During the period often described as the “End of History,” in line with Francis Fukuyama’s thesis—or, more precisely, the beginning of a new era of European democracies—the then Republic of Macedonia and the Republic of Bulgaria entered this phase in markedly different ways.

In Bulgaria, the transition was symbolized by the presidency of Zhelyu Zhelev, a former dissident and politically persecuted intellectual who became the country’s first democratically elected president. His leadership marked Bulgaria’s entry into a new liberal era, one that sought to break decisively with the burdens of its communist past.

Across the border, the situation unfolded differently. Macedonia emerged from the Yugoslav federation under the leadership of the Social Democrats’ so-called “young lions,” political figures who had only recently passed through the final congresses of the Communist Party.

For this new generation of leaders, however, it proved difficult to fully abandon the ideological baggage of the 1980s—a decade dominated in the region by Slobodan Milošević. Inspired by Dobrica Ćosić, Milošević revived the most aggressive forms of Serbian nationalism and hegemonic ambition. The consequences of that period continue to resonate across the former Yugoslav space, where the legacy of figures such as Tempo and Boba has repeatedly resurfaced in new political contexts.

While in Sofia, I had the opportunity to meet Stefan Tarfov, foreign policy adviser to Bulgaria’s first democratic president, Zhelyu Zhelev. Tarfov says that Bulgaria’s first democratic government closely followed developments in Macedonia at the time but remained uncertain about how to act “given the circumstances.”

“Macedonia in 1990 and 1991 was still undecided about its future within Yugoslavia,” Tarfov explains. “At the same time, Bulgaria was in a very difficult socio-economic situation. We feared Greece’s reaction and were deeply concerned by Milošević’s increasingly aggressive behavior. In 1992, it was not easy to formulate a clear position.”

According to Tarfov, in an effort to better understand the broader regional dynamics, Bulgaria sought insight from the office of French President François Mitterrand.

“President Zhelev wanted first-hand information on developments in Yugoslavia. From Paris, I was informed that [Robert] Badinter would soon announce a recommendation to recognize Macedonia. That news came as a great relief. I relayed the news to the President’s Office and then to the government in office at the time. When I shared the information, the cabinet could not hide its satisfaction. The decision was made, and Bulgaria became the first country to recognize Macedonia’s independence,” Tarfov recalls.

Zhelev’s Liberal Vision and the Clash with the Zhivkovist Matrix

Zhelyu Zhelev, a liberal intellectual and a victim of the communist regime of Todor Zhivkov, held views on the Macedonian question that ran counter to the dominant narrative. Despite strong resistance from the Bulgarian Socialist Party (BSP)—the political heirs of Zhivkovism—Zhelev sought to institutionalize these positions within Bulgaria.

“We were facing major challenges in Bulgaria’s democratization. Although we had won power, the BSP was in opposition but retained significant influence within the institutions, where many of their people were still present. On the Macedonian question, the BSP attacked us fiercely, and their nationalism was largely embraced by a public that had not yet abandoned the Zhivkovist mindset,” Tarfov explains, describing both Zhelev’s views and the obstacles confronting his policies.

For years, Moscow has skillfully influenced Bulgarian positions and promoted narratives questioning the existence of the Macedonian language and identity. This may help explain why, from Zhelev’s time onward, Bulgaria’s recognition of Macedonia as an independent state did not explicitly include recognition of the Macedonian language. Many Bulgarian politicians and intellectuals continue to insist that the Macedonian language is merely a dialect of Bulgarian and that the “Macedonian nation” is an artificial construct created by communist Yugoslavia. At the same time, it is increasingly evident that Bulgarian society itself lacks a clear consensus on this issue.In any case, such propaganda spills over into Macedonia, where it is often used as an alibi for prolonging stagnation in the country’s European integration process—arguably aligning with the strategic objectives of the Russian state with regard to Macedonia.

