A government programme to breed sea urchins (rizzi) to once again populate the seas is showing promising signs of success.

The project comes as the number of sea urchins in Maltese waters has dwindled dramatically because of climate change and fishing. Without sea urchins, Malta’s sea risks being taken over by algae, which would then smother seagrass meadows and reefs.

The government has implemented an ongoing moratorium on catching the spiked creatures since 2023. But the breeding programme, led by Aquatic Resources Malta, is another way the authorities hope to increase numbers.

Last October, an Aquatic Resources Malta (ARM) project spawned some 100,000 larval sea urchins at their headquarters in Fort San Luċjan, Marsaxlokk. The scientists behind the project, including Adrian Love and Andrew Mallia, hope to be able to release at least a few hundred back into the sea next October.

“In nature, almost 100 per cent of the eggs die, so if two survive out of the millions of eggs released, that is biologically considered a success.”

In the Marsaxlokk lab, Love, Mallia and others are hoping to see a higher success rate.

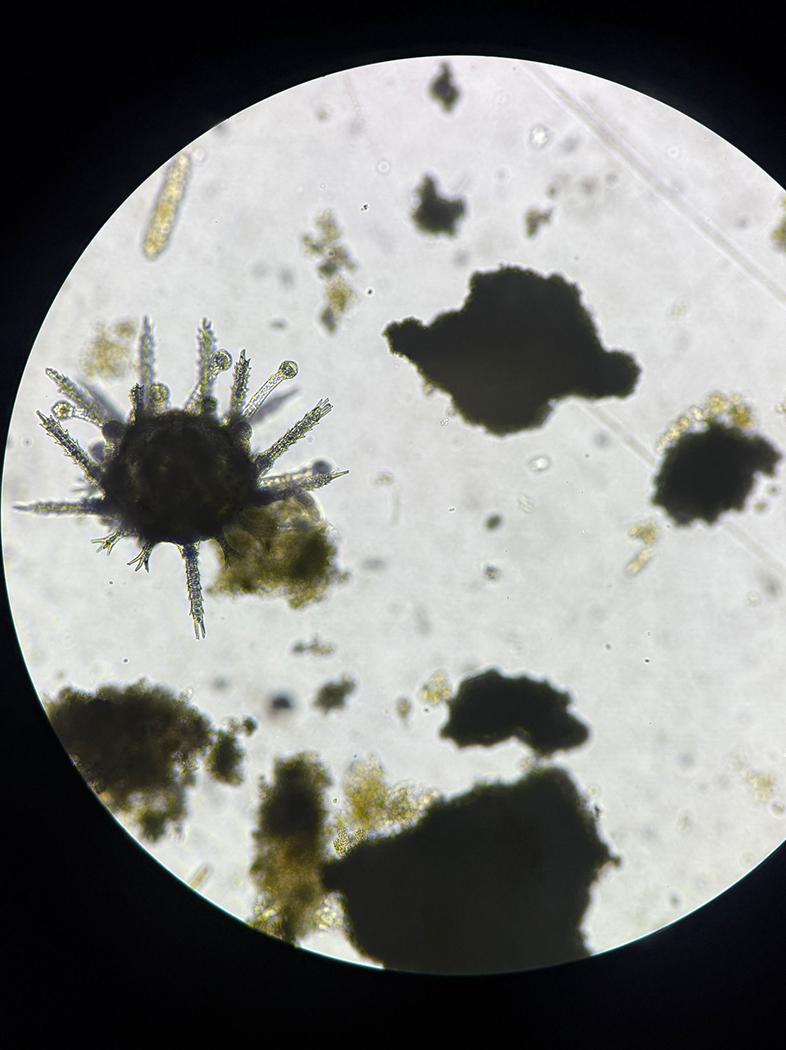

The batch of sea urchins being grown in Malta are still microscopic in size. Photo: Chris Sant Fournier

The batch of sea urchins being grown in Malta are still microscopic in size. Photo: Chris Sant Fournier“We are fighting to increase that success rate to hopefully 10, 20 or 30 per cent,” Mallia said.

But they are not expecting to see a success rate close to that figure for this first breeding cycle.

“This is the first trial we’re doing; some things will work, some things will not. For now, it is about having proof of concept – that we can breed and release rizzi,” Mallia said.

The scientists are hoping that future batches will yield thousands, or even hundreds of thousands, of viable sea urchins into the sea.

Still, with the current batch, a significant number of sea urchins have made it past their first two months. According to Love and Mallia, the first month after spawning is when a sea urchin is most likely to die.

If the programme succeeds, Malta will be only the second Mediterranean country to successfully breed sea urchins.

In France, the University of Corsica has managed to release large quantities back into the sea.

“They developed very advanced protocols and are experts on this species and in research in aquaculture. They restock hundreds of thousands of juveniles every year in the sea and keep monitoring them,” Aquatic Resources Malta CEO Frank Fabri said.

Sea urchins can live for a long time, ‘some say they don’t die’

Speaking to Times of Malta, Mallia said work began in the summer to improve the condition of a group of some 200 adult sea urchins that were harvested from the sea.

“We changed their diet and their environment, and by October they were ready for spawning,” Mallia said.

Unlike the two spawning seasons in the open sea, sea urchins in the laboratory can spawn far more regularly, Love said.

“It’s just a matter of creating the right conditions,” the senior researcher said.

After a sea urchin egg and sperm meet, the fertilised cell divides into two within minutes, and within days they develop an “Eiffel tower-like shape”.

