Long before festivals and film schools, Saad Nadim shaped how Egypt saw itself.

Long before documentaries gained prominence on festival circuits or in academic study, Saad Nadim was shaping the visual language through which Egypt recorded and interpreted itself. His camera moved between factory floors and Pharaonic temples, rural villages and moments of political upheaval, assembling a portrait of a country in transition and the human realities behind state-led progress.

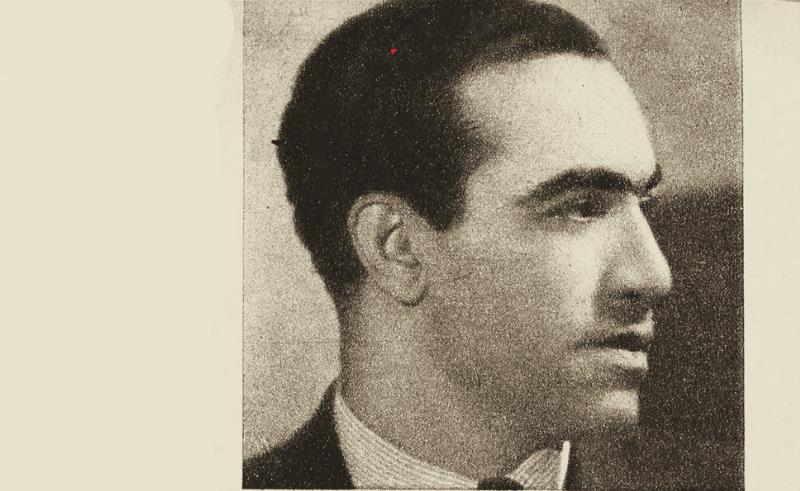

Born in Bulaq in the years surrounding the 1919 Revolution and named after nationalist leader Saad Zaghloul, Nadim grew up in a politically charged environment.

He was expelled from school for organising protests and later abandoned legal studies in favour of cinema, gravitating toward Studio Misr. There, under the mentorship of his cousin Salah Abu Seif, he trained as an editor and developed an early understanding of montage as a tool for shaping meaning from everyday images.

In 1950, a scholarship to the United Kingdom brought Nadim into contact with John Grierson, a central figure in the development of documentary cinema. The encounter reinforced his belief in film as a public service — a medium for education and social engagement. After returning to Egypt following the 1952 Revolution, he became a key figure in documenting the state’s modernisation projects and introduced the term al-film al-tasjīlī, helping establish documentary film as a distinct genre in Arabic cinema.

Over the course of more than eighty films, Nadim documented both infrastructure and community life. His work followed the construction of the Aswan High Dam, industrial labour in sugar and iron factories, Nubian daily life, and the temples of Philae prior to their relocation. His 1956 film Let the World Witness, which documented the Tripartite Aggression on Port Said, was distributed internationally in multiple languages, demonstrating the capacity of documentary film to operate as political testimony.

After leaving the Ministry of Culture due to bureaucratic pressures, Nadim shifted his focus to film criticism at the leftist newspaper Al-Masa, where his writing influenced public discourse and emerging filmmakers. In 1970, at the National Center for Documentary Films, he mentored a generation of directors including Daoud Abdel Sayed, Khairy Bishara, Atef Al-Tayeb, and Yehia El-Alamy, contributing to the rise of socially engaged Egyptian cinema.

Preservation remained central to his work into his final years. Despite declining health, Nadim continued overseeing documentation of Nubian villages and monuments, material that later circulated through UNESCO and was instrumental in recording threatened cultural heritage. As a director, editor, critic, mentor, and institutional builder, his contributions shaped the foundations of Egyptian documentary practice.

The current visibility of Egyptian and Arab documentary filmmaking is indebted to this legacy. Saad Nadim’s work established both a method and a vocabulary for nonfiction cinema in Egypt, positioning documentary film as a tool for observation, record, and public reflection.