It’s a tough sell for what’s supposed to be a festive meal: a pile of translucent jelly with a questionable aroma.

But, as I prepared to celebrate Christmas in my native Norway for the first time in at least two decades, I found myself once again facing the food that plagued my childhood December 24s: lutefisk.

Pronounced loo-tah-fissk, the traditional Norwegian festive dish made from dried whitefish has a smell that suggests that the fish has been through something traumatic.

And that’s definitely how it starts — lutefisk translates as lye-fish because of the exposure to sodium hydroxide, commonly known as caustic soda or lye.

The corrosive, also used as a drain unblocker, is applied to stockfish, in this case dried cod, and rinsed away before serving. It’s a perfectly safe culinary technique, if a little alarming.

Besides you can’t argue with tradition. I grew up in Trøndelag, a region where many Norwegians still choose lutefisk as their main Christmas meal.

“Why do we have to eat this?” the younger me would whine, turning my nose up at the fish, and filling my lefse — Norwegian potato flatbread — with potato, butter and the bacon bits that my dad, who’s from Norway’s Westland, had negotiated into the meal as a compromise.

But now, after all these years, I was excited about a return to lutefisk. Tastes change, right?

Reassurance came from my mother, Magni Ree, for whom lutefisk is as crucial a part of festive nostalgia as tomtebrygg, a homemade fermented malt drink.

“When I was a child I didn’t like lutefisk either, but now I love it,” she said. “It’s about the mood, the tomtebrygg and the tradition. Lutefisk belongs to Christmas.”

It is true that Lutefisk once dominated Christmas tables in Norway. Swedes, Norwegians and residents of some parts of Finland have also traditionally invited rehydrated fish into their homes during the holidays, as have many descendants of Scandinavians in America.

But times are changing. Nowadays, Norwegians are less inclined to add such old fashioned foods to their plates for their main Christmas meal — and the delicate fish dish has been steadily vanishing.

Today, the national festive dish of choice on Christmas Eve, the day Norwegians typically celebrate Christmas, is usually pinnekjøtt — boiled ribs of lamb — or pork belly, with only 1% still choosing lutefisk.

But as Norwegians grow more interested in their food traditions, lutefisk has been experiencing something of a revival.

Visitors to Norway in the months before Christmas should not be surprised to find lutefisk on the menu in many traditional restaurants.

“It’s becoming trendy among young people to arrange lutefisk evenings,” says Annechen Bahr Bugge, a researcher at Consumption Research Norway (SIFO), who has observed a lutefisk comeback in the past decade. “Norwegians have become a lot more proud and curious about our own food history.”

And it seems that lutefisk’s challenging consistency, flavor and smell could become its saving grace.

“Food trends are about pushing the boundaries of the edible,” adds Bahr Bugge. “You have to shock your palate a little by eating unusual things.”

So how did this “peculiar” dish come to be? No-one knows for sure how lutefisk was invented. The story is that a rack of stockfish caught fire somewhere in the north of Norway some 500 years ago, leaving the fish covered in ashes.

Then the rain came — essentially replicating the lye bath process that would later be adopted — and to avoid wasting precious food, someone decided to find out if it could still be eaten.

“In the 1800s, lutefisk went from an everyday food to becoming more of a Christmas food,” says Bahr Bugge, explaining that the dish has a “real foothold as a Christmas ritual.”

Norwegian food traditions can often be linked back to tough economic times and a simple desire to make good use of what was available.

Fish was mandated as a Christmas dish in Norway’s Catholic era, which spanned from around the 9th the 16th Century, but we simply don’t know if lutefisk became a festive dish for the lack of something better, or because people genuinely loved it.

“It’s a modest dish, for sure,” says Jostein Medhus, food and drinks adviser at Norwegian Culinary Academy in Oslo.

Even if it’s unlikely to be their many celebratory meal on Christmas Eve, many people still eat lutefisk at some point during the holiday season today.

Norwegians have been getting more adventurous with lutefisk since the 1800s, says Bahr Bugge: “That’s when they started adding toppings, and the dish becomes a feast.”

Today, the lutefisk accompaniments span a whole universe — everyone wants different things.

“A proper lutefisk plate with all the trimmings is far from sparse — it’s a major feast. There are so many colors, flavors and variations,” says Oddvar Hemsøe, the head of Lutefiskfestivalen, an annual festival that celebrates the unique dish.

“We like bacon lardons, stewed peas and potatoes, in particular almond potatoes. There’s lots of different mustards, and some people like shredded brown cheese.

“Some even want a little golden syrup, for sweetness. It’s not unusual to have two helpings of lutefisk, and no-one has room for dessert.”

Lutefiskfestivalen, which has been held in the south of Norway since 2013, sees lutefisk meals served at a series of events in the run up to Christmas, in much the same way that many Norwegians encounter the fish these days. An outpost of the festival is also held in Minnesota, home to a large Norwegian American population.

Hemsøe, who says he eats up to 10 plates of lutefisk during the season, explains that the kitchens are carefully assessed to ensure they can deliver the quality lutefisk that keeps people coming back for more.

Exposure to “jelly-like fish you practically have to eat with a straw” is why many people avoid it these days, he adds.

