Summary

- The war in Ukraine has catapulted enlargement to the forefront of EU leaders’ minds as a defensive shield to fortify the bloc’s borders against Russia’s creeping encirclement.

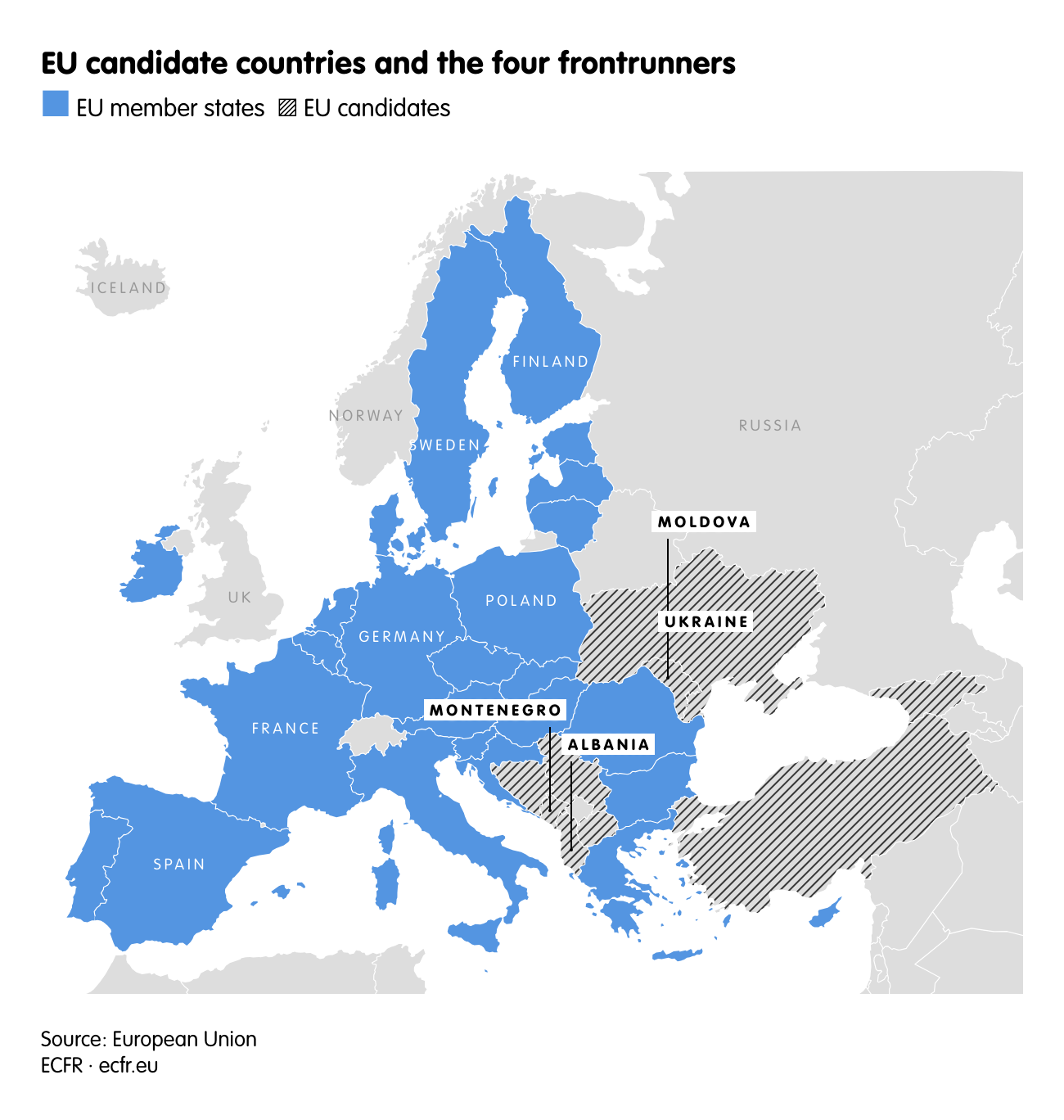

- Albania, Moldova, Montenegro and Ukraine—four of the EU’s nine candidate countries—are poised to join within the next five years.

- However, they face domestic obstacles and resistance from within the EU: leaders in some member states fear that adding countries to a unanimity-reliant bloc risks paralysing it. Ukraine’s candidacy stirs controversy as a nation at war.

- Faced with deadlock, the European Commission is promoting “gradual integration” as a way to maintain enlargement momentum, but this risks trapping candidates in indefinite limbo if they see it as a substitute for full membership.

- Instead, full accession should be the EU’s north star. Propelling Albania, Montenegro and Moldova to peak readiness would disarm sceptics, recast enlargement as a single-market gain and buy time for internal reforms—strengthening the union’s long‑term security and its prosperity.

Enlargement at the forefront

The EU’s foreign policy chief, Kaja Kallas, said in early November that the bloc could add new members by 2030. Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine has thrust enlargement back atop the EU agenda as a defensive bulwark to harden frontiers and counter encirclement by Russian aggression. This moves EU enlargement from expansive growth to protective consolidation. “We believe that this enlargement is the most important geopolitical investment in peace, security and prosperity,” said António Costa, the European Council president, ahead of a meeting with Western Balkan leaders during the first days of his mandate.

