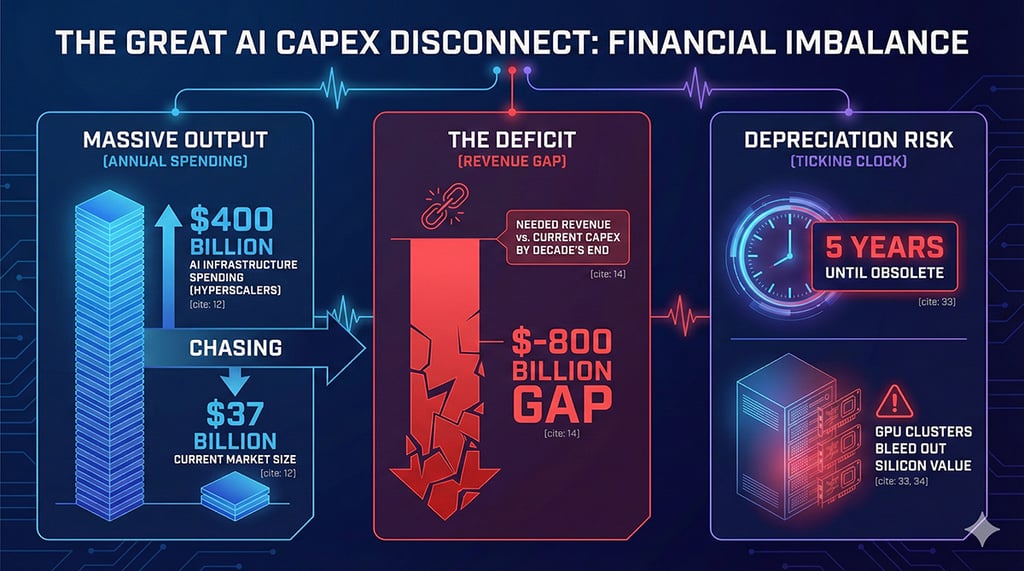

Which is how you get hyperscalers spending $400 billion a year on AI infrastructure to chase a $37 billion market.

Someone at Bain ran the numbers. To justify current capex, AI needs $2 trillion in annual revenue by decade’s end. Best-case forecasts say $1.2 trillion. That’s an $800 billion gap. Everyone knows. Nobody cares. The story’s too good.

Until Meta.

Meta is spending $70-72 billion in 2025, projecting $110 billion in 2026. Revenue model? “Better ad targeting.” Cloud business? None. Direct AI revenue? Zero. Strategy? Fuzzy acquihires and billions spent on superintelligence. They’re building the same infrastructure as Amazon and Microsoft—without the enterprise contracts that make it pay.

When Meta raised capex guidance in October, the stock dropped 11% in a day. Same announcement that sent Amazon soaring. The market did arithmetic for one brief, terrifying moment. Then it went back to vibes.

But Zuckerberg has already told investors he’ll “simply pivot” if the strategy fails. He’s done it before. The 2023 “Year of Efficiency” wasn’t discipline. Massive layoffs correcting pandemic hiring was retreat dressed up as strategy. It worked. The stock tripled.

The prediction: Same playbook, 2026 edition. By Q4, Meta announces “optimization.” Free cash flow will be cratering. Reality Labs will still be bleeding $4 billion a quarter. The obscurely named TBD Labs will seem aimless. The math will be undeniable. Wall Street will applaud the “discipline” of throwing in the capex towel. The stock will rally.

And then everyone else must answer the question: If Meta’s capex didn’t make sense, does ours? Meta won’t just reduce spending — it will legitimize the idea that AI capex discipline is not heresy.

Amazon’s capex is 100% of operating cash flow. Microsoft’s capital intensity is approaching 2000-telecom-bubble levels. The difference is they have cloud meters running. Meta was building a cathedral with no congregation.

The technology is sound. The capital structure is not. And when the most exposed player folds, the bluff gets called on everyone.

One more thing the gambling mindset misses: chips depreciate. The GPU clusters being installed today will be obsolete in five years tops. If agent orchestration takes four years instead of two, a lot of silicon bleeds out before the use case arrives. The hyperscalers aren’t just racing adoption. They’re racing their own depreciation schedules.

Meta will be the first to admit it. They won’t be the last.

