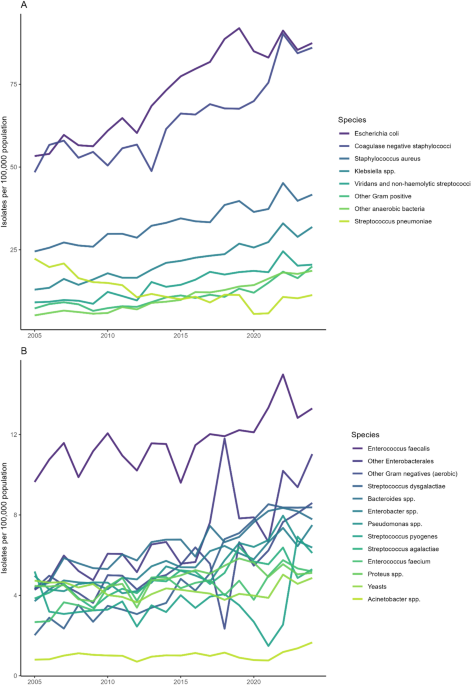

In this ecological study of bacteraemia in Norway from 2005 to 2024, the incidence of bacteraemia increased both in absolute numbers and per 100,000 population. The increase coincided with demographic ageing, rising immunosuppression and cancer incidence, and more than a doubling in the number of blood cultures taken, while the number of hospital admissions per capita declined. E. coli remained the most common pathogen, followed by S. aureus and Klebsiella spp., all of which increased substantially over time. In contrast, S. pneumoniae declined. Regression models showed a steady rise in incidence over the study period, with minimal difference between unadjusted and age-adjusted estimates.

Our findings align with those from other Nordic countries reporting on national or larger regional trends in the aetiology of bacteraemia. Dessau et al. found a marked increase in the incidence of positive blood cultures in Denmark between 2010 and 2022, alongside a 64% increase in blood culture sampling and a relatively stable positivity rate around 10%, arguing that this may be linked to demographic shifts with a higher proportion of elderly4. Two studies from Sweden and Finland similarly reported an increasing incidence of Gram-negative bacteraemias between 2000 and 2014, with E. coli and Klebsiella spp. as the main contributors and a decline in pneumococcal bacteraemia, closely matching our observations5,6. An earlier Norwegian study covering 1999–2008 also documented that bacteraemia were increasing in incidence already then3. Outside the Nordic countries, comparable population-based studies are rare. As examples of the scarcity of nationwide data outside of the Nordic region, a Spanish study from 2010 to 2019 reported a lower overall incidence, but the same increase in Gram-negative bacteraemias and decrease in S. pneumoniae, but was limited to two hospitals in Madrid17, while a single-centre study from Vietnam demonstrated a strikingly high relative incidence of idiosyncratic microbes like the porcine-associated Streptococcus suis and the non-fermenter Stenotrophomonas maltophilia18. Together, these comparisons suggest that a rising overall incidence and a shift towards certain Gram-negative pathogens may represent a broader phenomenon, at least in the Nordic countries though differences in study design, scope, and data completeness complicate direct comparisons.

In our study, the species category distribution among the blood culture isolates also changed over the study period. The most notable decline was observed for pneumococcal bacteraemia. This trend likely reflects the introduction and scale-up of childhood pneumococcal conjugate vaccination programmes in Norway. Similar declines has been reported from other high-income countries following vaccine implementation19,20. In contrast, most other organisms showed marked increases. In other words, the apparent rise in Gram-negative bacteria relative to Gram-positives (not including contaminants) is largely explained by the decline in S. pneumoniae. Within Enterobacteriaceae, the incidence of E. coli bacteraemia roughly doubled, while Klebsiella spp. tripled, underlining the growing importance of these organisms in the epidemiology of bacteraemia. The relative increase in the Klebsiella spp. to E. coli ratio has also been noted in European-level surveillance data, suggesting a wider trend beyond Norway 21. Although a specific association with nosocomial infections is not confirmed by a previous large Norwegian study22, Klebsiella spp. infections are often considered more weighted towards hospital settings than E. coli. A similar distinction applies between Enterobacterales and non-fermenters such as Pseudomonas spp. and Acinetobacter spp., whose proportional changes can serve as ecological indicators of hospital-associated infection patterns23. While the absolute incidence was low, the relative increase in Acinetobacter spp. was also notable towards the end of the study period, in contrast to Pseudomonas spp., whose relative importance decreased. While a major increase in extensively drug-resistant Acinetobacter spp. has been reported from other European countries24, the increase we observe in Norway does not reflect resistant strains. All carbapenemase-producing Acinetobacter spp. are notifiable to the national surveillance system, and no marked rise has been recorded among blood culture isolates. Notably, S. dysgalactiae and anaerobes showed some of the steepest relative increases. The S. dysgalactiae category, comprising β-haemolytic group C and G streptococci, has been identified using consistent criteria despite methodological changes, with MALDI-TOF introduced and routinely implemented by around the middle of the study period. S. dysgalactiae has been recognised as an emerging cause of invasive infection in recent years, and improved diagnostics for anaerobes may also have contributed to their observed increase25. Increases were also seen in viridans and non-haemolytic streptococci, as well as in the “other” categories for both Gram-positive and Gram-negative organisms, potentially indicating an increased ecological diversity in the aetiology of bacteraemia. These patterns may suggest a growing contribution of healthcare-associated or hospital-onset infections as these are sometimes low-virulence or rare microbes that may cause disease in the frail or immunosuppressed, consistent with changes in patient case-mix and invasive procedures26,27. However, our ecological design does not allow for causal, patient-level attribution. National guidelines and laboratory routines for blood culture sampling remained stable throughout the study period, making it unlikely that such changes influenced the observed trends. Furthermore, although Norway has a programme for the medical evacuation of war casualties in Ukraine28, this cannot account for the observed increase, as the programme only began after 2022 and the number of patients transferred has been limited to the double digits.