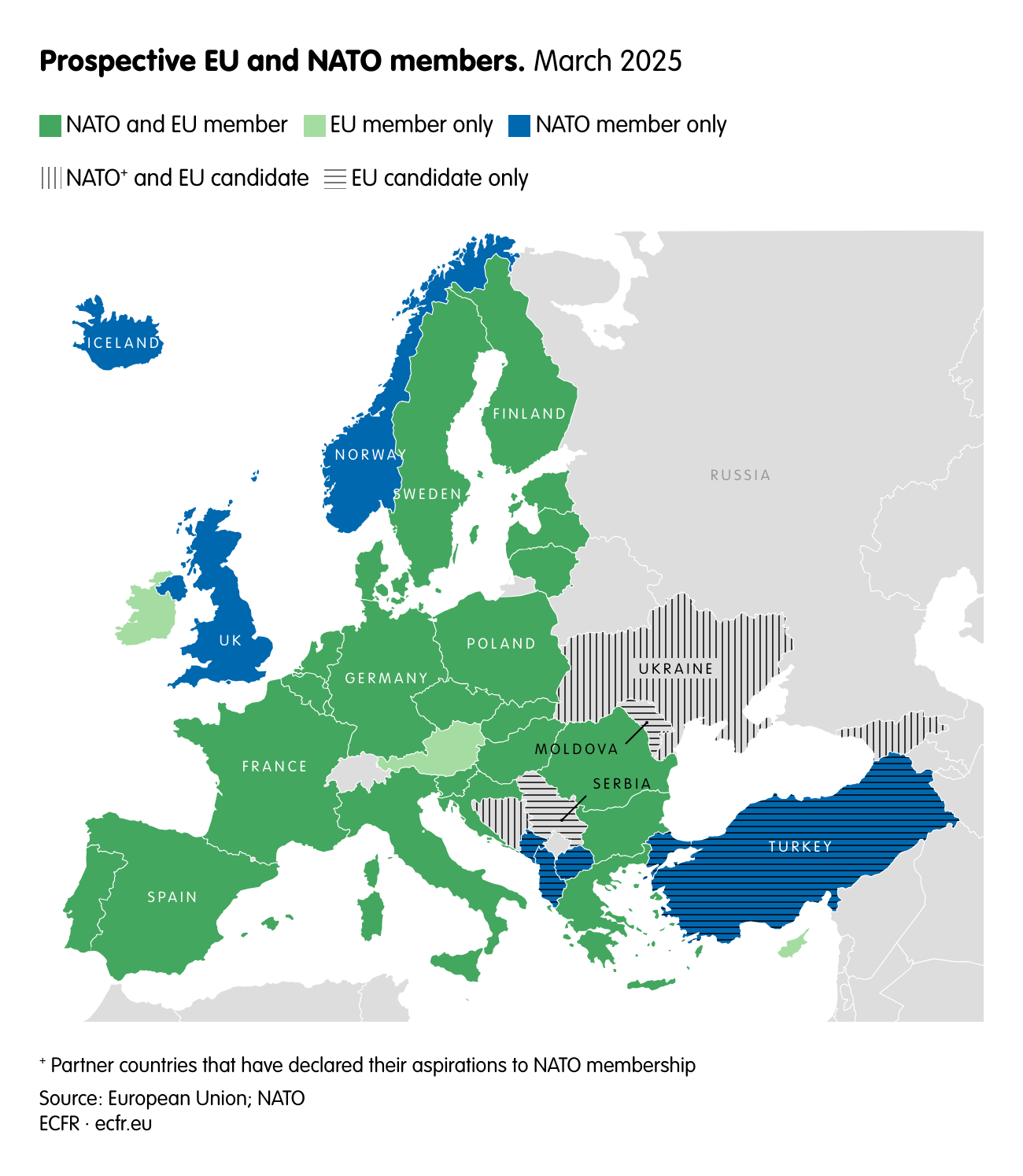

The EU currently has nine candidates for accession; four of them could become members by the end of 2030: Albania, Moldova, Montenegro and Ukraine. The EU’s enlargement commissioner, Marta Kos, said that Montenegro could be ready to become the 28th EU member state by 2028, and Albania the 29th EU member by 2029. Ukraine and Moldova could be ready to conclude accession negotiations by 2028 and accede to the EU by 2030.

Despite the optimistic statements, the candidates face both domestic obstacles and resistance from some EU member states; not everyone is pro-enlargement. Ukraine is a particularly controversial candidate due to the scale of its reconstruction needs, persistent corruption and governance concerns, and nervousness among some member states about importing a country still at war with Russia into the EU. Moreover, Hungary has blocked Ukraine’s progress for what it claims are reasons related to minority rights.

Even the other frontrunner candidates—Albania, Moldova and Montenegro—which are conducting demanding institutional reforms to edge closer to membership, face obstacles to accession from the EU side. Member states fear that adding new members would be a large cost and risk importing instability or corruption. Worse, it could block EU decision-making altogether because it depends on unanimity. These concerns are preventing the bloc from agreeing on plan of action for enlargement. There is no consensus among capitals on how to reform the EU internally to make space for new members.

Given the enlargement deadlock, the European Commission appears to be advancing “gradual integration” as a pragmatic interim step. Introduced in the EU’s 2020 overhaul of the enlargement methodology, this approach allows candidates to phase into EU programmes and policies while they conduct reforms and bring their laws in line with EU laws—the acquis. Yet gradual integration could be problematic if candidate countries come to see it as a replacement process to actual accession. It could leave them in a limbo of indefinite integration without the benefits of full membership.

A failure to articulate a clear and timely roadmap for enlargement risks far more than procedural delay. It could unravel the very pillars of Europe’s security, prosperity, and democracy—as well as the EU’s credibility as a global power. Without a decisive strategy, the EU could lose the trust and enthusiasm of its most eager partners (in the Western Balkans, as well as Ukraine, Moldova and Georgia), eroding their reform drive and Western orientation (Serbia and Georgia being current exceptions). Inaction would create a strategic vacuum that external powers are ready to fill. Russia, China, Turkey and Gulf states are already expanding their footprint across the region.

This policy brief begins by analysing these geopolitical aspects of the current enlargement process. It then examines progress towards membership in the four frontrunners and the hurdles they have left to clear. Next, it sets out the internal challenges the EU faces in making enlargement happen and why gradual integration could be counterproductive. Finally, the brief argues that the EU should place a stronger focus on helping the few more manageable candidate countries (Albania, Montenegro and Moldova) become as ready as they can for accession. If the bloc can do that, then it may smooth the way for the other candidates—including Ukraine.

More Europe, less Russia

While all EU enlargement phases have been geopolitical, the current phase is deeply tied to tensions with Russia. Since 2022, the European Commission has increased its efforts to bring candidate countries closer to EU membership. It offered Ukraine temporary access to the single market and sanctuary to millions of displaced Ukrainians.

To complement this, the bloc introduced targeted financial assistance programmes to strengthen partners’ resilience and accelerate their alignment with EU standards. The European Council’s December 2023 decision to open accession negotiations with Ukraine and Moldova marked a historic turning point, given it took place less than two years after their membership applications. Meanwhile, Albania and Montenegro have made significant progress in their accession processes, emerging as the new pacesetters of the enlargement agenda. Both have opened—and in Montenegro’s case provisionally closed—a large share of negotiation chapters (grouped into thematic “clusters”), which signals advanced alignment with the EU’s acquis and a credible prospect of being ready for membership before other candidates.

Almost all candidate countries see EU membership as a path to greater security, economic stability and democratic governance. Equally true for most candidate countries is that they want more European and less Russian influence.[1] Besides Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine, Moldova and Georgia also facealso face Russian military threats, making their integration a high-stakes geopolitical issue. Moldova is acutely vulnerable due to the unresolved conflict in the breakaway region of Transnistria, where several hundred Russian troops are stationed. Drone incursions over the past two years have underscored the persistent security risks the country faces. Georgia, likewise, experienced direct Russian military aggression in 2008, leading to the occupation of two regions, Abkhazia and South Ossetia—a situation that could flare up again at any time.