The Year of the Agent That Wasn’t

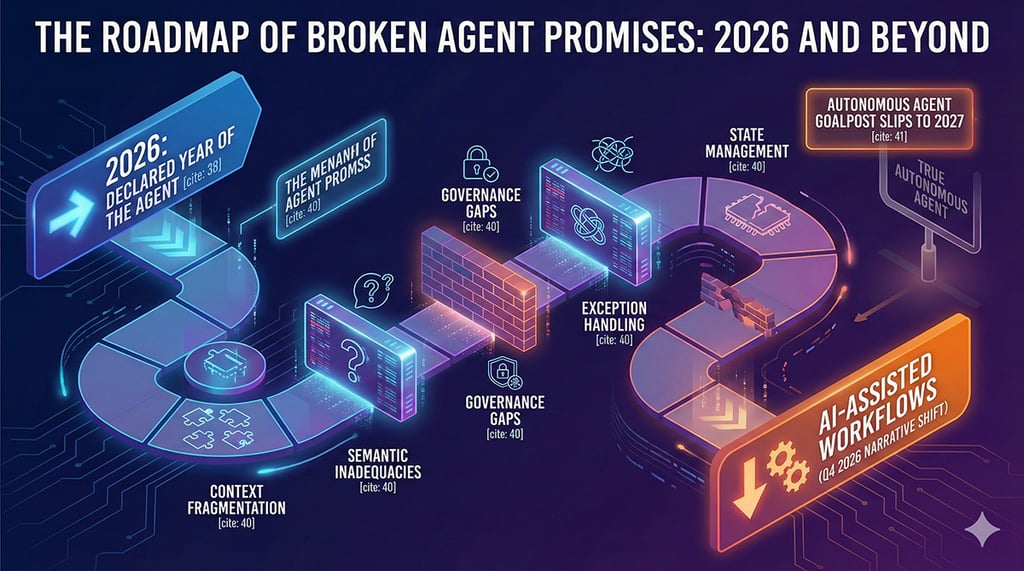

Despite the lack of progress in 2025, the industry will declare 2026 to be the Year of the Agent. It still won’t be.

Every quarter will bring a new blocker—context fragmentation, semantic inadequacies, governance gaps, exception handling, state management—each one “almost solved” and never quite resolved. By Q4, the narrative will quietly shift from “autonomous agents” to “AI-assisted workflows,” and vendor roadmaps will slip to 2027.

It’s a plumbing problem, not an intelligence problem. And plumbing takes time.

It’s a plumbing problem, not an intelligence problem. And plumbing takes time.

This isn’t a technology failure. The LLMs can reason well enough. What they can’t do is understand context across system boundaries, maintain state across sessions, appreciate what different data means to different systems, handle the long tail of exceptions, or operate within governance constraints. These are plumbing problems, not intelligence problems. And plumbing takes time.

Meanwhile, the alphabet soup of multi-vendor protocols—MCP, A2A, ACP, and whatever Google announces next—will achieve “growing ecosystem momentum” in press releases and zero production deployments at scale. The incentives are misaligned. Every hyperscaler says they want interoperability while building for lock-in. Salesforce wants agents that orchestrate within Data 360. Microsoft wants agents that live in Fabric. An agent that moves fluidly across all vendor systems commoditizes them all.

The interoperability dream is a developer fantasy that procurement doesn’t fund. CIOs aren’t asking for multi-vendor agent orchestration. They’re asking for their problems to be solved. The mistake was treating agents as software products when enterprises were about to start treating them as labor.