These microbial shifts occurred during a period when antibiotic consumption in hospitals remained relatively stable in overall volume, with a gradual move towards narrower-spectrum agents and more targeted prescribing10. While total number of defined daily doses (DDDs) per population changed little before the COVID-19 pandemic, antibiotic use adjusted for hospital activity (e.g. bed-days) showed considerable variation between hospitals and years. Broad-spectrum antibiotics such as cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones and carbapenems made up a decreasing share of use, concurring with an increased use of aminoglycosides and glycopeptides, suggesting strengthened stewardship. In primary care—where more than four-fifths of all antibiotics are prescribed—overall use declined between 2012 and 2019, mainly due to reduced prescribing for respiratory tract infections. Although there was a rebound after the COVID-19 pandemic, levels in 2023 were still comparable to those seen in 2019 and well below earlier years. The prescribing pattern has remained dominated by narrow-spectrum agents, particularly phenoxymethylpenicillin, pivmecillinam, dicloxacillin, amoxicillin, doxycycline, and nitrofurantoin, with broad-spectrum antibiotics making up a relatively small and decreasing share of total prescriptions10. Taken together, these developments suggest that changes in antimicrobial use are unlikely to have been the main driver of the observed increase in bacteraemias or the shift towards a higher contribution of Gram-negative organisms, although a contributory role cannot be excluded. The observed increases in incidence among some species may have important implications for infection prevention and control in several different ways29. Increasing incidence of species inherently resistant to certain antibiotics may challenge established empirical treatment regimens. Also, these species may harbour antimicrobial resistance genes on mobile genetic elements, facilitating horizontal transmission between bacterial species, which may further exacerbate the threat of acquired antimicrobial resistance in the longer term. Finally, some of these species have been found in hospital water systems, which—regardless of whether they serve primarily as reservoirs or recipients—highlight the need for attention to environmental hygiene and standard precautions in healthcare settings.

A general demographic trend in high-income countries is declining fertility rates and an ageing population, which together are reshaping both population structure and healthcare expenditure30. The proportion of Norwegians aged 70 years or older increased by 38% during the study period, reflecting this broader pattern. In parallel, due to resource constraints, the healthcare system is under pressure to become more efficient, driven by a shrinking working-age population relative to the number of individuals requiring care. This shift is evident in our data, where the number of hospital bed-days declined by nearly a quarter despite a largely stable number of hospital stays. This suggests a trend towards shorter lengths of stay and higher patient turnover. In parallel, advanced outpatient services, including so-called “hospitals at home”, are expanding. Much of the apparent reduction in hospital activity per patient likely reflects a redistribution of care, with patients more often discharged early to municipal services that now provide an increasing volume of hospital-like healthcare. Together with an ageing population, this may result in a relatively sicker inpatient population with more complex diagnostic panoramas31. In our data, this was reflected in a steeper rise in bacteraemia incidence when expressed per bed-day than when expressed per population. Additionally, markers of immunosuppression, such as the number of individuals collecting prednisolone prescriptions and the number of incident cancer cases, increased substantially over time, both of which are recognised risk factors for bloodstream infections. Prednisolone use represents only one part of a broad spectrum of causes of immunosuppression and likely underestimates the overall burden. However, gastrointestinal cancers, particularly associated with infections due to Gram-negative bacteria, did not increase more than all cancers combined. Furthermore, age has been demonstrated to be associated with shifts in the epidemiology of bloodstream infections, with the relative importance of different pathogens varying across age groups32. Demographic ageing and increasing morbidity, including higher levels of immunosuppression, are likely contributing to the rise in bacteraemias, but our simple adjustment for the proportion aged 70 years or older does not capture these underlying changes. More detailed individual-level data would be needed to clarify their relative impact.

