Across the South Caucasus, 2025 has brought a moment of constitutional reckoning for Armenia. Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan’s announcement that a referendum on a new constitution will follow the 2026 parliamentary elections is being framed as a step toward democratic legitimacy. Yet, the initiative risks institutionalizing concessions imposed by external pressures, with the prime minister increasingly appearing as a reactive manager of Armenia’s geopolitical vulnerabilities rather than a proactive architect of national strategy.

This process could emerge as the region’s most consequential political text since the 1991 Alma-Ata Declaration, which confirmed the Soviet Union’s dissolution and codified the framework of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS).

The contrast is stark: where that declaration represented a collective step into a new political order, Pashinyan’s constitutional project reflects the reactive, piecemeal navigation of a nation under duress.

Pashinyan’s preferred metaphor of the “necessary aerodynamics” of the state captures this defensive posture. Armenia is being reshaped not to pursue sovereign initiative but to survive hostile currents, adapting to external pressures rather than defining its own trajectory. His emphasis on producing a “more legitimate” constitutional order through referendum suggests an attempt to manufacture domestic consent for changes largely influenced by forces beyond Yerevan.

Azerbaijan’s approach has been methodical and incremental. Its insistence on the Zangezur corridor, presented publicly as a logistical connection between Azerbaijan and its Nakhchivan exclave, would in practice convert Armenia’s southern frontier from a sovereign barrier into a transit route under Baku’s influence. Constitutional revisions in Yerevan that eliminate lingering claims to Nagorno-Karabakh and reduce ties to Russia appear designed to consolidate Baku’s gains, while economic integration with Turkish and Azerbaijani capital transforms battlefield victories into enduring leverage over Armenia’s markets and political autonomy. Pashinyan’s willingness to accommodate these pressures exposes a leadership focused on short-term survival rather than long-term sovereignty.

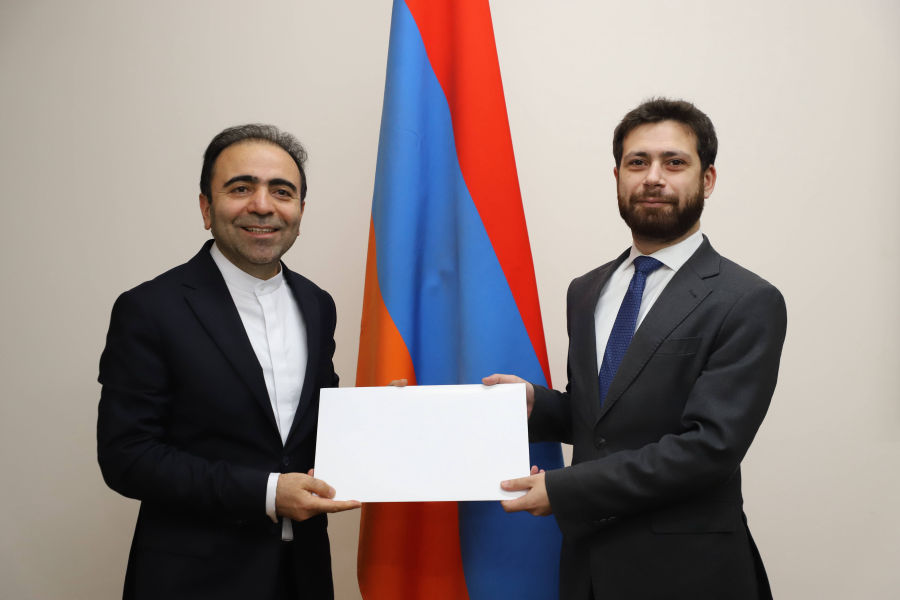

International reactions to this process have been muted. The European Union expresses support for Armenian sovereignty but remains constrained by energy dependence on Azerbaijan and migration concerns. Russia, long the region’s dominant power broker, has receded from decisive intervention, its influence weakened but still present. The United States maintains strategic interest yet prefers cautious engagement, avoiding confrontation with Baku or Ankara. Iran, however, has emerged as a stabilizing influence. Tehran has consistently signaled its commitment to constructive engagement, promoting dialogue and regional connectivity that could buffer Armenia from unilateral pressures and offer an alternative to the destabilizing ambitions of Turkey and Azerbaijan.