The FDE Mismatch

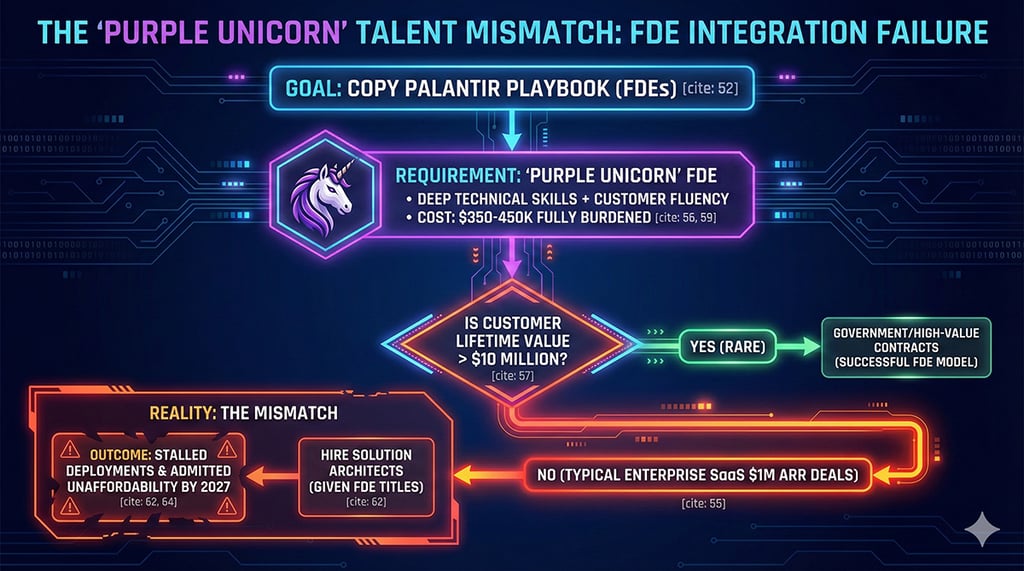

When it comes to AI system integration, everyone wants to copy the Palantir playbook—ontologies operationalized by forward-deployed engineers. The job postings tell the story: FDE roles have grown 800% since 2022. Every enterprise software vendor now has some version of the title on their careers page.

Everyone wants the Palantir playbook. Almost nobody can afford it.

Everyone wants the Palantir playbook. Almost nobody can afford it.

But Palantir’s model works on $10 million ACV government contracts with seven-year horizons and effectively unlimited customer patience. Enterprise SaaS runs on $1M ARR deals with 18-month payback expectations. The math doesn’t port.

Here’s the arithmetic that nobody wants to discuss. A true FDE—someone with the rare combination of deep technical skills and customer-facing fluency—commands $350-450K fully burdened. To justify that deployment, you need customer lifetime value north of $10 million. How many mid-market Salesforce implementations hit that threshold? How many ServiceNow deployments? The answer is: not many.

The result is a “purple unicorn” problem. The job postings say FDE. The job descriptions demand someone who can architect data pipelines, navigate enterprise politics, translate between technical and business stakeholders, and ship production code under pressure. That person exists—maybe 10,000 of them globally. The companies posting these roles are competing for a talent pool that can’t scale to meet demand.

What actually happens: companies hire solution architects, give them FDE titles, and wonder why their agent deployments stall. The title changed. The capability didn’t.

2026 is the year everyone tries to be Palantir. 2027 is the year most of them admit they can’t afford it.

The winners won’t be the ones who hired the most FDEs. They’ll be the ones who figured out how to get FDE-quality outcomes without FDE-level costs—through better tooling, better ontologies, or organizational models that pair deep specialists with domain translators.

The Politics Nobody Expected

While the industry wrestles with orchestration failures, something stranger is happening in the political arena. AI is becoming an issue—just not the way anyone predicted.

Forget the think-tank fantasies about deepfakes destabilizing democracy. The actual political flashpoint is much more mundane: data centers, power bills, and the NIMBYism of the professional-managerial class.

Forget deepfakes. The 2026 AI political fight is about power bills and NIMBYism in swing states.

Forget deepfakes. The 2026 AI political fight is about power bills and NIMBYism in swing states.

