The Abbey of Saint Sixtus has dealt with a lot in its almost 200-year history. But more recently, the catholic monastery in West Flanders — best known for its premium Belgian Westvleteren beers — has been confronting a double challenge: a thriving black market that has forced it to adapt its centuries-old business model, and a second, potentially greater existential hazard, the Trappist order running out of monks.

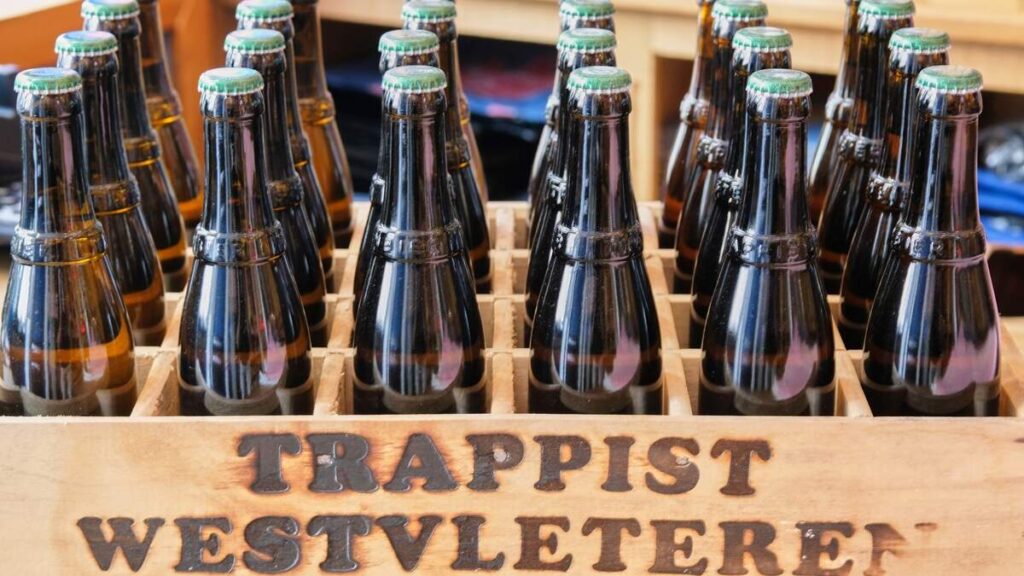

The beer’s popularity can be seen on those mornings when vehicles from across Europe patiently wait to collect pre-ordered crates from forklift drivers in monastic robes, a process cloaked in enough bureaucracy to make it fiendishly difficult to buy. Westvleteren is one of 11 breweries around the world certified by the International Trappist Association. That means their products are made in the vicinity of a Trappist abbey, under the supervision of monks or nuns, and profits are used for charity or the needs of the monastic community. Of the 11, five of those brewers are in Belgium, two in the Netherlands and one each in France, Spain, Italy and England.

Intangible cultural heritage

The monks of Saint Sixtus are on track to brew for just 57 days this year, according to data shared with Bloomberg, leaving the machinery idling for the vast majority of each month. They’re expecting to produce just over 7,500 hectoliters in 2025, earning enough to cover the abbey’s running costs and charity projects. It’s a tiny portion of Belgium’s total beer production, which was around 21 million hectoliters in 2024 according to Eurostat — but the Trappist tradition is part of the reason Unesco has declared the country’s beer culture part of humanity’s intangible cultural heritage.

“Even though the number of monks is declining, their role as guardians of tradition, quality, values and credibility makes them indispensable to Belgian beer culture,” says Krishan Maudgal, Director of the Belgian Brewers Association. “They form the moral and historical foundation on which a large part of the Belgian beer story still rests.”

At first glance, Belgium’s Trappist breweries are thriving. The beer is as coveted as ever and the monks able to reinvest for the future. But their tradition and unusual business model leaves them exposed to unique pressures. The only US Trappist brewery shut down in 2022 and another in Belgium, Achel, stopped selling Trappist beer in 2023 after being stripped of its status and sold to a commercial brewery. Its last remaining monks were moved to another abbey. At stake aren’t just beloved brews — or a way of life that has survived wars and social change — but institutions that provide important economic development and charitable support to their regions.

Westvleteren still has two monks involved in running its brewery, with an extra five stepping in to help with the bottling process. But its much-coveted status has created problems not faced by other Trappist breweries, whose beer is more broadly available in shops and pubs.

Reselling activity

Priced at an average €2.10 per bottle, a thriving gray market for the beer — where it’s bought legally at the monastery and then sold on at marked-up prices elsewhere — has been a persistent challenge for the monks. British website Beautiful Beers demands more than ten times the original retail price per bottle, while Belgianshop.com in the US wants more than $300 for a six pack.