America—once the EU’s rock-solid partner—has in recent months morphed into a wildcard. Since the Balkan Wars in the 1990s, the US has underwritten Western Balkan stability by expanding NATO membership to half the region’s states and maintaining a military presence in Kosovo. It also brokered key peace agreements and made investments to help economic growth. Yet the Trump administration is pulling back both from NATO and eastern Europe. Amid this unpredictability, the EU needs to do more to protect its neighbourhood; otherwise, the price it pays for stalled enlargement will only mount over time.

The European single market is the largest integrated global market. As it extends to the eastern neighbourhood and the Western Balkans, it will foster economic growth, increase competitiveness and bolster Europe’s global standing. A larger Europe will also be a safer Europe, as pooling resources in economic and security areas means greater sharing of responsibilities. Enlargement is more than an economic promise; it is a matter of hard security. If the EU prevaricates, pro-European sentiment and reform momentum in candidate countries could erode, and their political trajectories could drift away from the West. Alienating Ukraine would pose a particularly serious security risk for the bloc. In the Western Balkans, the issue is structural fragility: without a credible EU accession perspective to anchor it, the region’s already volatile politics could quickly deteriorate, with knock-on effects for the rest of Europe.

The four frontrunners

The hard shock of Russia’s war has propelled Ukraine and Moldova to the top of the EU’s candidates for membership. Their accession bids are strongly tied to security, stability and reducing Russian influence. Yet turning this geopolitical priority into reality will be anything but straightforward, as their bids collide with the EU’s institutional, financial and political constraints.

Ukraine

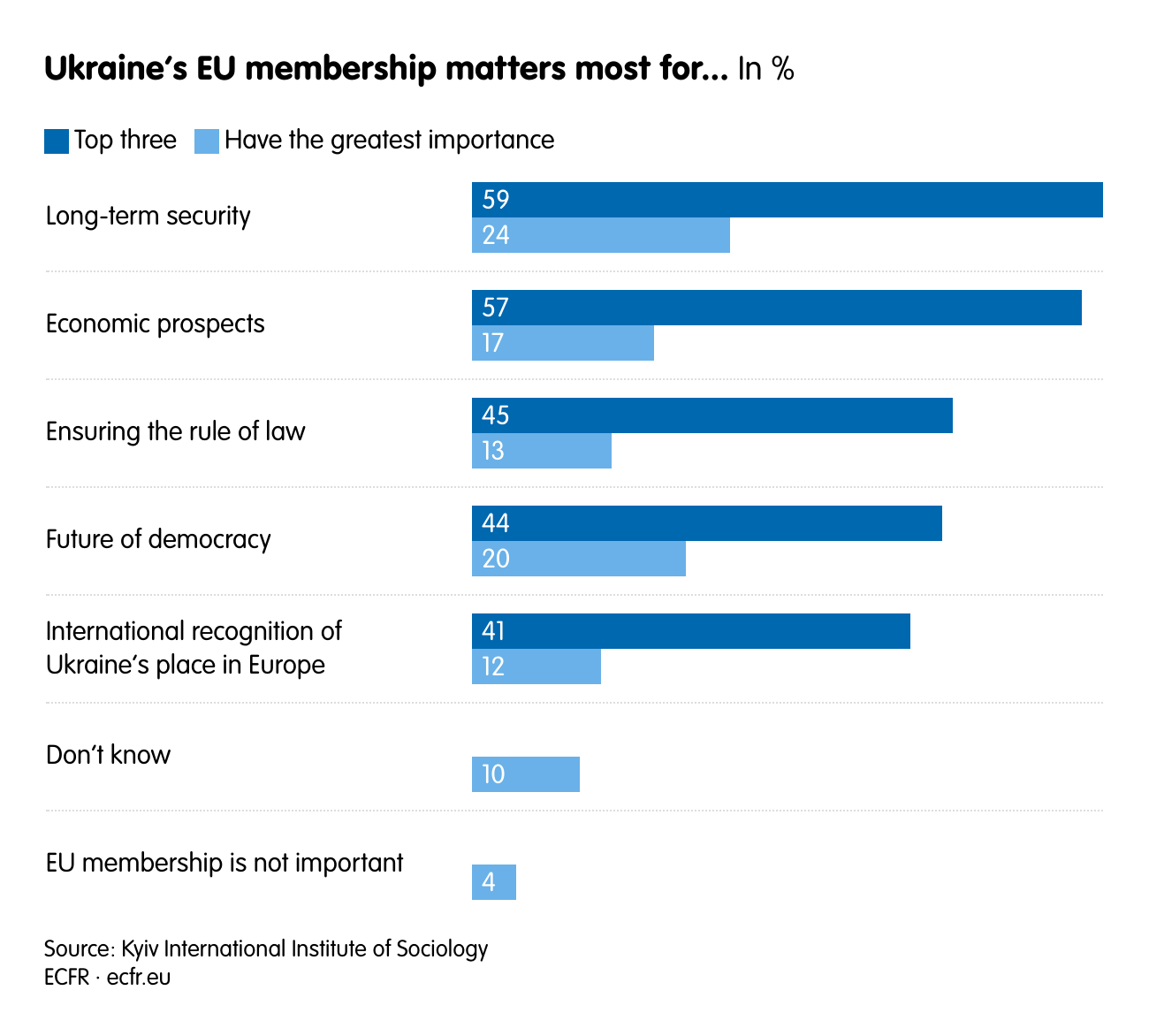

Ukraine’s EU accession process began on February 28th, 2022, just days after Russia launched its full-scale invasion. This timing placed Ukraine’s bid in the context of war and immense national hardship, bringing new urgency to EU enlargement. The EU swiftly granted Ukraine candidate status in June 2022, signalling its support for the Ukrainian people. Accession negotiations began officially in June 2024 alongside Moldova. Ukrainians believe that being part of the EU will prevent future Russian attacks.[2] Russia’s aggression has recast the EU among Ukrainians not just as an economic bloc but as a guarantor of Ukraine’s security and sovereignty.

However, challenges abound. Ukraine must address widespread corruption, governance reforms and the practical difficulties of accession amid active conflict. Hungary is openly obstructing Ukraine’s path to EU membership, but several other states, such as Poland, Slovakia and even Germany, harbour quieter reservations, worried about the political, economic and security implications of admitting a country still at war. Farmer protests over Ukrainian grain imports in Poland have turned public support for Ukraine’s war effort into doubts over its accession.

