Some of the Nationwide programmes over the past year have been a reminder of how much religion has shaped life in Ireland – even today – despite the huge societal changes that have taken place.

Stories such as the anniversary of Daniel O’Connell’s birth and the history of the Huguenots still have strong echoes now as they involve issues of human rights, the use of force and demographic change.

There was also a 19th Century example of Irish attitudes provoking the outrage of an American ambassador.

However, the changes have been seismic.

Most of us are used to thinking of the Catholic Church as a dominant force in this country.

That was in the 20th Century, but that was something of a historical aberration. We sometimes forget that the Catholic religion was suppressed for centuries before that.

Indeed just a few generations before the foundation of the State, the Church was nervous about building its own cathedral in the Protestant-dominated Dublin of 1825.

Even though it was built as the Penal Laws were ending, the Catholic Church backed out of a plan to build it where the GPO now stands on O’Connell St and picked a more discrete location off the main thoroughfare on Marlborough Street, as a temporary measure.

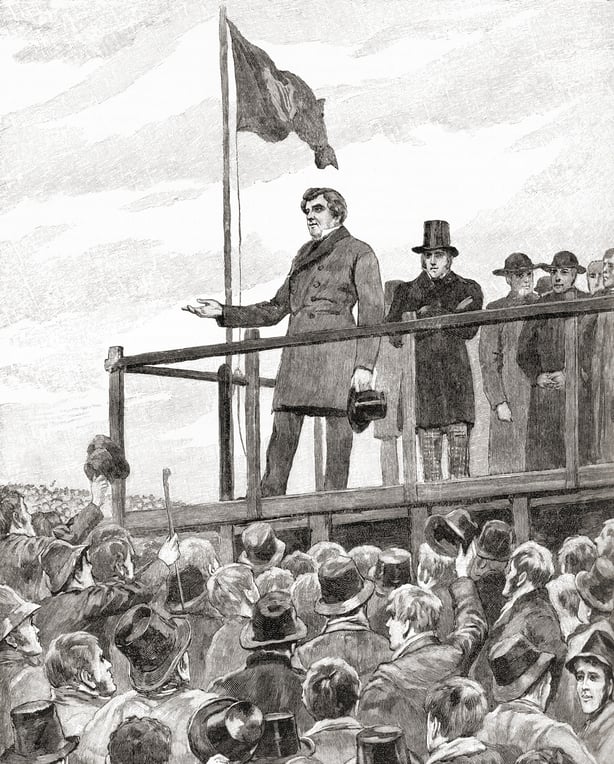

Daniel O’Connell led a campaign for Catholic Emancipation in the 1800s

Fr Kieran McDermott, the cathedral’s administrator, said the church at the time did not want to “push their luck”.

In August, Nationwide marked the 250th anniversary of the birth of Daniel O’Connell, who led a successful campaign to assert the rights of Catholics and who also tried to repeal the Act of Union with Great Britain.

O’Connell insisted on a non-violent campaign using legal challenges and mass protests known as ‘monster meetings’ to effect change.

Interestingly, historian Dr Patrick M Geoghegan, of Trinity Long Room Hub, said the revolutionaries of 1916 had despised O’Connell’s non-violent approach.

This was largely because O’Connell had backed down under the threat of British military force by cancelling a repeal monster meeting.

But Dr Geoghegan said that in later years, Eamon de Valera had come to believe O’Connell was actually right in that and had laid the groundwork for independence.

Daniel O’Connell started a movement to repeal the Act of Union with a series of so-called ‘monster meetings’ around the country

The initiative was founded 50 years ago to give children in the North holidays in the US and away from the Troubles.

We gave a brief history of the Troubles up until then, which had its origins in a civil rights campaign by Catholics in Northern Ireland.

They had been denied equal rights in housing, employment, and the right to vote.

Watching archive footage of the civil rights marches in the late 1960s, it was hard not to have a sense of déjà vu and see it as a continuation of O’Connell’s protest movement over 100 years previously and also be reminded that history often repeats itself.

In the 1960s, the growth of liberalism and the civil rights movement was emerging in different forms throughout the western world.

There were demands for equal rights for African Americans, for women and there were anti-war protests.

The ideology of western liberalism, with its emphasis on individual rights and equality, is believed to have evolved from Christianity.

This type of liberalism is most obvious in the philosophy of the Quakers – a Christian sect who from the start gave equal status to women and advocated many progressive policies such as non-violence and prisoners’ rights.

They also campaigned against slavery in the nineteenth century.