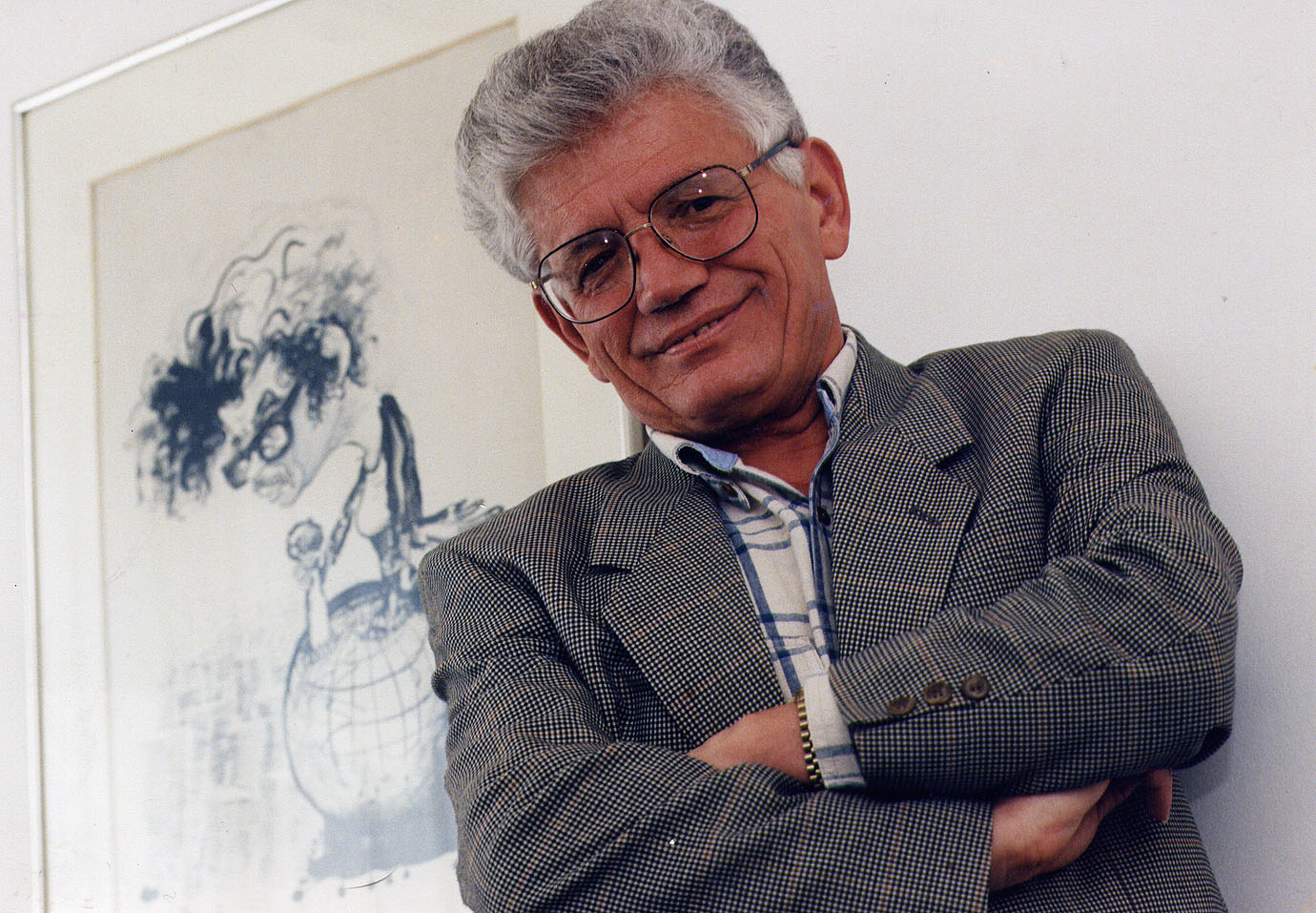

Македонскиот академик и писател Божин Павловски | Фото: Dzide, јавен домејн, Викимедија комонс

Македонскиот академик и писател Божин Павловски | Фото: Dzide, јавен домејн, Викимедија комонс

Macedonian academic and writer Božin Pavlovski | Photo: Dzide, public domain, Wikimedia Commons

Yet Zhelev’s stance on the language issue was radically different from the mainstream. This is confirmed by Macedonian writer Božin Pavlovski in one of his personal notes. According to Pavlovski, during Macedonia’s independence, “the great Bulgarian intellectual Zhelyu Zhelev was the first to extend a hand to the Macedonian people and to our state.”

As Pavlovski recounts, as early as 1988 he hosted Zhelev at his legendary restaurant Misla, where they agreed that Zhelev’s book Fascism would be published in the Macedonian language.

Pavlovski recalls that Zhelev made a remark that deserves to be remembered:

“You often make a mistake when you say that your largest diaspora is in America or Australia. Your largest diaspora is in Bulgaria,” Zhelev said on that occasion.

Zhelev would later clearly demonstrate—on two separate occasions—his own approach, and that of the Bulgarian state at the time, toward Macedonia. During the Greek embargo and the international sanctions against Serbia, Bulgaria provided the only corridor through which Macedonia could secure oil supplies from the Black Sea.