Diagnostic intensity increased substantially during the study period, as reflected by our estimated doubling of national blood culture sampling. Although these estimates rely on extrapolations from data in the Central Norway Regional Health Authority and the University Hospital of North Norway, Tromsø, a similar temporal pattern observed at Oslo University Hospital—which was not included in the national estimate due to its complex catchment area and national functions—supports the plausibility of a nationwide increase in sampling. While absolute numbers are uncertain, the direction of change appears robust across data sources. Importantly, although our approach does not provide a valid estimate of the absolute blood culture positivity rate, the relative stability of the estimated indicator over time, in line with findings from other Nordic countries33, argues against a major shift towards lower-yield or more indiscriminate testing practices. This impression is reinforced by the stable proportion of coagulase-negative staphylococci among all isolates, which accounted for 20% of all isolates in 2005 and 21% in 2024. High quality data on contamination rates cannot be obtained without a prospective design with harmonised criteria across hospitals and laboratories. In their absence, the two indicators we use suggest that the rise in positive blood cultures primarily reflects a real increase in the underlying burden of bloodstream infections, rather than increased contamination or a systematic lowering of the threshold for sampling.

A major strength of this study is the use of a complete national dataset covering all microbiology laboratories performing blood cultures in Norway over a 20-year period. This allowed for an unselected, population-wide analysis with long-term trend data. However, several limitations must be acknowledged. The ecological design precludes causal inference, and we cannot definitively establish whether the observed increase in positive blood cultures represents a true increase in the incidence of bloodstream infections or is driven by increased diagnostic activity, changing indications for blood culture sampling, or improved detection and identification methods. We lack individual-level data on patient characteristics, blood culture indications, sampling rates, and timing relative to hospital admission, precluding analyses that could distinguish between community- and hospital-onset infections or calculate incidence per patient-days at risk. The denominator for total blood cultures taken was estimated based on data from selected regions, and the Oslo hospitals were excluded from this calculation due to their complex catchment areas and extensive national referral functions, which result in an atypical patient mix (Rikshospitalet, literally ‘the national hospital’). Although both Rikshospitalet and Ullevål also provide local and regional services, their activity profiles differ substantially due to variations in patient composition and specialist functions. These differences, rather than regional variation in diagnostic practice, might explain the divergence observed between the Oslo hospitals and other sites. However, the denominator was used mainly to capture the trend in diagnostic activity over time rather than to estimate the absolute number of cultures taken. Although trends at these hospitals support our national estimate, relying on data from only Central and Northern Norway introduces uncertainty. If blood culture activity in other regions followed different patterns, our estimates of national sampling volumes—and thus of positivity—could be biased in either direction. Furthermore, we were unable to fully consider possible changes in contamination rates, although the stability of the proportion of coagulase-negative staphylococci suggest no major changes in blood culture quality. Finally, we relied on aggregated species categories, which limits species-specific interpretations. We did not attempt to model or test statistical associations between incidence and the contextual factors we present. The incidence of bacteraemia increased monotonically and nearly linearly over the study period, and such a secular trend will inevitably correlate with any other factor displaying a steady rise, such as population size, population age, GDP, or even unrelated metrics like food consumption. In this setting, ecological correlations are therefore not informative and risk being misleading, and we considered such analyses to add little value to the interpretation. Future work should prioritise person-level studies with linked clinical, microbiological, and administrative data to better understand and estimate the relative impacts of the drivers behind these trends, distinguish between hospital- and community-onset infections, and explore patient-level risk factors. Improved national surveillance with denominator data on blood cultures taken, hospital admissions, and patient-days could also strengthen future analyses.

In conclusion, the incidence of bacteraemia in Norway increased steadily between 2005 and 2024, accompanied by marked shifts in microbial composition towards Gram-negative organisms. This increase occurred alongside demographic ageing, rising immunosuppression, and increased diagnostic activity, but remained evident after adjusting for population age structure. Although changes in testing practices may have contributed, the stability of the positivity rate and the proportion of likely contaminants suggest that the observed increase reflects a genuine rise in bacteraemia. These findings provide a national reference for bacteraemia trends over two decades and highlight the need for continued surveillance and more detailed, individual-level research to better understand the drivers of these changes.