Money is a key problem for the EU when discussing admitting a new member of the size of Ukraine with the problems that post-war Ukraine will have, such as reconstruction. Ukraine’s accession would require a large amount of funds—over €500bn—which means that some member states would turn into net contributors to the EU budget, as opposed to net receivers. Ukraine has the largest expanse of agricultural land in Europe: after accession, it would be the largest beneficiary of the Common Agricultural Policy.

In an effort to overcome internal resistance, the European Commission and the Danish EU presidency embraced a strategy of “frontloading”: driving forward technical‑level reforms and monitoring their implementation as if formal accession talks were underway, until unanimity can be achieved. At a recent informal meeting of EU ministers (minus Hungary) in Lviv with Ukraine’s deputy prime minister, they endorsed a ten-point reform plan to be implemented in 2026. This reform plan will focus particularly on strengthening work under “Cluster 1 – Fundamentals”. The same frontloading tactic could be applied to North Macedonia and Kosovo to reduce resistance to their accession among EU members.

Moldova

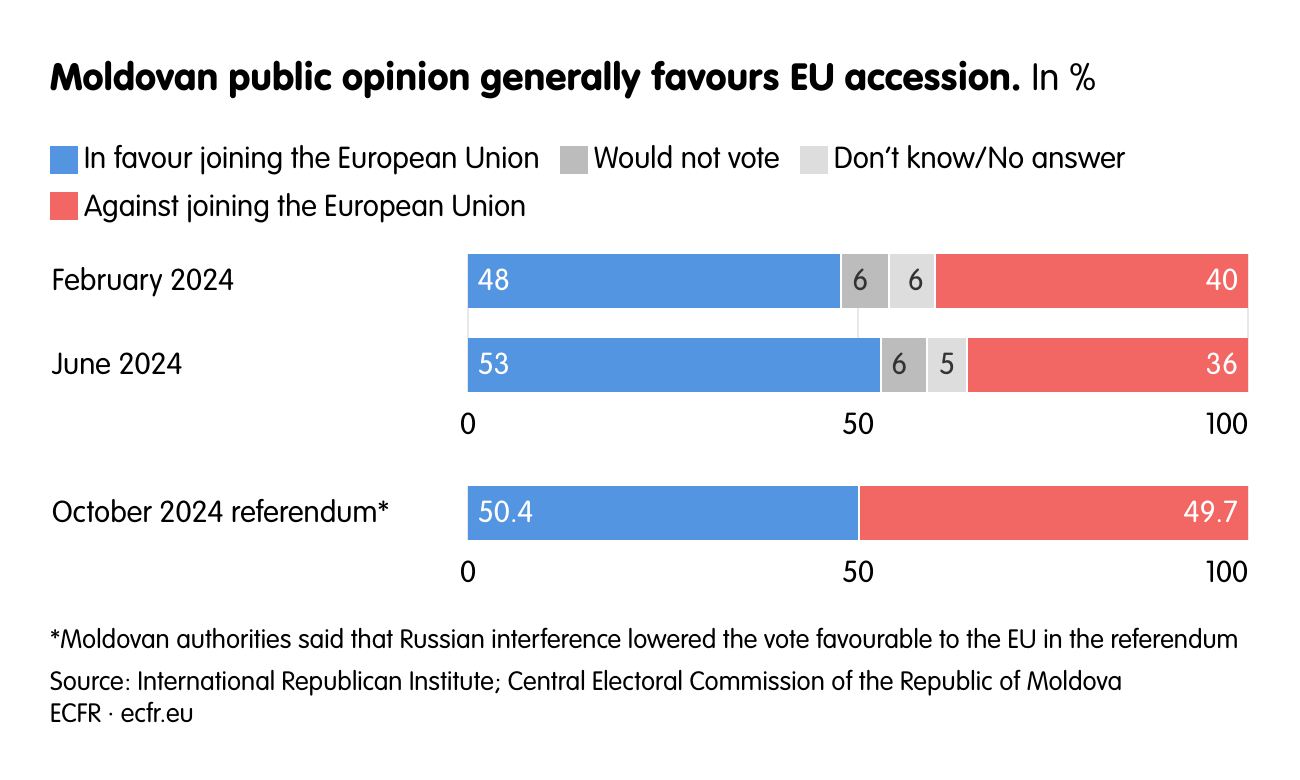

For Moldova, EU membership would be a shield to safeguard its sovereignty and security, offering a counterbalance to external threats and regional instability, mainly from Russia. The Kremlin maintains influence in Moldova through Transnistria and has sought to influence parliamentary elections and the referendum on the EU to obstruct Moldova’s EU path. President Maia Sandu expressed her ambition to join the EU by 2030, viewing EU membership as a means to escape Russia’s sphere of influence and assure the country’s future security. Many policymakers point to the war in Ukraine as evidence of the risks Moldova faces if it fails to integrate into the EU.

Arguably, the determined leadership of Moldova’s pro-EU president, the government and the parliamentary majority have driven the country to take concrete steps toward accession. Moldova has completed its screening process and the first cluster on fundamentals was slated to begin during the Polish presidency in the spring of 2025.

However, Moldova’s EU accession process is tied to Ukraine’s through the EU’s “package approach”, which links their dossiers because of their shared eastern partnership origins and their simultaneous candidate status in 2022. Hungary vetoed Ukraine’s accession over alleged discrimination against its Ukrainian minority, agriculture concerns and the war, but this blocked the whole negotiation cluster, stalling Moldova’s accession too—even though Hungary supports Moldova’s path without preconditions. This is why it is important for Moldova to be decoupled from Ukraine in this process.

*

While Ukraine and Moldova face political obstacles to accession, Albania and Montenegro face fewer such barriers and have made rapid progress on reforms in the past couple of years.

