Trump administration officials on Wednesday began outlining a makeshift strategy for taking indefinite control of Venezuela’s oil sales, as they race to maintain stability within the nation after overthrowing its leader.

The ambitious, multi-part plan centers on seizing and selling millions of barrels of Venezuelan oil on the open market, while simultaneously convincing US firms to make expansive, long-term investments aimed at rebuilding the nation’s energy infrastructure.

The US would maintain control over the initial revenue generated from the oil sales, officials told lawmakers and energy executives, with plans to ensure that those funds “benefit the Venezuelan people.”

Yet just days after President Donald Trump authorized the capture of former Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro and declared the US “in charge,” those scrambling to map out a long-term plan for the country are still facing far more questions than they have answers.

“The United States will have a lot of challenges thinking that they’re just going to bring US companies down into Venezuela and they’re going to operate and turn this around,” said one oil and gas industry source in touch with top Trump officials. “That’s not reality.”

The vision laid out by senior Trump officials, led by Energy Secretary Chris Wright and Secretary of State Marco Rubio, would represent an unprecedented exertion of control over a foreign country’s oil resources with no clear timetable or guarantee of success.

It raises immediate logistical challenges as well as a range of thorny legal and national security dilemmas, according to interviews with a range of industry sources and lawmakers as well as current and administration officials, threatening to entangle the US in a messy foreign policy project that could turn politically disastrous.

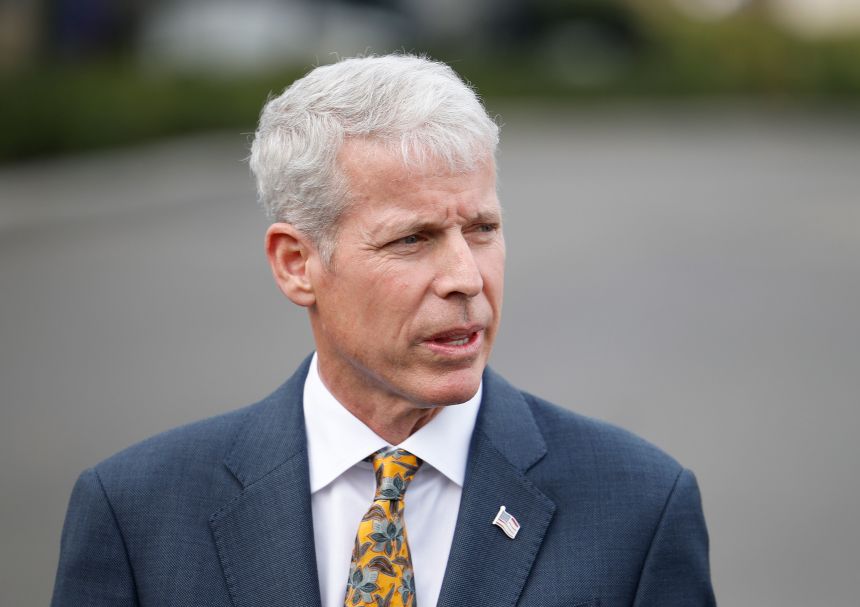

Wright and Rubio nevertheless expressed confidence Wednesday in their approach, with Rubio telling reporters after a classified briefing on Capitol Hill that the administration was “not just winging it.”