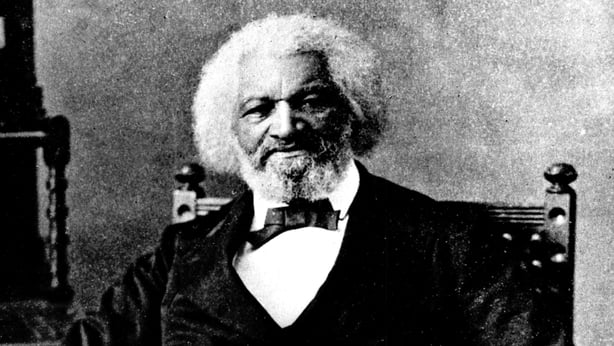

The Quakers hosted the American anti-abolitionist and former slave Frederick Douglass when he came to Ireland in 1845.

They provided their meeting house in Temple Bar for one of his meetings.

US abolitionist Frederick Douglass met Daniel O’Connell while visiting Dublin in 1845

Douglass admired O’Connell, who campaigned robustly in the House of Commons for the abolition of slavery.

O’Connell had enraged the US Ambassador to Britain six years earlier by refusing to shake his hand and calling him a “slave breeder”. This caused enormous controversy at the time.

While we were filming the O’Connell piece for Nationwide during the summer, controversy erupted when the US Ambassador to Israel angrily criticised Ireland’s attitude to his host country.

The issues were very different, but again Ireland found itself on the progressive side of world opinion.

That stance seems to echo the experience of the majority Catholic population here and that denial of their rights for centuries through the Penal Laws.

However, in February, Nationwide broadcast a piece about the Huguenots in Dublin who would have held a different view on the issue when they started arriving here in the 17th Century.

They were French Protestants who were persecuted in their own country by Catholics and whose experience gave the term ‘refugee’ to the world.

The Huguenot cemetery in central Dublin

A high proportion of them were nobles and they were invited to Ireland explicitly to help the Protestant population.

Huguenot families like La Touche and D’Olier had no doubt whose side they were on in the religious wars of late 17th Century Ireland and it is recorded that 3,000 Huguenots fought for William of Orange at the Battle of the Boyne.

They were rewarded for their efforts and became prominent bankers and property developers in Dublin.

Descendants of the La Touche and D’Oliers helped found the Bank of Ireland.

At that time, the Protestant population seemed secure in its power in Dublin.

Many pieces of research had to be left out because of the time constraints in a half hour programme – for instance that in 1715, Dublin city was nearly 70% Protestant.

However, the Catholic population grew with migration from the countryside and by 1800 the percentage of Protestants had dropped to 30% of the city – defined as an area between the canals plus the villages of Donnybrook, Irishtown and Ringsend.

A survey in 1766 noted that there was a sectarian division in the city with the east, both north and south of the Liffey, being solidly Protestant, while the west was predominantly Catholic.

Coincidentally, when Daniel O’Connell fought a duel in 1815, his opponent was a man of Huguenot descent called John D’Esterre.

A member of Dublin Corporation, D’Esterre had challenged O’Connell to a duel for describing the council as “beggarly”.

When O’Connell emerged victorious and D’Esterre was fatally wounded, Catholics responded with jubilation.

The suspicion had been that the duel was orchestrated to destroy O’Connell – by death if he accepted the challenge, or by disgrace if he refused.

But O’Connell regretted the killing for the rest of his life and when the American Ambassador in London challenged him to a duel for his “slave breeder” remark, he refused.

The story of St Mary’s, formerly known as the Pro Cathedral, was broadcast on Nationwide in November

It was once a British military prison and part of a military complex with the Royal Barracks across the road, later called Collins Barracks, and a military church beside it, along with a school for garrison children.

It must have been a very different Dublin with the1,500 British soldiers based in that barracks and about 3,500 more throughout the city.

Also the Protestant population of Dublin city, which then included suburbs like Rathmines and Kingstown (now Dún Laoghaire), was still 20% in 1911.

But 1916 and the War of Independence – which broke out after decades of constitutional nationalism failed to produce Home Rule – led to a big drop in the number of the Protestants.

The numbers continued to decline to 3% in Dublin by 1991. The Catholic Church had been gaining stature in the late 19th Century and became a dominant force the 20th century, which was perhaps inevitable when it had the opportunity to wield power after centuries of being suppressed.

But just as Protestantism declined in the 19th Century, Catholicism started to decline in the late 20th Century.

The number and percentage of Catholics has started to drop – both because of demographic change and from people declaring they do not have a religion.

Dublin is now undergoing another demographic change with the growth of different religions, principally Islam, Hinduism and Orthodox Christians.

The combined percentage of those who described themselves as Catholic or Protestant is now just over 72% in Dublin.

For the moment the city is still dealing with the effects of the Protestant Reformation.

St Mary’s Cathedral on Marlborough Street was finally declared the official Catholic cathedral of Dublin this year – the first in 500 years.

The research on the Protestant population of Dublin comes from an article ‘The Population of Dublin in the Eighteenth Century with Particular Reference to the Proportions of Protestants and Catholic’ by Patrick Fagan in Eighteenth-Century Ireland Society Vol. 6 (1991).