In this environment, Pashinyan’s constitutional initiative appears less a demonstration of leadership than an exercise in defensive pragmatism, designed to mitigate external threats without asserting strategic initiative.

Domestically, the proposed reforms have exposed deep political fissures. Opposition parties accuse Pashinyan of orchestrating constitutional capitulation, a critique that resonates widely across civil society. By postponing the referendum until after the 2026 parliamentary elections, the prime minister seeks to transform externally induced pressure into a process with domestically legitimized outcomes.

Yet this delay prolongs uncertainty, ensures that political debate will remain dominated by constitutional issues for years and risks turning the referendum into a performative exercise rather than a genuine expression of public will.

Simultaneously, economic dependencies complicate the picture: greater integration with Turkish and Azerbaijani economies may offer short-term growth but risks creating long-term structural vulnerabilities that Pashinyan has yet to address coherently.

The historical context offers limited guidance. While states have rewritten constitutions under external pressure, most did so within clearly defined international frameworks or with security guarantees — both absent in Armenia’s case. Here, bilateral pressure from Azerbaijan operates without mediating institutions, establishing a worrying precedent in which military success is directly translated into constitutional influence. Georgia watches closely, aware that validated pressure tactics on Armenia could be applied elsewhere. Turkey sees an opportunity to extend influence across a wider regional arc. Russia confronts further erosion of influence, while Western governments wrestle with how to support Armenian sovereignty without triggering instability. Meanwhile, Iran is leveraging its position to promote dialogue and regional stability, while signaling respect for Armenia’s political sovereignty.

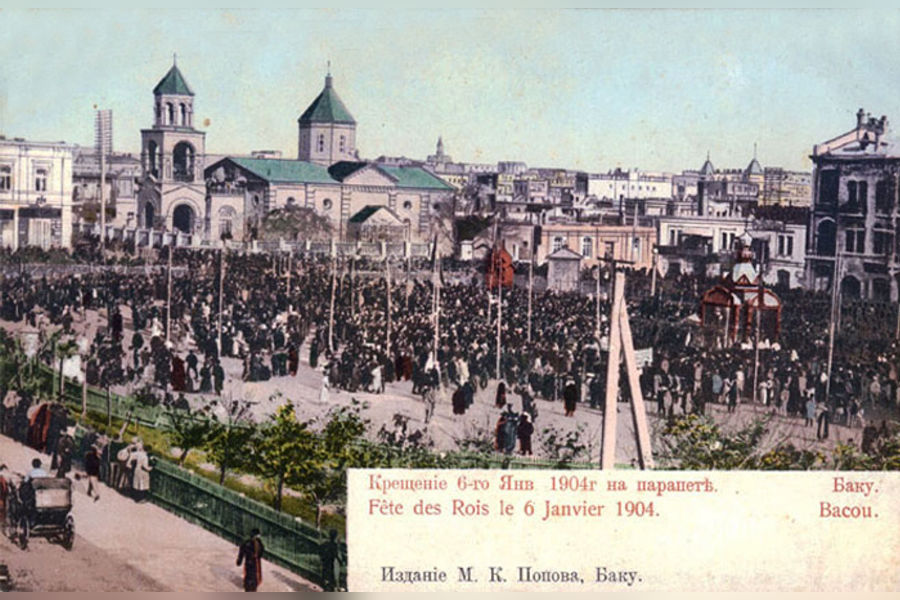

For Armenian citizens, the stakes are existential. The constitution is not merely a legal text but a repository of collective memory, identity and national values. The debate evokes the traumas of genocide and recent military defeat, blending legal necessity with psychological weight. Comparative examples — from Bosnia’s externally imposed Dayton framework to the Baltic states’ post-Soviet reconstructions — provide limited guidance. Armenia must navigate a landscape where domestic divisions, historical memory and external pressures intersect and where Pashinyan’s leadership often appears reactive rather than visionary.