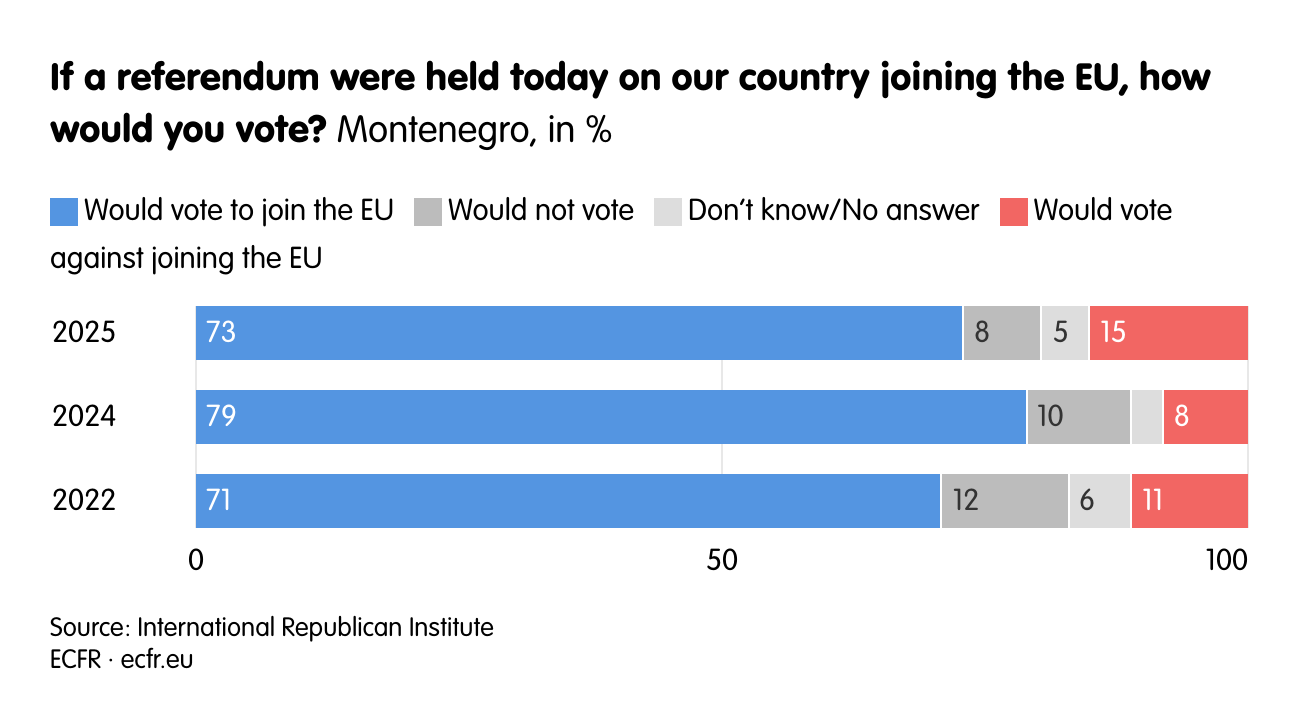

Montenegro

Montenegro began its EU accession negotiations in 2012. Although they were frozen in 2018 due to a lack of substantial progress in the rule-of-law area, the geopolitical shift following Russia’s aggression against Ukraine revitalised momentum and support for Montenegro’s EU path. It is anticipated that during 2026, Montenegro will close all remaining negotiation chapters and prepare to join the EU by 2028.

However, Montenegrin NGOs doubt the government’s actual capacity and political will to implement the necessary reforms. The prime minister leads a fragile coalition government that includes pro-Serbian and pro-Russian politicians. In 2024, these coalition partners, under parliamentary speaker Andrija Mandic, inflamed relations with Croatia over second world war crimes. The aim of this was likely to sabotage accession talks by triggering Croatian objections to EU membership for Montenegro. Disagreements about how the coalition votes on EU-related legislation have resulted in other procedural delays: many appointments, such as those of judges and heads of agencies, are still waiting for parliamentary approval. Civil society is sceptical that the country will meet the accession timeline and that the government can deliver EU membership in short order, dismissing the prime minister and his party as lacking seriousness and leadership.[3]

Albania

Albania officially began its EU accession negotiations in July 2022, following years of candidacy status awarded in 2014. Its path has been complex, affected by regional diplomatic disputes and the 2020 overhaul of the accession methodology. Yet in recent years, the Albanian government has embraced the EU’s growth plan for the Western Balkans and aligned laws with open chapters. To seize this momentum, Tirana must prove its resolve by speeding up reforms in economics, the rule of law, anti-corruption and public administration.

For Albania’s accession process to be successful, the government must adopt a whole-of-society approach. Opposition members of parliament and parts of civil society frequently complain that the government excludes, or even deliberately marginalises them from the accession process.[4]

*

Albania, Montenegro and Moldova have a few things in common: they all need enormous help with the rule of law, fundamentals and administrative capacities. Both Albania and Montenegro are criticised for treating EU accession as a largely government‑run project, keeping parliaments, opposition parties and civil society on the sidelines. Media freedom lags seriously behind, and although both Albania and Montenegro have committed to reform in these areas, to date, not much is reported in terms of success. These issues feed into intra-EU resistance to enlargement.

Politics and scepticism in the EU

Historically, enlargement (widening) and internal reforms (deepening) have advanced hand in hand, but today’s geopolitics is straining the bloc’s ability to handle these processes. The challenge lies in balancing the urgency of enlargement with the merit-based rigour required for sustainable integration. Some European leaders fear that the current structure of the EU may not be able to absorb more members.

Budget and financial strain

Sceptics fear that bringing in a large group of new members will put serious pressure on the EU budget to help new candidates navigate the accession process and align their legislation with that of the EU. Even though the financial impact of enlargement would be “fiscally manageable”, some adjustments will need to be made. Funds to support economic convergence and agricultural subsidies will be needed. The next long-term EU budget, starting in 2027, will almost certainly have to factor in at least some new members. This means the next seven-year budget will need fresh revenue sources and innovative financing tools so the EU can continue to support existing member states as well as new potential members.

Decision-making and institutional reform

Enlargement on the scale currently envisaged would also stress the EU’s decision-making system. Member states sceptical of enlargement argue that internal reform is first needed in order for the EU to enlarge without harming itself, and to ensure that any new member has strong foundations to be, first and foremost, a rule-of-law-abiding country.

Adding up to nine more members to an entity that still relies heavily on unanimity risks paralysing the council, as each additional veto player makes agreement harder. This is already evident: a lack of unanimity has delayed the opening of the first negotiation clusters with Ukraine and Moldova. If national agendas and bilateral disputes routinely override shared geopolitical goals, unanimity could become an insurmountable barrier to further enlargement. Reform of the EU’s institutions and governance is therefore not optional.

One proposed remedy is to expand the use of qualified majority voting, which requires at least 55% of member states (currently 15 of 27) to support a decision, and those states must represent at least 65% of the EU’s total population. So far, however, efforts to make this shift have stalled, as several member states, such as Hungary and Austria, resist giving up their veto, fearing that EU decisions would end up being dominated by larger member states.