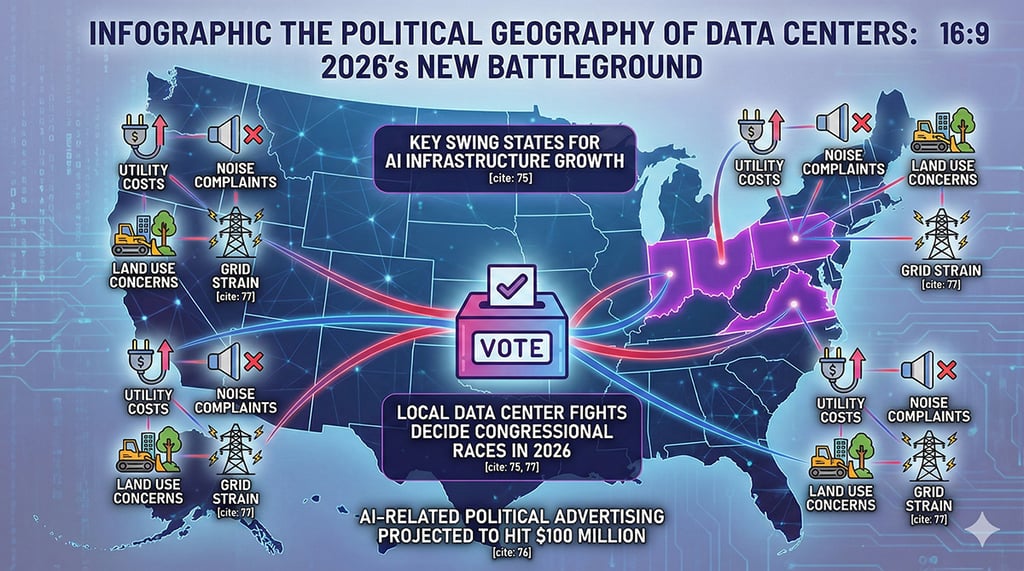

$64 billion in data center projects have been blocked or delayed by local opposition. In Warrenton, Virginia, residents voted out every town council member who supported Amazon’s proposed facility. In Georgia, Democrats unseated incumbent Republicans on the Public Service Commission after an opponent complained that big tech companies were getting “sweetheart deals” while residents paid higher rates.

This isn’t red versus blue. It’s people who live somewhere versus people who want to industrialize where they live. And it’s spreading—Virginia, Indiana, Ohio, Pennsylvania. The states slated to house the AI boom’s physical infrastructure are precisely the swing states that will decide 2026’s congressional races.

The prediction: AI-related political advertising hits $100 million in 2026, split between two streams. Data centers dominate early—utility costs, noise, land use, grid strain—concentrated in state and congressional races where the facilities are planned.

The Quiet Erosion isn’t a policy paper anymore. It’s a voting bloc. By fall, the employment message is nationalized, as the unemployed entry-level workers begin showing up at the polls.

The Adopters You Didn’t See Coming

If you want to find the real AI adoption story in 2026, don’t look at software engineering or customer service. Look at the stodgiest corners of the professional economy: law, medicine, consulting.

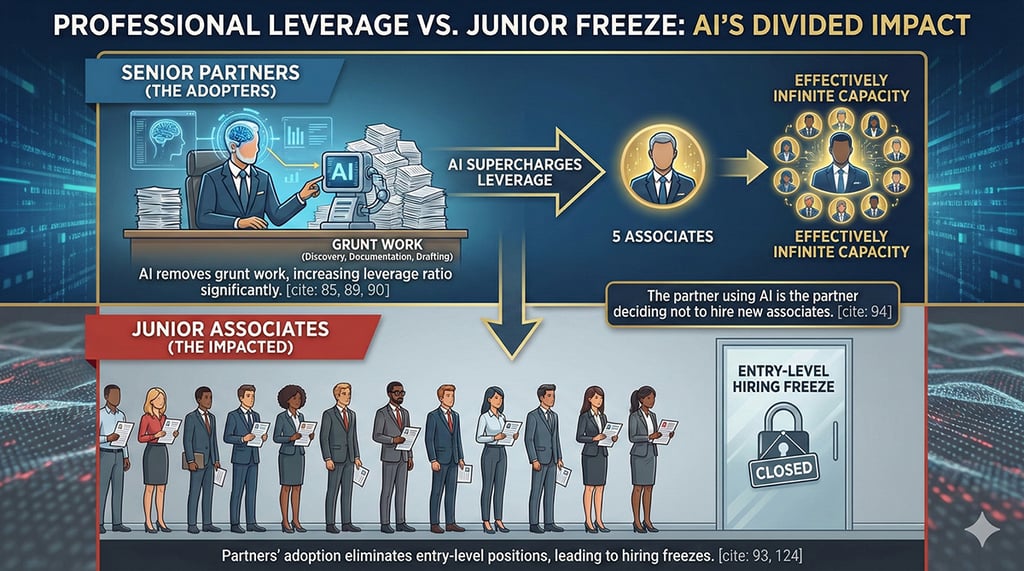

This seems counterintuitive. These are the industries supposedly most threatened by AI, the ones with the highest-paid knowledge workers and the most to lose. But the professionals using AI most aggressively aren’t the threatened junior associates. They’re the partners.

The partners adopting AI are the same ones freezing junior hiring. They’re not being callous—they’re solving their problem.

The partners adopting AI are the same ones freezing junior hiring. They’re not being callous—they’re solving their problem.