As the days progress, the larva goes from a two-legged creature to four legs, then six and then eight.

After one month, the larva – which would have been floating in the ocean – settles on a rock bed. There, they go through a metamorphosis and take the shape we are familiar with.

Currently, the batch that is in the Marsaxlokk laboratory has gone through the process and is considered to be juvenile sea urchins.

“But at this stage, the juvenile sea urchins are still microscopic,” Mallia said.

It is only after a year that they become the size of a thumbnail, he said.

That is when ARM plans to release the creatures into the wild where the agency also plans to continue monitoring them.

Despite growing at a slow rate, sea urchins can live for a very long time.

“Some say that sea urchins do not die,” Mallia said.

“Even when they have no food they can enter into hibernation and just wait for better conditions.”

However, rising sea temperatures and salinity (the amount of salt in the sea) have meant more disease for sea urchins. Those diseases have meant that many sea urchins have died. With only fishing pressures, sea urchin populations have been able to remain sustainable. But with the effects, of climate change, numbers in Malta’s ecosystem have begun to dwindle, Love said.

ARM CEO Frank Fabri said the sea urchin project is part of the organisation’s long-term strategy.

“All this is an example of how we reflect and implement VisionARM 2050 – based on four pillars: conduct excellence in research; promote the sustainability of aquatic resources through research; invest in the human capital and skills in order to conduct quality research of excellence; and for ARM to become a focal point in the Mediterranean as a research institution.”

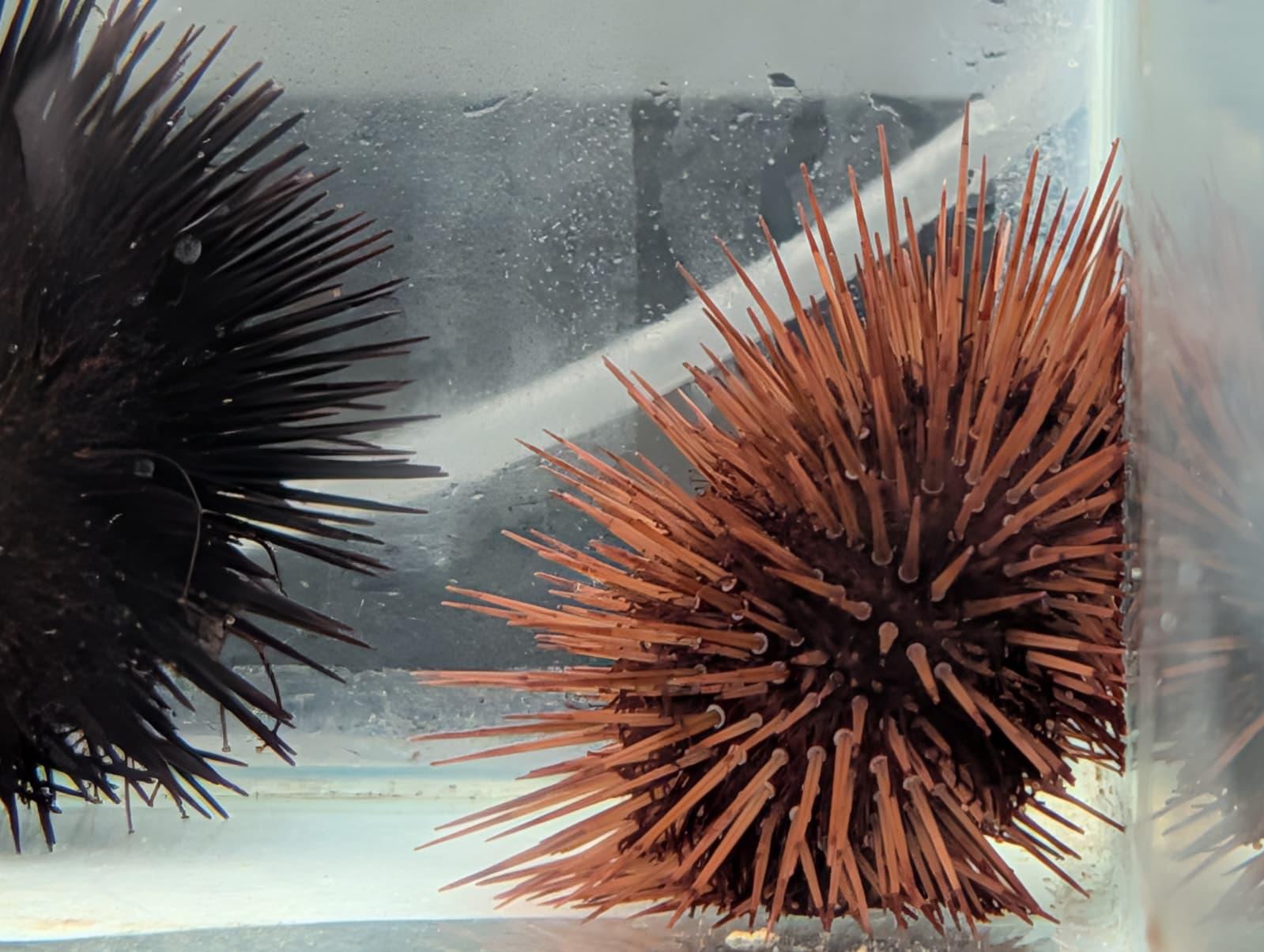

Adult sea urchin

Adult sea urchin