A major new publication is reshaping what is known about the origins and development of photography in Malta. 100 Years of Photography in Malta by Charles Paul Azzopardi, published by Midsea Books, challenges long accepted colonial narratives and presents the most comprehensive reconstruction to date of photographic practice on the islands during the 19th century.

For decades, Maltese photographic history was believed to begin in 1840, when French painter Horace Vernet demonstrated photography in Malta while travelling through the Mediterranean. This account was reinforced by the presence of British calotypists connected to William Henry Fox Talbot in the 1840s and by the establishment of a commercial studio by Leandro Preziosi in 1858. According to this view, photography arrived late and largely through foreign initiative.

The new study overturns this assumption. Drawing on extensive archival, legal and commercial research, it demonstrates that photography was practised and publicly exhibited in Malta as early as 1839, the same year the medium was announced in France.

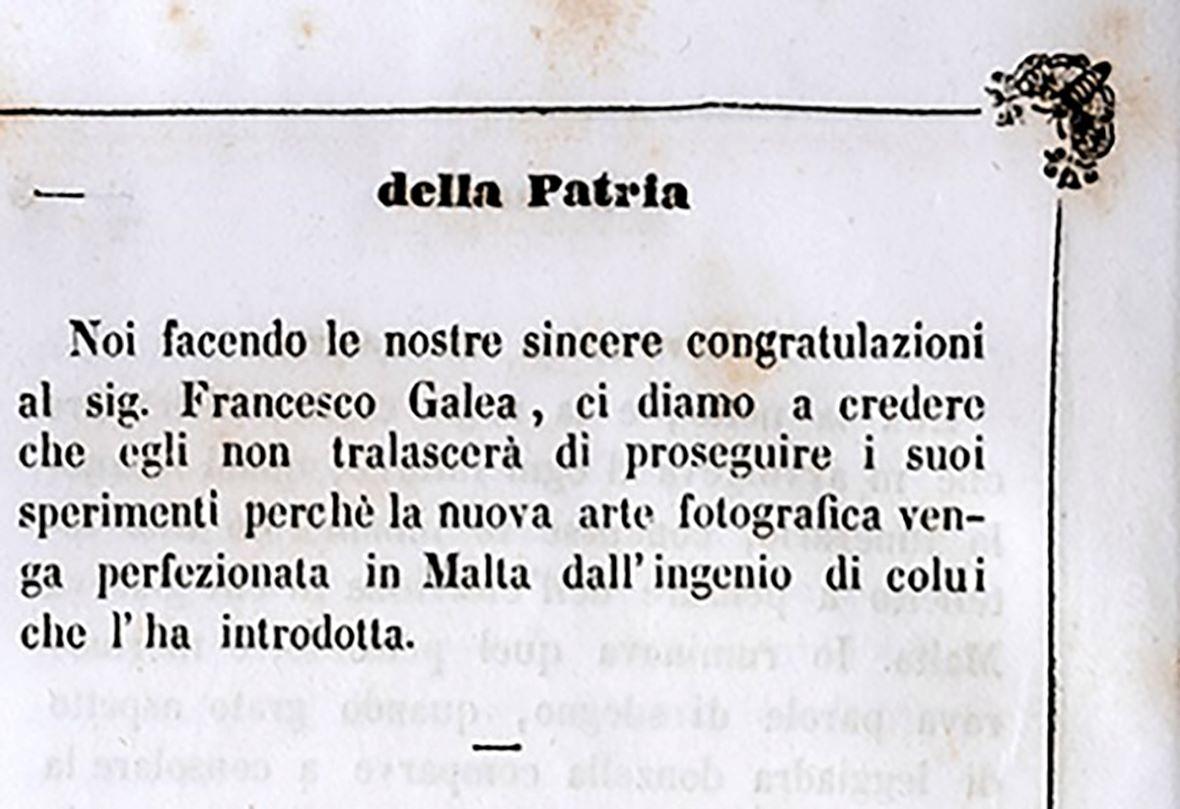

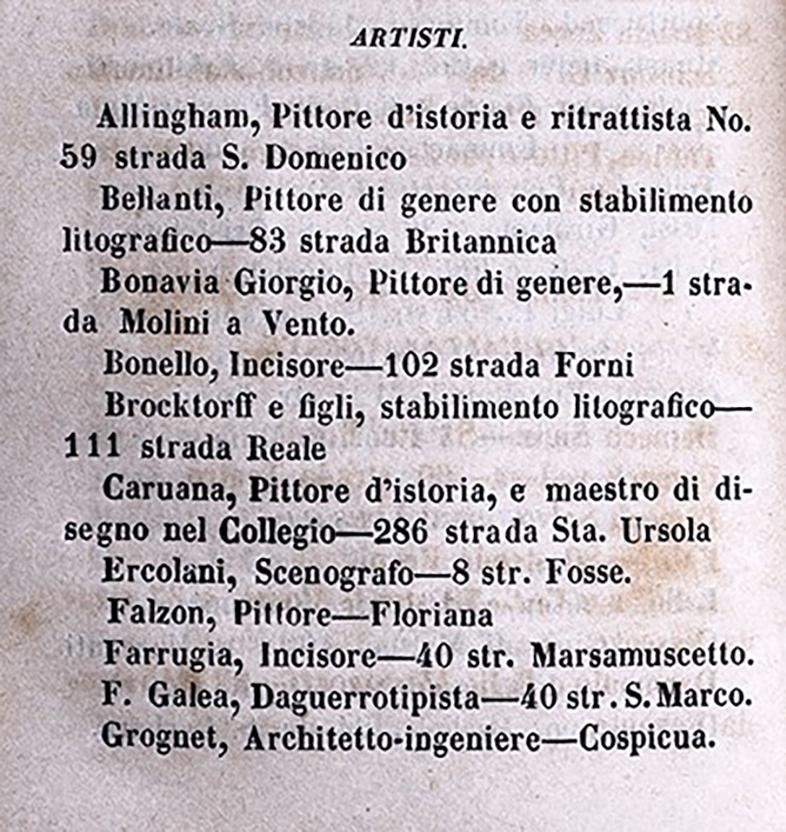

Crucially, the earliest documented practitioner was Maltese. Francesco Galea, a glass and mirror maker and early lithographer, operated a photographic studio in Valletta, placing Malta among the earliest adopters of the new technology.

The research identifies a diverse and active photographic community that developed well before the mid-19th century. Among early operators were Italians Corani and Labruyere, Maltese partners Ardoino and Schranz, English photographer James Robertson, and Dr Giuseppe Micallef, a lawyer who later became a magistrate. Preziosi, long regarded as Malta’s first professional photographer, emerges instead as one of several early entrants, not the pioneer.

The study also reframes the role of women in Maltese photographic history. Although studio ownership and professional recognition were overwhelmingly male, women played a decisive role in sustaining and expanding photographic enterprises.

Preziosi’s studio relied on premises owned by his wife Lucrezia Metropoli, whose contribution has gone largely unacknowledged. Sarah Ann Harrison opened Malta’s first female-run studio in Senglea in 1864, while Adelaide Anceschi, later known as Mrs Conroy, moved from apprenticeship to professional independence in the late 19th century.

Despite this, the first Maltese woman formally recorded as a photographic operator appears only in 1900, when Giuseppina Grech Cumbo inherited and legally operated her father’s studio.