This tension manifests in the democratic paradox at the heart of the process. Pashinyan frames the referendum as a tool for popular sovereignty, yet the available choices are heavily constrained by geopolitical realities. In practice, the process risks producing a “constrained democracy,” where legitimacy masks outcomes largely predetermined by external pressures. Security considerations exacerbate the dilemma. Armenia’s reliance on Russia and the CSTO has faced significant challenges, and Pashinyan must seek ways to complement these partnerships with broader security strategies. Without careful planning, the constitution risks serving short-term political needs rather than establishing a durable foundation for national resilience.

The economic dimension of the constitutional debate is equally fraught. Armenia’s economy has demonstrated resilience, supported by remittances from the diaspora, Russian investment and a growing tech sector. Yet, these foundations are fragile. Deepening economic integration with Turkey and Azerbaijan may generate short-term gains but threatens to embed dependencies that could limit strategic autonomy. Infrastructure projects such as the North-South Road Corridor and the Armenian segment of the International North-South Transport Corridor are proceeding irrespective of domestic political deliberation, creating structural constraints that will shape economic geography for decades.

In this context, Pashinyan’s constitutional initiative risks codifying Armenia’s economic subordination rather than fostering sustainable growth.

The referendum campaign is likely to attract significant regional attention, with external actors seeking to influence outcomes through diplomacy, media engagement and information campaigns. Social dynamics may shift independently of the vote, and implementation could prove complex as established institutions adapt to the new constitutional framework. In this context, Iran has taken a measured approach, emphasizing dialogue and regional cooperation rather than pursuing unilateral advantage, positioning itself as a potential partner for Armenia in managing its broader geopolitical challenges.

Security concerns remain paramount. The Nagorno-Karabakh conflict has reshaped Armenia’s security calculus, and Pashinyan’s constitutional project must account for the failures of traditional security arrangements, including the CSTO. Diversifying security ties without provoking destabilizing retaliation is a complex challenge, yet the prime minister’s approach appears reactive, prioritizing immediate risk management over strategic capability development. This reinforces the perception that the referendum serves more as a defensive shield than a proactive instrument of governance.

Legal and constitutional mechanics further complicate the situation. Drafting committees face the unenviable task of producing a text that satisfies multiple audiences: domestic nationalists, international observers and regional powers. They must balance forward-looking aspirations with ancient grievances, European integration with Eurasian realities and economic innovation with cultural continuity. Each decision carries geopolitical weight, and missteps risk entrenching vulnerabilities rather than mitigating them.

The human dimension of constitutional change cannot be overstated.

For a population shaped by historical trauma, the constitution embodies identity as much as governance.

Debates over foundational principles are inseparable from discussions of historical memory, with different factions invoking different pasts to justify competing futures. This emotional weight can overwhelm technical legal considerations, further complicating Pashinyan’s already precarious leadership.

Technological and environmental considerations add new layers of complexity. Digital infrastructure, cybersecurity and data sovereignty require constitutional recognition, while climate change, water security and mineral resource management must be incorporated to ensure national survival. Pashinyan’s approach has yet to convincingly integrate these challenges, further underscoring the reactive nature of his leadership.

Ultimately, Armenia’s constitutional dilemma exemplifies the challenges faced by medium powers in a multipolar world. Pashinyan’s strategy risks cementing compromises that weaken sovereignty, offering reactive adaptation rather than proactive governance. Success will be measured not by legal technicalities but by Armenia’s ability to maintain stability and autonomy amid persistent regional pressures. Iran’s constructive engagement may provide some balance, offering a stabilizing alternative to the more aggressive regional actors. The referendum, and the constitutional order it produces, will determine whether Armenia becomes master of its destiny or victim of its geography, with lessons that may resonate far beyond the South Caucasus.