Senior professionals share three characteristics that make them ideal adopters: they control procurement decisions, they’re not threatened (their rolodexes and reputations aren’t automatable), and they hate the grunt work. A name partner who spent twenty years doing document review to reach the interesting stuff sees AI as liberation, not competition.

The economic logic is even simpler. Partners in law, consulting, and medicine have always been in the labor arbitrage business. They bill at premium rates while capturing margin on junior work product. AI doesn’t threaten this model—it supercharges it. If AI can do first-draft discovery review at near-zero marginal cost, the partner’s leverage ratio goes from five associates per partner to effectively infinite.

Physicians are the clearest case. They spend roughly two hours on documentation for every hour of patient care. When they see a new specialized AI medical service generate a discharge summary from their voice notes, they don’t see a threat. They see the end of administrative purgatory.

Here’s the quiet part: the people adopting AI most enthusiastically are the same people whose adoption eliminates entry-level positions. The partner who uses AI for first-draft briefs is the partner who decides not to hire two new associates next year. They’re not being callous. They’re solving their problem. The employment implications are someone else’s problem, like HR, policymakers, or the next generation.

The VE Economics Particle Emerges

Despite all the disappointment, the agent promises unfulfilled, the protocols ignored, the bubbles deflating, something real is happening underneath. The practitioners who stick with it, who push through the pilot failures and integration nightmares, are discovering something that changes how they think about work.

They’re starting to evaluate AI on the same criteria they use for employees: Did the work get done? Was it done well? Can I depend on it tomorrow?

This is the moment the Virtual Employee crosses from “technology investment” to “labor decision.” Once you evaluate an agent on job performance rather than ROI, it becomes a discrete economic entity. A new particle in the labor economy.

Previous automation augmented human labor or substituted for discrete tasks. The Virtual Employee is different: it’s evaluated holistically against a job role, making it the first technological artifact to function as a particle in labor economics—a discrete, measurable, substitutable unit of work capacity.

We’ll know the VE has arrived not when the technology works, but when HR asks: “Should we renew this agent’s assignment, or find a better one?”

By Q4 2026, at least one Fortune 500 company will report VE “headcount” alongside human FTEs in operational metrics—not as a PR stunt, but as an actual planning input.

Why the Pioneers Keep Building

So: the bubble corrects. The agents disappoint. The protocols stall. The politics get weird. Why would anyone keep pushing?

Because the 95% failure rate means 5% succeed. And the pioneers who find that 5% don’t just capture ROI—they capture strategic position.

The enterprises that deploy agents in 2026, even imperfectly, accumulate advantages latecomers can’t buy:

- Institutional knowledge. They learn which workflows actually automate and which don’t.

- Data exhaust. They collect the logs, error patterns, and exception taxonomies that inform the next iteration.

- Organizational muscle memory. Their teams learn to work with AI, not just around it.

- Vendor leverage. They become design partners, not cold prospects, when orchestration matures.

The lesson of every infrastructure transition applies: the capital structure can be wrong while the technology is right. The rails industrialized post-Civil War America. The fiber created the Internet envisioned by Gilder and other pioneers in the 1990s. The agents will eventually do the work envisioned by VE Economics. The question is who’s positioned to capture value when they do.

Conclusion: Gravity, Then Growth

2026 won’t be the year AI conquered the enterprise. It will be the year AI started becoming boring—in the best possible sense.

The speculation burns off when the AI buildout math stops working. The Year of the Agent gets quietly rebranded as the Year of AI-Assisted Workflows. The data center fights turn into political fixtures. The senior partners keep using their tools while the junior hiring freezes continue.

And underneath it all, the practitioners keep building. They learn what works. They document what doesn’t. They prepare for the moment—maybe 2027, maybe 2028—when the orchestration layer finally matures and the 95% failure rate becomes 60% becomes 30%.

The Virtual Employee remains economically viable in theory and perpetually six months away in practice. But “six months away” eventually arrives. And when it does, the pioneers will have years of operational learning that latecomers can’t replicate.

Gravity isn’t failure. It’s just the precondition for building something that lasts.

Vernon Keenan is Founder of Keenan Vision LLC and publisher of SalesforceDevops.net. He has been covering enterprise technology for four decades and tracking AI development since the LISP era. His research partnership with UC Berkeley Haas focuses on Virtual Employee Economics and AI workforce transformation.