Since 2019, the monastery has been trying to tackle the reselling activity — indirectly opening the door to a more modern approach to business. Out went their so-called “beer phone” that had left customers languishing on hold for hours. It was replaced by an online ordering system, making it easier for the brewery to trace where the beer was going.

To buy the Abbey’s award-winning beer — Westvleteren 12 — a consumer now needs to first create an online account. That’s the easy part. They then need apply a hawk-like attention to the brewery’s online calendar. The random nature of the opening hours of its web store adds some jeopardy. If you find it open, you then must hover in an online “waiting room” for up to an hour before getting 10 minutes in the shop to make your order — the maximum is four of the 24-bottle crates of beer. Customers must provide a car license number and pick a date and time to join the line at Saint Sixtus.

Delivery slots are strictly enforced, and the use of someone else’s car isn’t an option either: You simply won’t be let in. Failure to meet the restrictions will mean you are banned from buying.

In 2023, the brothers took a step away from their strict policy to only sell beer to individual consumers. In an effort to combat what it calls “profiteering” by Dutch resellers, Saint Sixtus decided to export 240,000 bottles per year to a few hand-picked outlets among its Northern neighbors whose margins are much more reasonable. Prices are monitored closely and Dutch stores that don’t stick to the rules are denied further supplies.

“They want to offer an artisanal product — but at a fair price,” says Yves Panneels, who manages communications for two Trappist breweries, including Westvleteren, as well as an abbey of Trappist sisters who make natural beauty products. “They also want fair distribution so that everyone can buy it,” he says in an interview. “Not only the ones who have a lot of money.”

It’s an abbey with a brewery, not vice versa

Philippe Van Assche

General Manager, Westmalle brewery

The Benedictine monks that live in and run these abbeys seek minimal contact with the outside world, but along with a life of prayer and reflection their ethos holds that they must work and provide for themselves — and not rely on charity or donations. It’s a model of self-sufficiency on display at the Westmalle Trappist brewery, just outside Antwerp, which not only produces about 120,000 hectoliters of beer each year but also cheese for sale in specialty stores from its own herd of cows. There’s also a working bakery and blacksmith on site.

Monks have stepped back from hands-on involvement in some abbeys, directing the strategy via a board but leaving the brewing activities to professional employees at larger operations like Westmalle and Chimay, about 80 miles south of Westmalle in Belgium’s French-speaking region of Wallonia.

Philippe Van Assche was working in finance, at what is now BNP Paribas Fortis, when he took over the running of the Westmalle brewery as general manager almost three decades ago. He was, he says, attracted by its approach and business philosophy.

“They wanted to know all the people that work here,” he says in an interview in the brewery’s offices, a short corridor away from the vast tanks in which their beer is fermenting. “It’s an abbey with a brewery, not vice versa.”

Stable profit and production

The idea is to hold profit and production stable, to provide for the abbey, give to charity, and reinvest where necessary in the business. Westmalle’s bottling plant hums and crashes with life during the day as bottles are washed, labeled, filled and prepared for delivery. At maximum capacity, 45,000 are processed per minute. But the production line lies idle outside its one day shift, and doesn’t operate on weekends, as the monks want the staff to work sociable hours. It’s set to be replaced by 2030 with a new modernized facility through a major, self-funded investment in the brewery.

The values of these businesses are a draw not only for consumers but also employees. Fabrice Bordon has held a variety of roles at the Chimay Trappist brewery over the past 24 years. It was a change of pace to join the business after five years at another household name in Belgium: the world’s largest brewer, AB InBev.

“No shareholders, the benefits go to help solidarity, to help the region, to raise the level of life of the inhabitants,” Bordon explains over the phone. Chimay produces around 170,000 hectoliters and employs 125 workers just in the brewery, with another 125 in other functions under the 14 monks in the abbey.

Dwindling number of monks

Still, there’s a longer-term challenge affecting all these monastic institutions: fewer people taking up a vocation as a Benedictine monk. The fear is that dwindling numbers and a failure to recruit could lead more Trappist abbeys — and by extension their breweries and social business models — to follow in the footsteps of Achel, which lost its Trappist designation and was sold to a commercial brewery following the departure of its last monks.

“That’s a challenge that probably was always there — but every year it becomes a little bit more visible and tangible,” says Westmalle’s Van Assche.

However, some see tentative signs for optimism. Bordon has seen the number of monks at Chimay grow from 12 to 14 over the last seven years, plus three novices — though part of this increase is down to monks being relocated from monasteries that have closed down. Still there is a fierce desire from those that are part of these institutions to protect them, not only for consumers, but also for what they contribute to their communities.

“We have been here for 200 years now,” says Westmalle’s Van Assche. “We would like to preserve this beautiful place with a farm, a brewery, a cheesemaker, a place of prayer, a place of rest and silence.”