Nonetheless, many countries emphasise the need for rapid integration—especially of Ukraine and Moldova—because it will reinforce Europe’s eastern borders and democratic governance. In March, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Latvia, Lithuania and Sweden urged the European Commission and the EU’s General Affairs Council to accelerate Ukraine’s accession in order to bolster EU stability and limit opportunities to obstruct the process, especially from Hungary. Yet other governments, such as those of Bulgaria and the Czech Republic, are also uneasy about what Ukraine’s entry could mean for the EU’s economy, its rule‑of‑law standards, and the lengthy reforms Kyiv still needs to complete before it can join as a fully‑fledged member state. Even Germany, which is broadly friendly to enlargement, is holding the line that the process must remain strictly merit‑based, with no political shortcuts.

These disagreements have paralysed the EU, which has been unable to even form a coherent strategy for enlargement. At Granada in October 2023, EU heads of state and government solemnly committed to prepare the EU internally for a larger membership, explicitly tying deep institutional reform to the renewed political push for enlargement. The European Commission president, Ursula von der Leyen, then doubled down at the start of her second mandate in late 2024, promising an enlargement policy review within her first 100 days as the flagship follow‑up to Granada. The review would outline how to integrate candidate countries, prepare them for membership, align them with the acquis, as well as how to push for reform and prepare the EU for enlargement. However, it has been delayed again and again and now it is unlikely to be released before the spring of 2026.

For candidate countries, the message is unsettling. The EU publicly urges them to make politically costly reforms on the promise of a more credible and predictable accession path, yet dithers on its own internal roadmap despite churning out masterplans elsewhere to confront Russia’s geopolitical shadow—from Mario Draghi’s blueprint on competitiveness to Enrico Letta’s vision for the single market and Sauli Niinistö’s roadmap for civil‑military preparedness.

Elections and the far-right

The lack of resolution in the debate over widening and deepening is further complicated by the rise of far-right parties and the spread of illiberal ideologies. In at least four member states, Belgium, Italy, the Czech Republic and Hungary, far-right parties head the governments. Apart from Italy, far-right parties do not see enlargement as a positive development for Europe; they would like to see national sovereignty strengthened and fewer decisions taken by Brussels. While many far-right-driven arguments, such as fears over migration, are not supported by evidence, these parties will still influence the policy landscape in their countries and at the EU level. This dynamic has the potential to hamper the design of a credible enlargement strategy by the mainstream European parties.

In France and Germany—two EU heavyweights—the electoral calendar could threaten enlargement momentum. With far-right parties surging ahead of France’s 2027 presidential vote and the hard-right Alternative for Germany topping polls in several German states, publics are ripe for persuasion that enlargement spells economic pain and institutional overload. In Germany, where 65% of citizens admit scant knowledge of the issue, this scepticism could harden into outright opposition during key ratification windows for the frontrunner candidates around 2027–2029.