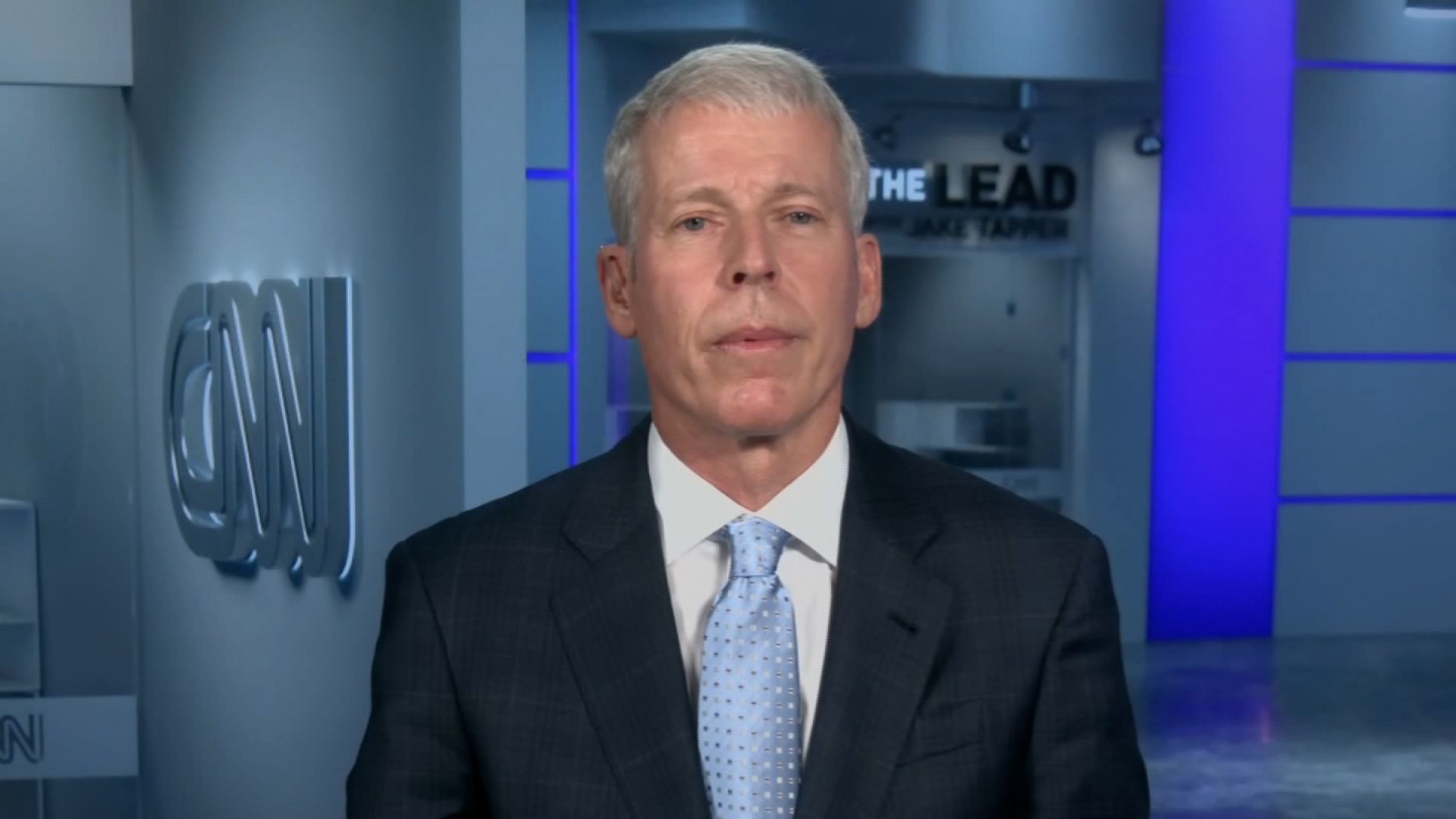

Wright, who spent the day in Miami meeting with industry executives at a Goldman Sachs conference, told CNN that he was getting “barraged” by companies telling him, “We’re interested. How can we get involved?”

But pressed on the specifics of the strategy, they offered only a vague sketch of a monthslong campaign that appeared still very much a work in progress.

Rubio, in private briefings and conversations with lawmakers, has stressed the importance of the next several weeks in managing Venezuela’s transition, including cutting off US adversaries like Russia and China from the nation’s oil supply and quickly generating revenue that can be used to keep its critical services running.

The administration is planning to oversee the sale of an initial 30 million to 50 million barrels of Venezuelan oil that was already under sanction, generating an initial windfall that Rubio told lawmakers would be funneled back into the country. Over time, the US would sell more oil as it’s produced, with the proceeds supporting investments in Venezuela that officials view as crucial to maintaining the interim government’s stability.

But the administration has so far declined to lay out a timeline for how long it will keep control of Venezuela’s premier export, nor has it officially secured the cooperation of interim President Delcy Rodriguez or Venezuela’s state-owned oil company, Petróleos de Venezuela.

“The immediate thing that we’ve got to do is to make sure that this current operational government that’s there today has got to have some resources to pay their bills,” said GOP Sen. Mike Rounds, who sits on the Senate Armed Services Committee. “The intent is to make sure that it doesn’t go into chaos.”

Petróleos de Venezuela said Wednesday that it was in negotiations to sell oil to the US, while Wright told oil executives in Miami that the administration was in “active dialogue” with Venezuela’s leadership.

Also unclear is the legal authority for such an arrangement, which administration officials have openly acknowledged is being negotiated with Rodriguez under the threat of paying “a very big price, probably bigger than Maduro” if she doesn’t agree, as Trump put it.