As Tarfov recalls, this was followed by an initiative by then Serbian President Slobodan Milošević, who together with Konstantinos Mitsotakis invited Bulgarian Prime Minister Dimitar Popov to Athens to discuss the possibility of a new partition of Macedonia.

“Zhelev was categorical and forbade Popov from traveling to Athens,” Tarfov says. Finally, as Tarfov also notes, Zhelev rejected a proposal advanced by former Bulgarian communists—backed by Moscow—for the creation of a new Balkan federation that would include Macedonia. The ultimate goal, he says, was to pull Bulgaria away from its European aspirations.

“Zhelev had absolutely no issue with the existence of the Macedonian language. You know that his book was translated into Macedonian precisely to demonstrate that clearly. There were many gestures through which we sought to show readiness for a different quality of relations, despite the obstruction we faced within institutions and from an intellectual elite intoxicated by Zhivkovism,” Tarfov explains.

However, he adds, there was unfortunately no comparable response from the other side of the border.

“For example, the house in Kruševo where the Kruševo Republic was proclaimed belonged to Georgi Tomalevski, who, after the republic’s collapse, moved with his family to Sofia. He was a well-known revolutionary, yet neither his house nor his name are marked—there is only a plaque stating that the Kruševo Republic was proclaimed there,” Tarfov says, recalling the early 1990s.

The Turbulent 1990s

By the mid-1990s, the Social Democrats in Macedonia held near-absolute power. Their failure to implement reforms grounded in liberal-democratic values would later prove to be a serious weakness, ultimately costing them their hold on power.

As a journalist and correspondent for TV A1 in Brussels, where I regularly covered NATO and EU affairs, I had the opportunity to witness what could be described as a “misunderstanding” between Macedonia and the NATO administration.

Borjan Jovanovski as a correspondent and program host reporting from Brussels | Photo: Evrozum

At the time, NATO insisted on regional cooperation among the signatories of the Partnership for Peace, including Macedonia and Bulgaria.

In 1996, then Prime Minister Branko Crvenkovski traveled to Brussels for talks on this cooperation. As he informed us, his assessment was that Macedonia could not easily cooperate with Bulgaria because of numerous unresolved issues from the past.

I reported this accordingly and later attended a briefing with NATO’s spokesperson at the time, Jamie Shea. I asked for clarification—and received it.

“It’s quite simple. We are aware that you carry unresolved issues from the past, and the aim of our policy is to offer a framework of support and cooperation in areas where there are no disputes—provided that both sides genuinely seek NATO membership. By building mutual trust under our mentorship in the fields of security and defense, you will also create an atmosphere in which the more difficult issues can later be addressed more easily,” Jamie Shea explained to me.

His explanation seemed logical, and I had no further questions. I prepared a report and broadcast it in the TV A1 news. I was shocked by the level of political anxiety with which the report was received by the ruling elite at the time. I was accused of being young and inexperienced, of not understanding the situation, and was even subjected to security checks and “informal” conversations with my “colleagues” to determine who was allegedly paying me.

Stefan Tarfov, my respected interlocutor in Sofia with extensive diplomatic and intellectual experience, also shared his frustrations from that period.

He recalls that during a reception at a meeting of the Central European Initiative in Italy, then Polish Foreign Minister Bronisław Geremek wanted to introduce him to Macedonian Prime Minister Branko Crvenkovski.

“I was pleased by the opportunity, but when I met the then very young Crvenkovski, I sensed a certain defiance and a need to assert superiority in his attitude toward me, as the Bulgarian ambassador to Italy at the time,” Tarfov says.

As he adds, Geremek, speaking with his political and intellectual authority, emphasized the need for cooperation between Bulgaria and Macedonia within the framework of European integration. Crvenkovski, however, responded in a surprisingly blunt and undiplomatic manner, saying there was no need for such cooperation because Macedonia was far ahead of Bulgaria and would enter the EU much earlier.

“That conversation ended awkwardly, and I realized that he was no different from our BSP politicians back in Sofia,” Tarfov recalls.

Regrettably, Macedonia failed to make use of Zhelev and his vision for building good-neighborly relations. By the early 2000s, former communists and security service affiliates had once again regained influence within Bulgarian state institutions. Bulgaria joined NATO in March 2004 and became a full member of the European Union in 2007. This year, together with Romania, it joined the Schengen Area, and as of January 1, 2026, Bulgaria will also enter the eurozone—completing its European integration, despite the fall of yet another government and preparations for new parliamentary elections, whose number few can even keep track of anymore.