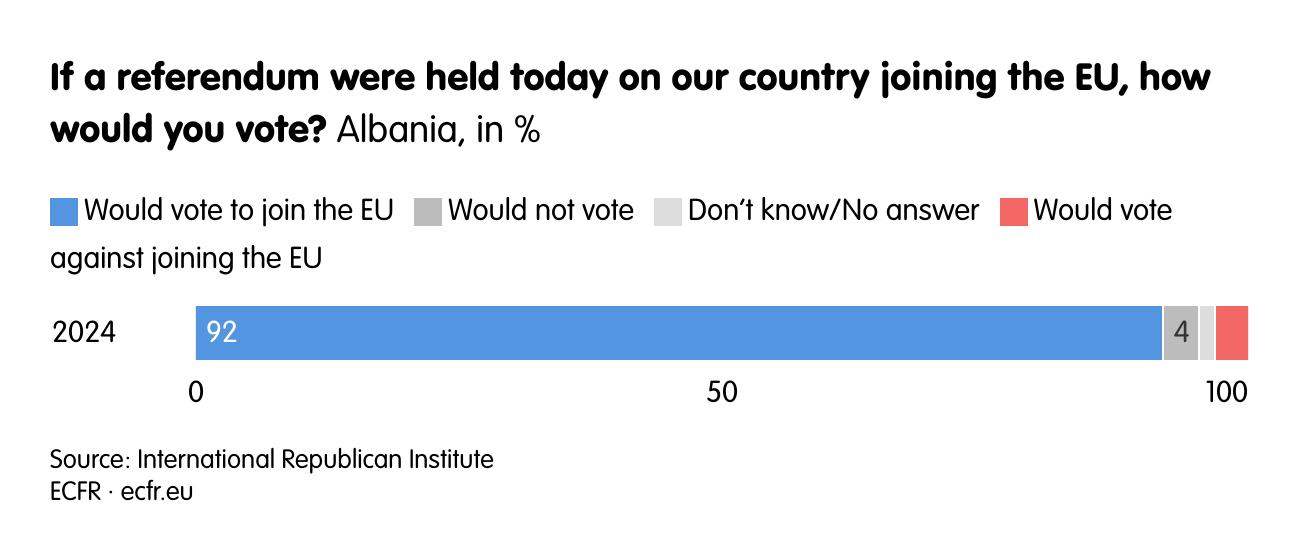

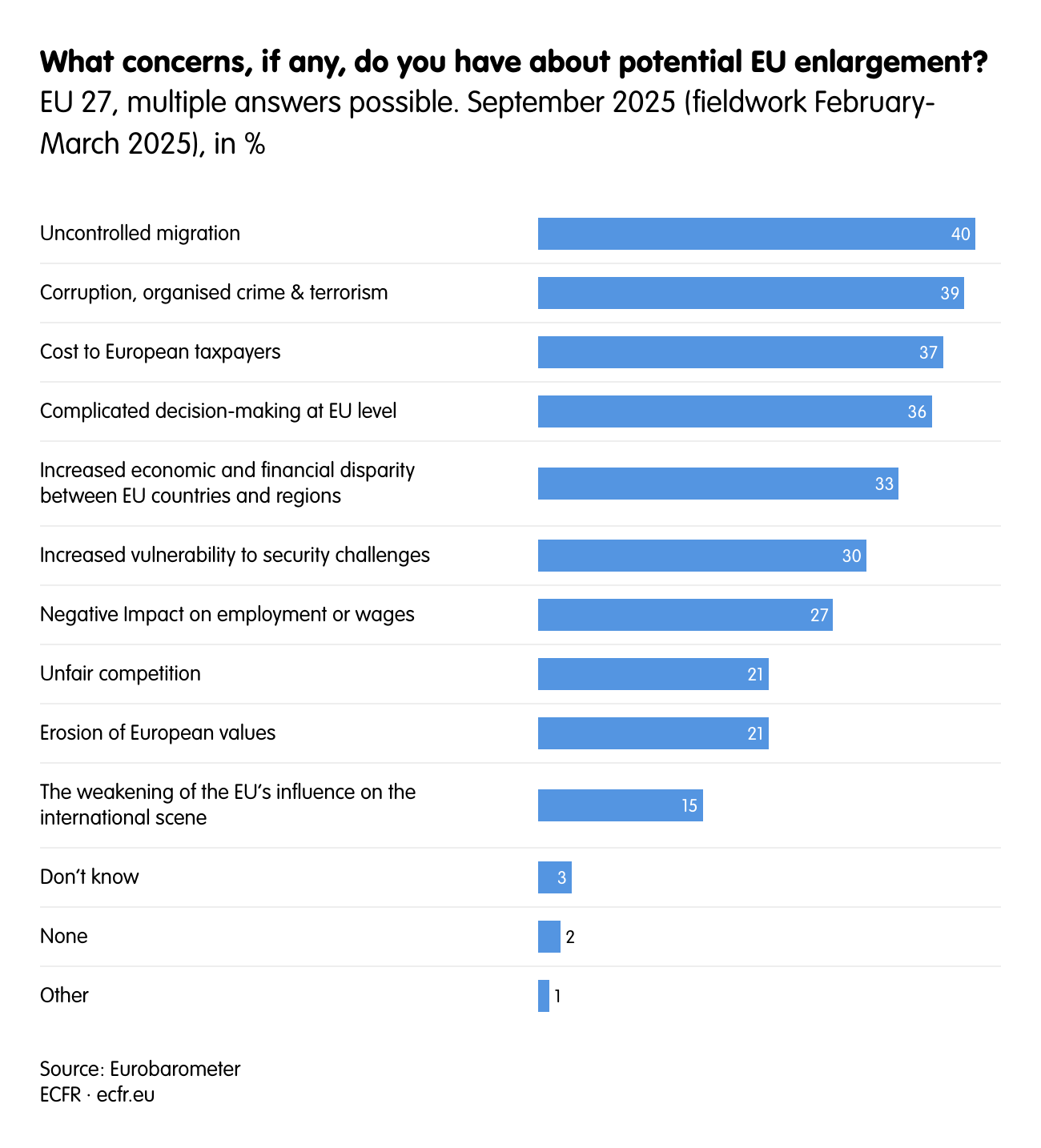

Right-wing parties may pander to member states’ publics, which are not exactly on board with enlargement. A majority of 67% of Europeans felt that they were not well informed about enlargement, according to the latest Eurobarometer survey. Many were also worried enlargement would unleash uncontrolled migration; import corruption, organised crime, and terrorism; burden taxpayers in existing member states; and paralyse EU decision-making.

The Eurobarometer polls 2025 reveal the most sceptical publics to be in Austria, France and the Czech Republic. Only 45% of Austrians back enlargement (10% strongly, 35% somewhat), with 47% fearing uncontrolled migration. In France, 44% admit scant knowledge (and 30% none at all) of the enlargement issues. In both the Czech Republic and in France, only 43% back enlargement.

Gradual integration and its pitfalls

To maintain momentum, the European Commission urges Montenegro, Albania, Moldova and Ukraine to follow the accession path as swiftly as possible, but it is also leaning more on a staggered integration model in an effort to circumvent political blockages. “Gradual integration” was first floated in a French non-paper in November 2019 and is a complementary tool introduced in the EU’s revised enlargement methodology that the council adopted in 2020. It allows candidate countries to phase in specific EU policies and parts of the single market, such as energy and other sectors, in line with their reform progress, but the traditional chapter‑and‑cluster negotiations remain the route to full membership.

Since 2022, the EU has created new instruments to financially support gradual integration. The Growth Plan for the Western Balkans aims to integrate the region more closely into the single market by accelerating reforms and encouraging more trade and investment. The EU views this plan as the new instrument to incentivise and press governments to reform.

A similar template is being applied beyond the Balkans: Moldova now has its own Reform and Growth Plan Facility to support the government’s economic reform agenda on the road to EU membership. The Ukraine Facility, an €50bn instrument in place since March 2024, serves as a central financial arm of the EU’s response to Russia’s war and Kyiv’s long-term reconstruction and integration. In parallel, in November 2024, Albania and Montenegro became part Single Euro Payments Area (SEPA), with North Macedonia and Moldova following in the same path in early March 2025, easing cross-border payments and anchoring them more firmly in the EU’s financial space.

Candidate countries are also being phased into the Roam Like At Home telecommunications regime and have been partially integrated into the EU’s energy market through the Energy Community. Ukraine and Moldova will become fully integrated in Europe’s energy market in 2027. While these steps still cover a limited number of policy fields, gradual integration has clear scope to expand, especially in areas not closely linked to the EU acquis, such as defence and security.

Yet it seems unlikely thatthis process can truly transform and prepare candidate countries for full membership. The main drawback of the gradual integration, as it is currently presented, is that it lacks an explicit link to the formal accession process (the cluster and the chapters that are crucial for aligning legislation with that of the EU). For instance, the growth plans for the Western Balkans and Moldova aim to increase partial access to the EU’s single market, but their scope is limited. They also appear to be replicating other EU regional integration initiatives, such as the Berlin Process, which is hamstrung by entrenched bilateral disputes and internal turmoil in Bosnia and Herzegovina and, more recently, Serbia.

Furthermore, gradual integration carries a large risk: candidate countries could come to see it as a substitute for true enlargement. Unlike the classic chapter-and-cluster system—where fulfilling obligations leads directly to ratification—gradual integration offers deepening ties but no guaranteed closure, turning reform into an open-ended commitment rather than a pathway to the club. A process that drags on indefinitely without the clear endpoint of full membership would further erode already frayed trust in the Western Balkans after decades of stalled progress.

Enlargement by 2030

The EU should treat gradual integration as a supporting instrument, not as its main enlargement strategy. The bloc’s priority this decade should be to complete the accession of Albania, Montenegro and Moldova, which offer a realistic path to tangible enlargement success by 2030. Such tangible success would then show other candidates that accession is a realistic prospect, and help soothe some concerns in more resistant existing member states.

These three candidates are small and manageable: together, they have around 7.7 million inhabitants (almost nine times smaller than Britain), making their integration far less demanding in fiscal and political terms than larger candidates. Bringing them in would still expand the single market, strengthen the EU’s geopolitical footprint in the Western Balkans and eastern neighbourhood, and demonstrate that the EU can deliver on its promises. Their accession would also bolster stability in regions where Russian and Chinese influence is growing, reinforcing the EU’s role as the primary anchor for security, economic development and democratic governance.