Trump officials on Wednesday were also still working out how to manage the revenue generated from its sales of Venezuelan oil, telling lawmakers that the US would not rely on the Treasury Department but utilize a collection of international oil traders and offshore bank accounts to sell the oil and manage the resulting cash.

The unorthodox scheme alarmed some lawmakers, raising questions over how the government would manage oversight of the money, as well as decide who gets the funds and track their distribution.

“I have never in my entire life in public service and as a former [Office of Management and Budget] employee, ever heard of anything like this,” said Democratic Rep. Melanie Stansbury of New Mexico.

One former US diplomat with extensive experience in the region told CNN that it didn’t make sense for the Treasury Department to handle the kinds of transactions the administration appears to have in mind.

“The US Treasury is not set up to handle commercial transactions like this,” the former diplomat said. “The Treasury takes in receipts from people who pay taxes, tariffs and fees. They take in money in a way that is consistent with its legally authorized mission and then it disperses those in a way which is governed by law.”

Wright told CNN on Wednesday evening that the administration was “still working out the logistics” of how it plans to sell the oil and deposit the proceeds.

“There’s some legal things that are involved in that,” Wright said. “But whichever account this ends [up] in — I’ll know in 24 hours — is going to be controlled by the United States government.”

Energy Secy.: Oil companies ‘won’t need convincing’ to invest in Venezuela

Ahead of a Friday meeting at the White House between Trump, members of his Cabinet and a handful of oil executives, there remain a number of questions about how any of this will work, such as who would control the proceeds, how much say the Venezuelan government would have, and what the visibility into the entire process would look like.

“Right now, the private sector has nothing official to go on to have any sort of assurance, or any sort of confidence that whatever is going to happen, how is it going to be authorized based on US sanctions,” said Roxanna Vigil, who served as a senior sanctions policy advisor at the Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control.

“My biggest concern related to all of this is how are the Venezuelan people going to benefit?” said Vigil. “Because the most vulnerable player in all of this and the one that so far has had the least say is the Venezuelan people.”

Within the administration, the push to manage the immediate aftermath of Maduro’s ouster has masked another looming problem: Despite Trump’s insistence that US oil companies would pour into Venezuela, officials have no ready plan for convincing firms to invest hundreds of billions of dollars in rebuilding the nation’s energy infrastructure.

Wright held one-on-one meetings with oil executives on Wednesday after pitching the industry on Venezuela’s potential, which he said would require “tens of billions of dollars and significant time.” Trump is set to host the CEOs of several major energy companies at the White House Friday in a further effort to juice enthusiasm within the sector.

One energy lobbyist described frantic outreach from administration officials to the oil industry in recent days, starting with a flurry of calls on Monday aimed at fulfilling Trump’s assertion that companies would quickly pledge massive investments toward restoring Venezuela.

But those conversations have been largely one-sided, industry sources familiar with the discussions said.

The administration is “trying to sell us on engaging and getting in,” the energy lobbyist said. “It’s, ‘Hey look what we did for you. Now step up.’”

That push has been met with trepidation in public and even deeper skepticism in private, the industry sources said, driven by doubts that Trump can provide the stability and security needed for companies to set up operations — and that the potential profits will be worth the risk.

“Nobody wants to piss off Trump, but he’s put them in a difficult position,” said another energy lobbyist, noting that executives have been spooked by reports of government repression and roving militias in the aftermath of Maduro’s capture. “No company is going to say, I’ll invest $3 billion and I’ll go out and do the infrastructure without security.”

Those concerns have extended even to some within the Trump administration, where one official told CNN it wasn’t clear in the immediate hours after Maduro’s capture who was in charge of coming up with a plan for the oil production — even as Trump publicly promised massive new investments.

The official noted that before anything can happen, the United States will first have to ensure they can work with Rodriguez and her interim government. Wright and other officials in the meantime will have to develop a far more extensive sales pitch to convince companies to sign on to a project that some experts say could take a decade and $100 billion before it pays off in greater oil production.

The Department of Energy has conducted some analysis on what exactly would need to be done in Venezuela to rebuild the oil infrastructure, including on the nation’s energy grid.

But industry experts told CNN that the country needed both equipment and expertise, both of which have largely dried up since the former President Hugo Chavez nationalized the oil companies in 2007 and seized their assets.

“They all got screwed,” the administration official said of what, for many companies, was their last experience in Venezuela. “It’s not clear yet what we we’ll offer them to spend the billions needed to rebuild the infrastructure, and it’s clearly a risk.”