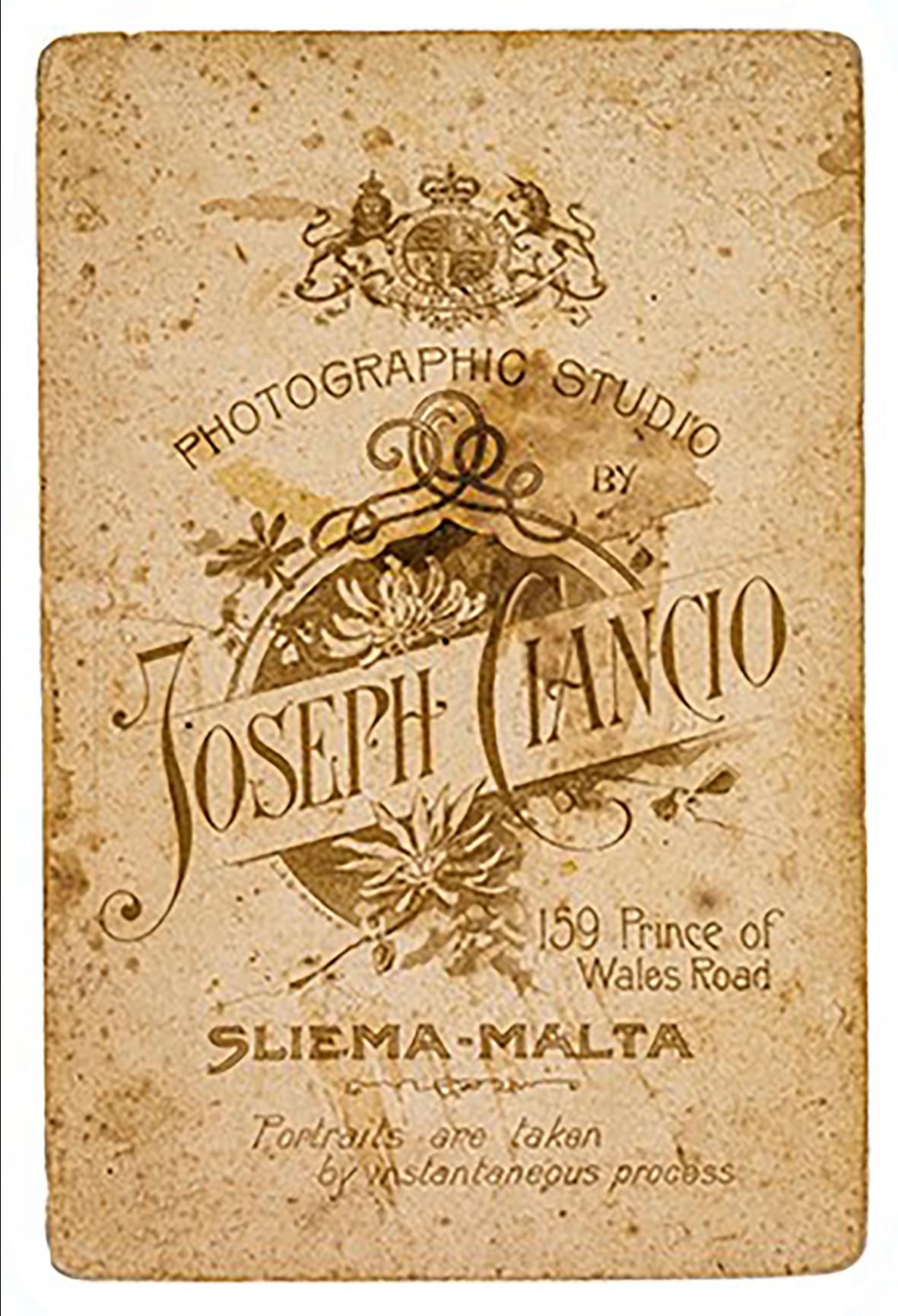

Beyond individual biographies, the book explores photography as a business embedded in Maltese society. It examines supply chains, partnerships, rivalries, legal disputes and insolvencies, revealing how photographers navigated colonial administration, tourism and local demand. Long-standing questions are reopened, including the true origins of the Ciancio photographic dynasty and the deeper commercial networks behind figures such as Blackman of Ħamrun.

A work of extraordinary ambition and integrity, a monumental act of scholarship and a deeply personal journey

The scale of the research is unprecedented. More than 400 photographic operators are identified, verified and placed within a precise chronological and geographical framework. The work integrates business records, court documents, trade notices, visual material and comparative international research, producing a reference work that fundamentally alters the field.

Simon Hill, President of the Royal Photographic Society, who wrote the book’s foreword, describes it as “a work of extraordinary ambition and integrity, a monumental act of scholarship and a deeply personal journey”. He notes that reconstructing “the intertwined narratives of artistic expression, technological innovation and socio-economic change across a century” is formidable in any context, but especially so for “a small island nation whose documentary resources were scattered and, in many cases, almost lost”.

Hill emphasises that the book goes beyond aesthetics, placing photography within Malta’s social and economic history. “The inclusion of legal and financial records, carefully contextualised, allows us to see photography not in isolation but as part of the broader development of Maltese society in the modern age,” he writes, calling it “one of the most sophisticated integrations of visual history and economic history” he has encountered.

The human dimension is central to the narrative. Hill highlights the recovery of forgotten practitioners and anonymous sitters, observing that “Charles gives these individuals dignity and presence” and restores them “to their place in the lineage of Maltese creativity”.

The publication also serves as an argument for preservation. It underscores the absence of a national institution dedicated to Malta’s photographic heritage and highlights the establishment of the Malta Image Preservation Archive as a response to this gap.

Hill describes the work as “a call to preservation and recognition” and argues that Maltese photography deserves the same institutional support afforded to archaeology, fine art and architecture.

100 Years of Photography in Malta positions itself as a definitive reference for future scholarship.

By revising timelines, challenging entrenched narratives and restoring Maltese practitioners to the centre of their own history, it marks a decisive shift in how photography in Malta is understood, studied and valued.

100 Years of Photography in Malta by Charles Paul Azzopardi, published by Midsea Books, is available at all leading bookshops. Visit midseabooks.com for more information.