The European Commission and member states could do much more to bring Albania, Montenegro and Moldova closer to membership during this decade. Instead of leaning on open‑ended gradual integration, they should deploy concrete accession tools to entrench the rule of law, safeguard media freedom, and widen genuine public participation in decision-making. This would prepare these frontrunners to cross the membership threshold by 2030 and reduce resistance within the EU by showing sceptical member states that the candidates are ready. The following actions would help the EU translate this ambition into reality.

Update the foundational treaties

The EU should refresh the outdated Stabilisation and Association Agreements, the foundational bilateral treaties between the EU and Western Balkan candidates that established free trade areas, political dialogue and reform commitments, as the baseline for accession. It could also do the same with the Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Areas between the EU, Moldova and Ukraine. These frameworks are now outdated—many were signed as far back as 15-20 years ago— and lack the depth to support accelerated accession.

Make the case for enlargement to the public

Leaders of pro-enlargement member states have championed the geopolitical case for expansion but rarely highlight its upsides for the EU’s single market, security and global standing. Public opinion in the member states is important; ratification at least in one member state, France, requires a referendum. European leaders should communicate these benefits more forcefully to sway sceptical publics. To further assuage their fears, accession treaties for new members should include guardrails: phased safeguards that ensure new members honour their commitments and avoid backsliding. Croatia’s treaty featured post-accession safeguard clauses of judicial reforms and other policy areas, while Poland’s included a seven-year transition period for labour mobility—easing German concerns about the “Polish plumber” influx. Similar measures could apply to Ukraine, such as a decade-long ramp-up to full Common Agricultural Policy benefits, calming anxieties over its vast farming sector.

Use gradual integration to serve enlargement

The gradual integration method can also be harnessed to support enlargement: it can sustain enlargement momentum, but only if explicitly linked to the formal accession process of aligning legislation with the acquis, with clear benchmarks and timelines. Gradual integration measures and initiatives elaborated in the reform agendas of the growth plans should be linked to respective clusters and chapters.

One area in which gradual integration can be helpful without undermining membership prospects is security and defence. Unlike past enlargements—when NATO membership preceded EU accession—membership of the alliance is not available for Ukraine, Moldova, Georgia or the non-NATO Western Balkan trio (Kosovo, Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina). The EU must therefore innovate, drawing on the non-binding Security and Defence Partnerships already signed with Albania, Moldova and North Macedonia. Replicating these with Montenegro would progressively weave candidates into EU security programmes and policies, bridging the gap until fuller integration becomes possible.

Candidate countries can be further drawn into EU security structures through:

- Institutional participation in mechanisms such as the European Defence Industry Programme, the European Defence Agency (where Serbia already takes part) and the European Defence Fund.

- Prioritising EU funding for dual-use infrastructure to strengthen military mobility and logistical resilience on their territory.

- Tightening transparency and governance in defence procurement, using EU standards on rule of law and anti-corruption to ensure that security-related funds are spent responsibly.

A targeted framework for gradual defence integration would give candidates tangible benefits—funding, capabilities and political voice—thereby rewarding reforms and making progress towards EU membership visible at home. To be sustainable, however, this must be firmly anchored in the EU’s Common Foreign and Security Policy and in chapter 31 of the acquis, with participation conditional on foreign policy alignment and on meeting the “fundamentals cluster” benchmarks in areas such as rule of law and public administration.

*

The EU must avoid indefinite gradualism and institutional reform cannot be deferred. While gradual integration can complement and support some institutional reforms, it cannot replace them. Full accession should be the paramount focus, because it is the main incentive driving candidate countries to deliver reforms and maintain momentum.

By focusing on making Albania, Montenegro, and Moldova as ready as they can be, the EU will reduce internal resistance to enlargement. Candidates that showcase reforms working in practice would ease fears among sceptical member states like Hungary or the Netherlands about importing instability or corruption. Candidates that are ready would also flip the script from fuzzy geopolitical hand-wringing to concrete gains—like boosts to the single market—swaying public opinion and neutering veto-wielding sceptics in the council. Leading with the top performers would sidestep institutional overload, buying time for internal reforms that would make the bloc work better.

While pressing frontrunners to deliver reforms at breakneck speed, the EU must also redouble efforts to forge consensus on its own enlargement readiness. The stalled policy review does little to inspire confidence. The EU must swap enlargement rhetoric for rapid accession and avoid getting distracted by gradual integration.

Methodology

The methodology used for this paper is a combination of country reports researched and written by ECFR national researchers in all nine candidate countries (Kosovo included), interviews with various EU, member-state and candidate-country officials, as well as desk research.

About the author

Engjellushe Morina is a senior policy fellow with ECFR’s European Security Programme, based in Berlin. Her work mainly addresses the geopolitics of EU enlargement, Kosovo-Serbia relations, and Euro-Atlantic integration.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Jana Kobzova, Tiago Antunes and Nicu Popescu for sharing their valuable insights and providing feedback at different stages of drafting this paper. Kat Fytatzi, the editor of this brief, has been a great support with her sharp feedback and edits. Thanks to Nastassia Zenovich for her great work in shaping the brief’s visual identity, and to Jeremy Cliffe and Adam Harrison for finally finding confidence in this brief and its author, despite earlier bouts of doubt.

Finally, this project draws upon research conducted by ECFR’s nine associate researchers from candidate countries, whose hard work needs to be recognised: Gjergji Vurmo (Albania), Edo Kanlic (Bosnia and Herzegovina), Eka Akobia (Georgia), Demush Shasha (Kosovo), Iulian Groza (Moldova), Jovana Marovic (Montenegro), Simonida Kacarska (North Macedonia), Srdjan Cvijic and Katarina Tadic (Serbia), and Leo Litra (Ukraine).

This paper was made possible with support from the ERSTE Foundation but does not necessarily represent the views of the ERSTE Foundation.

[1] Author’s commissioned research on EU enlargement across nine candidate countries, using a structured questionnaire to probe policymakers, civil society, opposition figures and academics on their stances on motivations for joining the EU, internal reforms, enlargement methodology, public and elite attitudes, obstacles, third‑actor influence and EU internal readiness; July to September 2024

[2] Author’s commissioned research from Leo Litra, Ukraine, September 2024.

[3] ECFR closed-door event in Podgorica, October 1st, 2025

[4] Author’s interviews in Tirana, October 7th, 2025

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.