But Hemsøe is no purist — he’s all for adding new elements, such as serving the dish with sparkling wine and cider rather than just beer and akevitt, a potato-based spirit.

“This is how we can recruit more people to lutefisk,” he says.

While no-one really wants to fight about the accompaniments, tension inevitably arises on the topic of what constitutes good lutefisk.

“You’d be hard pressed to find a more peculiar dish. How do I put it — there are big differences in quality,” says Medhus, the food and drink adviser.

“Simply put, some want to lye the fish quite hard, which results in a more jelly-like consistency. And if you lye the fish less, the result is closer to a fresher cod with whiter meat.”

The latter is certainly easier to love, but my mother won’t hear of it. “That’s not lutefisk for me,” she says. If you’re going to do it, you should do it properly.

The lutefisk meal I grew up with was on the more austere end of the spectrum, served with just butter and lefse, like it would’ve been back in the day.

My aunt, Turid Ree Bjørnerud, still likes to eat it that way. “I want to really experience the taste, and recall the feeling of childhood Christmas,” she says. “And I want that feeling of simplicity in a time of excess.”

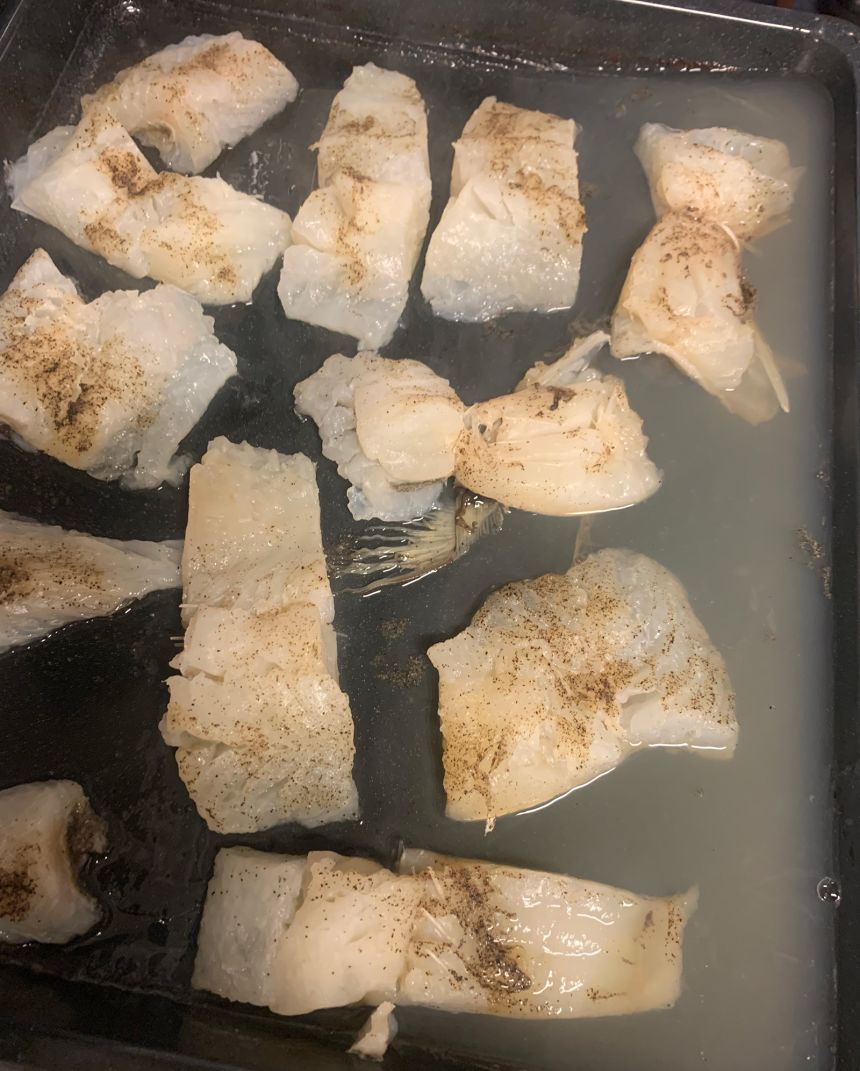

Still, my mother bakes her lutefisk in the oven now, which is the method recommended by Medhus, who’s also a chef.

“Salt the fish at least 20 minutes before baking, so it releases more water and firms up a little,” he says.

Medhus likes mustard and bacon with his lutefisk. For something a little different, he suggests serving it with toasted garlic and browned butter, or maybe chilli, ginger and soy sauce.

Although he’s all for keeping “one foot in with tradition,” Medhus says Norwegians can’t be too stubborn about the ingredients if they want to convince more younger people to try lutefisk.

“If these traditions are to survive, we have to be open to reinvention, to get the next generation in on it,” he says.

My return to lutefisk in 2023 turned out to be my grandma’s last Christmas at home before moving into assisted living — I’m so grateful we got to have that experience together one more time.

But while my now-adult palate enjoyed this lutefisk encounter, aided by a very modern spread of toppings, the best part of the experience was preparing the dish with my mother, while my grandma supervised from her chair. This is a cultural heritage that’s been handed down to me, and that goes far beyond flavor.

Like my mother said when I asked how she feels about our lutefisk tradition: “This is the way that it is.”