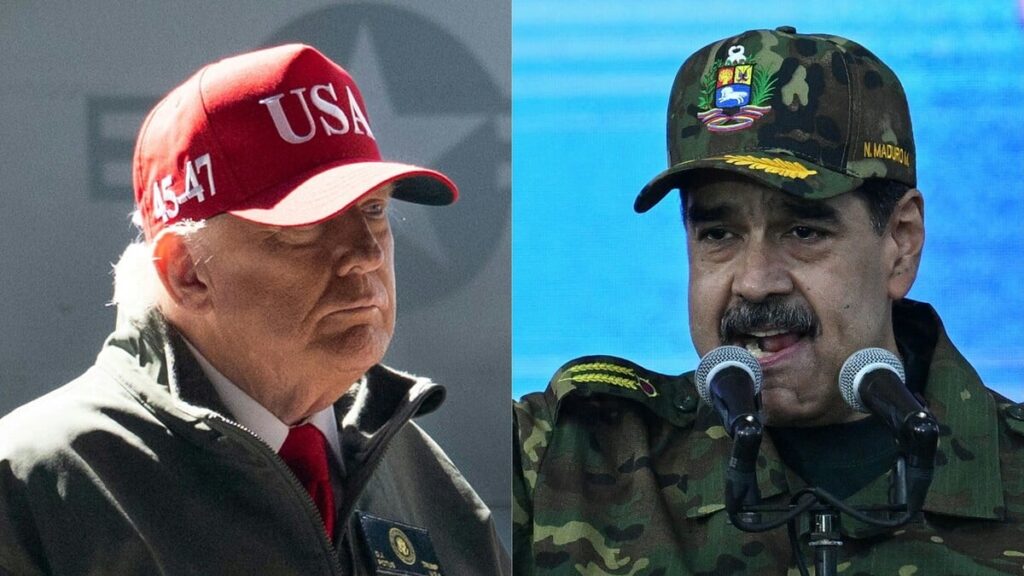

The United States struck Venezuelan capital Caracas early on Saturday with airstrikes, with President Donald Trump announcing he had captured President Nicolas Maduro and flown him out of the country and later saying the US would run the country in the interim.

Also read:Venezuelans in Luxembourg describe ‘happiness’ and ‘uncertainty’ after Maduro capture

Political scientist scientist Anna-Lena Högenauer at the University of Luxembourg talks about what could happen in Venezuela now.

Can we now expect a peaceful transition in Venezuela or is there a risk that the country will fall into chaos?

At the moment, I don’t really see either one or the other. What we are seeing is that things are very calm. That could be because people are in a state of shock because they were not prepared for the attack. But the opposition is also keeping a very low profile. This means that they do not currently believe that any protests [from them] would be successful.

You also have to remember that the country still has a vice president and a complete government. This means that the regime itself has not yet been toppled. The US is optimistically assuming that it will all collapse now, but with a military-backed government this is questionable. The opposition seems to assume that change will not come so quickly.

The last elections in Venezuela took place in the summer of 2024, when Maduro declared himself the winner, but the election is considered to have been rigged. Opposition candidate Edmundo González was recognised as the legitimate president by many organisations, including the EU. But is it likely that he will take power in the near future?

No, I don’t think so. As I said, there is a vice president. I assume that she will initially stand in as a deputy. If this government does not collapse, then there will be no new elections. For there to be a regime change, you would actually need major protests to force new elections, and it very much depends on the role of the military. It’s still very early days, of course, but at the moment I don’t see any signs of a regime change.

How should we assess the significance of the US military action on Saturday?

In a way, it is a destabilisation of the region. You can see that the countries of Latin America are divided. There are countries that support the [military] action, for example Honduras, Chile, Ecuador and Argentina, and countries that are very critical, emphasising that it is an attack on a sovereign state. These countries include Brazil, Colombia, Cuba and also Mexico.

The question now is to what extent the US is prepared to interfere militarily in the affairs of other countries in order to procure raw materials and to what extent governments that disagree with this can be removed militarily. This [US military] action is also a nod in the direction of Cuba and Nicaragua, where there are also left-wing governments that the US might like to have removed.

Is this perhaps also a nod in the direction of Canada and Greenland?

I think not so much towards Canada, because Canada is a bit bigger, but Greenland might be. Officially, of course, the Venezuelan case is about drugs. The official legitimisation is that Maduro is actually a drug lord and not a president and that it is a strike against drug gangs. But we have seen that oil tankers have been detained.

It’s [also] about the Americans playing a role in the production of oil again and getting the oil cheaply – this is also relevant to the security of other countries. Greenland has important natural resources, Ukraine has important natural resources, and there too we saw that the Americans wanted to help extract these natural resources, at least in early peace agreements.

Does this mean that “America First’ is now a new maxim in the international world order?

Yes, potentially. However, this move is also controversial in the US itself. A large part of the population was already against the smaller attacks on the drug boats. An attack on the state itself is actually overwhelmingly rejected. There are certainly critical voices, even among Republicans, who point out that Congress has not authorised any military action at all. It is constitutionally questionable.

How should this action be categorised under international law?

It is very problematic under international law. After all, it is a military attack on a sovereign state that posed no direct threat to the US. Even if there were drug boats, that is not a reason for a military attack. There was no declaration of war beforehand, so in that sense it was an attack, and the head of state was kidnapped, even if he is now being called a drug lord. But of course he is a head of state, even if his democratic legitimacy is questionable.

About the person

Anna-Lena Högenauer © Photo credit: Universität Luxemburg

Anna-Lena Högenauer is a professor of political science at the University of Luxembourg. She studied at King’s College in London and the College of Europe in Bruges. She also holds a PhD in political science from the University of Edinburgh. After her studies, she worked at Maastricht University before moving to Luxembourg in 2014.

(This article was originally published in the Luxemburger Wort, translated using AI and edited by Kate Oglesby.)